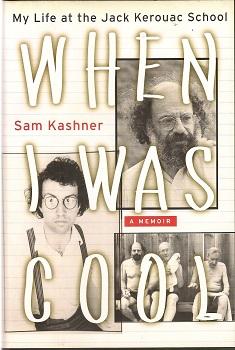

The following is from Sam Kashner’s book, When I Was Cool published in 2004. Sam had spend time with Allen and the “scene” in Naropa Institute and the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics during the years 1976-1978.

W. S. Merwin was a well-known poet, for what that’s worth in America, which means he still must feel pretty lonely—an ant crawling up an American anthill. It can be pretty discouraging.

Allen was fond of quoting Shelley about how poets were “the O unacknowledged legislators of the world.” I was discovering, however, that poets could be a pretty resentful bunch, possessors of bad attitudes. “Heap Big Jackasses,” Billy Jr. had said about the poets who came and went through the Jack Kerouac School.

The most sensitive poets seemed capable of cruelty, just like anybody else. And even when you think they should be sticking together, they stick out like a bunch of sore thumbs in the eye of the great American night. Geniuses and artists banding together—that was the idea behind the Kerouac School, though Allen was now starting to get a lot of criticism from the poets more acceptable to the academy, Merwin being one of them. Some said Allen was just using Naropa to find jobs for his friends. “What’s wrong with that?” Allen cried out when he heard that the National Endowment for the Arts had refused his application for money for the Kerouac School. “Do they want to punish me because my friends happen to be some of the greatest writers and poets of the twentieth century?” Allen seemed really perplexed. I couldn’t tell if he was asking me or telling me.

I tried to cheer him up with a Sam Goldwyn story that I had read about in Oscar Levant’s autobiography, Memoirs of an Amnesiac, a book that Jack Kerouac had loved, all about Levant’s famous breakdowns and his legendary nicotine habit and coffee drinking (up to fifty cups a day, like Voltaire). He was an addict of everything. “I’m going to hold my hand over my heart,” Kerouac used to say, “like Oscar Levant faking a heart attack.” The story was that lawyers hired by Sam Goldwyn told him that he couldn’t keep hiring his relatives for high positions at MGM because he would be accused of nepotism. “You mean they have a word for that?” Goldwyn had asked, incredulously.

Allen was in no mood for jokes. I’m not sure he even got it, any more than Sam Goldwyn had. All I knew was that this business with Rinpoche and W. S. Merwin had something to do with sex.

People wondered about Trungpa’s love life. Allen said you had to do what the teacher told you. That was part of crazy wisdom. He said that you had to trust the teaching.

Merwin had a beautiful girlfriend. The previous summer they had gone on a retreat with Rinpoche and other Buddhist practitioners. Merwin had requested permission to attend Rinpoche’s seminary, a kind of sleep-away camp for his most advanced students. Besides Allen and Peter, Merwin was the only other poet to have attended one of Rinpoche’s seminaries. Merwin had been to Naropa before, as Allen’s guest, but he was totally unfamiliar with Buddhist teachers, and his Hawaiian girlfriend, a woman named Dana Naone, knew even less. Trungpa evaluated applications to his seminaries like a college admissions officer. He apparently took great pleasure in turning people down. But Merwin’s application was approved, and for a $550 tuition fee he was invited to join the seminary, which would gather at a remote ski lodge in the Colorado Rockies.

Something apparently had happened between Merwin and Rinpoche at that retreat. Something had also happened between Dana Naone and Rinpoche. But what? Some people said that Rinpoche had wanted Merwin and his girlfriend to take off their clothes. One friend of Merwin’s said it was like Kristall- nacht. He said there was a lot of yelling and broken glass. He said it had nothing to do with crazy wisdom or the teachings,just that Rinpoche was just crazy and drunk with power. I heard that a lot when I came back to Naropa for the spring semester of 1977.

In the weeks following what was becoming known as “the Merwin incident,” the Kerouac School was in an anxious state. Mike Brownstein and Anne Waldman tried to deal with it by first asking Tom Clark what he thought he’d accomplish by publishing a story about something outsiders could never hope to understand. But the horse was not only out of the barn, it was off and running, setting records at Churchill Downs. And the barn? The barn was on fire. Something had to be done. While no one knew exactly what had happened to Merwin and Dana on that retreat, the intermezzo wasn’t pretty.

The spring and summer sessions wound to a close and I hung on in Boulder over the break, wondering whom they would get to replace Gregory. The fall semester passed without incident, and the spring term of my second and last year as a student was about to begin when Allen threw a party to welcome Ed Sanders to the Jack Kerouac School.

Allen had summoned Ed Sanders to Boulder to conduct an investigation into what had happened that night between W. S. Merwin and Trungpa Rinpoche. Allen didn’t have much choice. Reaction to Tom Clark’s story in the Boulder Monthly was yet threatening the Kerouac School’s very existence. Some people even thought that the bad publicity was making Rinpoche’s talks even weirder.

Meanwhile Allen informed me, now that I was a second-year student, that I had to start meditating or I wasn’t going to graduate. I got six credits just for showing up in the shrine room and taking off my shoes. It was less humiliating than dodge ball.

Rinpoche usually gave his talks wearing a beautiful blue suit. It shone in the light like the scales of a fish. Blue might have been Trungpa’s favorite color. He gave a talk called “The Blue Pancake.” It was about crazy wisdom. It was a Chicken Little story with a tantric twist. Rinpoche talked about the sky falling, about the moon and stars falling on your head. During the question-and- answer session someone asked Rinpoche why he was so enthusiastic about having the sky—the blue pancake—fall on everyone’s head. Rinpoche started to laugh. “I think it’s all a big joke, it’s a big message, ladies and gentlemen.” I didn’t get it.

I walked outside and looked up at the sky. The stars were still there. But I wasn’t sure about tomorrow, when I was supposed to join Ed Sanders’s official investigation into Rinpoche and the “Merwin incident.”

Allen said that I should follow Ed’s lead and pursue the investigation wherever it goes. He said to be careful, though, because other poets were already gunning for Rinpoche and for Allen, too. Their animosity went back to a public reading at the University of Colorado four years earlier. Gary Snyder, Robert Bly, and Allen were all giving a poetry reading to benefit Rinpoche’s Meditation Center. Trungpa was there, presiding as master of ceremonies. He was loaded on sake. He kept interrupting the poets; at one point he kept puffing up his cheeks and then collapsing them with his fists, making a kind of farting noise. Robert Bly was getting mad. Allen, who never really liked being upstaged, asked Rinpoche if this was all some kind of religious instruction. At the end of the evening Rinpoche apologized. Not for his behavior but for the poets. “I’m sure they didn’t mean what they said.” Then Rinpoche started to yell or possibly yodel, and he started banging on a large gong. Allen looked at him and pleaded with Trungpa to tell him if this was really him, or was he acting out of some Buddhist tradition.

“If you think I’m doing this because I’m drunk, you’re making a big mistake,” Rinpoche said, teetering on the edge of the stage at the school’s Macky Auditorium. One of the Vadjra guards reeled Trungpa back and prevented him from falling into the orchestra pit.

“Put it in the report,” Ed told the class.

All these unflattering stories. I think Allen believed that the report we were working on in Sanders’s class would ultimately absolve Rinpoche and thus Naropa from all suspicions of wrong action. But it wasn’t turning out that way. I worried that Allen was going to have a heart attack when he read the report, and that Anne would flay us alive and use our skins for a shawl.

In class, Sanders told us that the principle of “Investigative Poetics” was that “poetry should again assume responsibility for the description of history.” He said that we as young poets now had the chance to do this.

So we compiled a series of questions for Trungpa to respond to, but he refused to answer any of our questions when we presented them to him the next day. Through a spokesman, Rinpoche said that he would never cooperate with the class, and that this was the one class at the Kerouac School that was illegitimate. We then invited him to visit the Investigative Poetics workshop in a closed- door session. We took our job very seriously.

I wanted out of the class, but then Anne Waldman called me and said I should stay in and report back to her. Just what I wanted, to be Anne Waldman’s spy!

Some of Rinpoche’s closest students and advisers, members of the inner sanctum, wanted the investigation to stop. They said that the Buddhist community of Boulder should be on the lookout for what they called “the enemies of the dharma.” (Every single time I heard the word “dharma,” I thought of stuffed derma, the orangey- looking circle of fat that my grandmother loved to cook. It too had a lot of the teachings within it—just a different tradition—and anyway, Rinpoche always said that Jews made good Buddhists.)

In the midst of the investigation, Robert Bly returned to Boulder, ostensibly to give a poetry reading, but instead he tore into Rinpoche and into the very idea of the Kerouac School. Not surprisingly, he brought up Rinpoche’s fight with Merwin. He told the crowded room that the “Kerouac School is doomed.”

“Oh, God, not before accreditation,” I prayed to myself.

Someone in the audience yelled at Bly, called him a coward and a traitor to Shambhala. All these people started to seem crazy to me, caught up in some warfare that seemed more corporate than anything else. The next thing would be a proxy fight, or a hostile takeover of Naropa by the board of Yeshiva. I was getting mixed up. I think Allen was right. Bly and others saw an opportunity to stick it to Allen and Burroughs and their offspring, people that they never really liked anyway, and here was their big chance to say why.

The investigation dragged on through the spring semester. Merwin agreed to talk with us, and a few students who had actually attended the seminary retreat came forward. I met one of them at an all-night donut shop and took her testimony.

According to her account, it was like that Fatty Arbuckle party in the 1920s—Merwin was not an innocent, at least not at the beginning. He was a gentle guy, but he had tried to get into the spirit of the retreat. He was on the front lines of a terrific snowball fight earlier in the day with the Vadjra guards, and he had hatched a plan to create a little mischief by surprising Rinpoche with laughing gas, but they couldn’t get their hands on it—all the dentist offices were closed.

The events in question had occurred at the end of October, when leaves were turning and falling from the trees. All of a sudden it was Halloween, even in the Rocky Mountains. The last month of seminary is supposed to be the hardest. Cabin fever combined with crazy wisdom. The Vadjra guards were throwing a Halloween party: come as your neurosis. This would be the big blow-out before the transmission of some very heavy psychic petting, when the coal of the psyche, under enormous pressure and over time, is transformed into diamond.

Merwin and his companion, Dana, had arrived early at the party, according to my informant. They left early, too. Trungpa came late, and most people thought he was drunk. He was dressed casually in blue jeans and a lumberjack shirt. It was hot inside the ski lodge. It was noisy. It was turning into a typical Naropa party. Rinpoche decided to take off his clothes. He ordered a few of his most trusted guards to lift him up on their shoulders, like a bride at a Jewish wedding, only he was completely naked as they led him through the various rooms of the ski lodge. Everyone looked up. Rinpoche looked down. He noticed that Merwin and Dana were not there. He asked where they were. Someone said they had gone back to their rooms.

“Bring them down,” Trungpa said.

“They don’t want to come,” one of the guards told Rinpoche.

“Bring them anyway! Break down the door if you have to.”

But Merwin and Dana refused to open their door. One of the guards decided to smash the plate glass and enter the room. Merwin broke a beer bottle and held it out, threatening to cut anyone who came close to him or Dana. He thinks he might have even cut one or two guards simply by brandishing the broken bottle before throwing it against the wall and allowing himself to be dragged downstairs to the party, where Rinpoche was waiting

Downstairs, Trungpa urged all his students to expose their neuroses. Then he singled out Merwin and Dana, accusing them of indulging in neurotic violence and aggression. Merwin defended himself. He said that it was Trungpa who was being irresponsible and a traitor to the teachings. Merwin said that Rinpoche was cutting his own throat with the way he was going about teaching crazy wisdom.

Trungpa threw a glass of sake in Merwin’s face, then he turned to Dana Naone. “We’re both Oriental,” he told her. “The Communists ripped off my country. Only another Oriental can understand that.”

Dana then called Trungpa a Nazi.

That’s when Trungpa suggested that Merwin and Dana take their clothes off. After all, he, Rinpoche, was already naked. They turned him down.

When Ed Sanders, during the course of the investigation, spoke with Dana and introduced her evidence into the report, she told him how the Vadjra guards had dragged her off and threw her onto the floor. She could see Merwin struggling too a few feet away. She told Ed, “I fought back and called out to friends, men and women, whose faces I saw in the crowd, to call the police.” But no one did.

Only one man, Bill King, broke through the crowd, and while Dana was lying on the ground in front of Trungpa, King spoke up. “Leave her alone,” he said. “Stop it.” Then Trungpa got out of his chair and surprised Bill King with a punch from his good arm, which was quite strong, and knocked Bill King down, saying that no one else should interfere with what was going on. Another Vadjra guard Dana identified as Richard Assally was trying to pull her clothes off. She said that Trungpa leaned over and hit Assally in the head, urging him to “do it faster.” The rest of her clothes were torn off.

Merwin and Dana Naone stood in front of Rinpoche “like Adam and Eve,” as one eyewitness described it, and then Merwin spoke up. He challenged everyone else at the seminary to take off their clothes. Everyone did. Belt buckles fell to the floor, shoes were flipped in the air, people slithered out of their clothes like snakes in molting season. Then Rinpoche gave his final order of the evening: “Let’s dance.”

Someone put on a record, Roxy Music’s “Love Is the Drug.” Seeing their chance, Merwin and Dana grabbed their clothes and slipped away.

The next morning Rinpoche had a letter placed in everyone’s mailbox.

“You must offer your neuroses as a feast to celebrate your entrance into the Vadjra teachings. Those of you who wish to leave will not be given a refund [it had cost $550 to go to seminary], but your Karmic debt will continue as the vividness of your memory cannot be forgotten.”

I read the letter at the donut shop; it already had a few coffee

By the time Sanders left Boulder, he looked like an old man. He’d been through hell. He was living with Tom Clark and his family, who were trying not to answer the phone because threats were coming in. Tom wanted to publish the findings of the Investigative Poetry class in the Boulder Monthly, but Allen and Anne really didn’t want all of that to come out. The younger poets were angry with Tom that he would even think of doing that. But Tom had no allegiance to Rinpoche or to the Kerouac School. Tom liked Gregory’s way of doing things—keeping his distance within the circle. Sleeping with one eye open, even among his friends. I also got the feeling that there was no one Tom wouldn’t betray for a good story.

I saw Sanders the day Tom Clark took him to the airport. “Good-bye,” was the first thing I ever said to him. We shook hands. Ed was carrying a lot of the paperwork from our investigation in a big shopping bag. We were all a little frightened. Ed had told the class when we first started our investigation that when we opened the file on Rinpoche and Naropa, our first concern should be to define what he called “the area of darkness,” and to bring to that darkness “the hard light of Sophocles,” or something like that. But it was hard for us; these were our teachers, this was our school, and accreditation, we hoped, was just around the corner.

Just think of me, if you will, as I was then: an overheated imagination, a dangerously susceptible heart, a good-natured kid, maybe even a tender soul with a mind full of poesy, constantly in the presence of some of the flintiest (Burroughs pere), moodiest (Allen), and chilliest (see Waldman, Anne) temperaments around.

Ed’s report and the anxiety it was causing Allen put me in a state of despair that seemed only to induce a kind of narcolepsy. I slept like I was still growing. My somber fits had me (when I was awake)

playing lots of Bob Dylan records. Playing “Sad-eyed Lady of the Lowlands” more than once a day was a sure sign of my misery. ^ Even when I stepped into a restaurant, the one thing I always loved to do whatever my mood, I felt lost and alone.

I suppose that the reason I was eating myself alive was Ed’s report and the unhappiness it was causing the Kerouac School. As my two years at the Kerouac School were drawing to a close, I had stopped calling people up. The investigation had made me slide backwards into shyness and found me returning to my old haunts like an innocent, pretending that I knew no one. I was tormented by the desire for company but unable to pick up the phone. If the Kerouac School had taught me anything, it was to think of my teachers as trusty confidantes, to turn up the radio at a party and climb into the Faigos’ hot tub with Allen and Peter and a few girls, even if they laughed when the steam made my eyeglasses fog over. I was able to throw my library card over the garden wall and be a primitive youth, at least in the backyard of a suburban house. Maybe I was worried about what was going to happen to me after I graduated. Would graduating from the Jack Kerouac School make me a poet? Would I start to publish? Would I stay on in Boulder or go back to Merrick? I didn’t have a clue.

Yet I knew how upset Allen was, and I was afraid that somehow I had displeased him. Around Allen and Bill, even after all this time, I still felt like a schoolboy. Their every word sounded like it was coming from under a dome of gold, even if it was just Allen exasperated with Peter for putting his dirty underwear back in the drawer.

After a few weeks into my slough of despond, I finally screwed up my courage and called Allen. He told me he had just been to New York to accept an award for his poetry; he was now getting serious

attention from more academic poetry circles. I think he liked it. He had a habit of surrounding himself with poets who were never that good. Gregory noticed this right away, how Allen often championed the work of vastly inferior poets, some of them just because they were working-class guys who reminded him of Jack Kerouac. They were solidly built and had hair. “That’s not enough,” Gregory said, “to let them into Parnassus.” (I loved how he said “Parnassus” in that thick New York accent.)

Toward the end of the spring semester, Allen invited me to a party. He said we should talk about Ed’s investigation and what else Tom Clark planned to do to ruin the Kerouac School. I went with Allen. It was in a student apartment full of lots of kids trying to act grown up. Almost immediately they began asking questions. “Was it true about Rinpoche and what happened?”

Allen patiently explained to them that the so-called Merwin incident had indeed happened, but that things like individual rights didn’t really exist in a situation like that. He surprised me a little by saying that Merwin got what he’d deserved by going there in the first place.

I could tell Allen was getting angry. He said that Trungpa was a revolutionary, in that he was in some sense challenging the foundations of American democracy, and that, anyway, democracy was a failed experiment—the atom bomb proved that. “What Trungpa was up to was a new experiment in monarchy,” he said.

I saw Tom Clark at the party. He was listening to Allen, who didn’t notice him right away. Tom approached Allen, and it looked like they still might be friends. Tom asked Allen if he would be willing to do an interview about the Merwin problem, about religion and poetry. Allen didn’t want to do it. Clark had interviewed Allen once before for The Paris Review, an historic interview in fact. Allen wasn’t shy but he didn’t want to be interviewed for the Boulder Monthly; he wanted his interview in a more respectable forum, like Playboy.

That spring semester I had taken a class Allen was teaching on the prophetic books of Blake: The Book of Urizen, Jerusalem. A few days after the party, we left class on a night that felt like1 Yom Kippur. We

walked out into the cool mountain air. Tom Clark was waiting. He ® told Allen that the interview had to be now. People wanted to hear from Allen Ginsberg on the Kerouac School’s first big scandal. Allen agreed, and we walked back to Allen’s house on Mapleton.

Sometimes, despite his quiet, reasonable tone of voice, his sane manner, Allen could say some very outrageous things. That was a source of his power—his quiet mania, his well-mannered, apocalyptic thinking.

“I accuse myself all the time of seducing the entire poetry scene, and Merwin, into this impossible submission to some spiritual dictatorship, which they’ll never get out of again, and which will ruin American culture forever,” he said into Tom’s tape recorder. ‘Anything might happen. We might get taken over and eaten by the Tibetan monsters . . . All the horrific hallucinations of the Tibetan Book of the Dead are going to come true right now. Right here in Boulder . . . But with Trungpa . . . you’re talking about my love life. My extremely delicate love life, my relations with my teacher. Trungpa said that he was trying to explain to Dana that she should respect her roots by taking part in a classical experience. What he finally told me was, ‘This is an opportunity to turn poison into nectar.’ I don’t know what happened,” Allen admitted. “So I went to see Trungpa. It didn’t bother me too much, but apparently it bugged a lot of other people.”

Allen interrupted the interview to ask Peter to sing a little less loudly while he washed dishes. Julius kept switching a bouquet of flowers from one vase to another; he couldn’t quite decide which one “was a better house for the flowers.”

Allen then said he thought that Trungpa was being influenced by the teachers at the Kerouac School. Allen said Trungpa had sounded like a character from a Burroughs novel when he’d told

Dana, “You Oriental slick cunt, why are you hanging around with this honky?” Allen told Tom that he was “looking at it sort of as ® Burroughs-type humor,” rather than as anything truly sinister.

It seemed pretty sinister to me. I cringed when I heard Allen sounding like Burroughs.

“Everybody was getting very self-righteous,” Allen said, “for Rinpoche to bring up the fact that Dana was hanging around with a white guy. You’re not supposed to say things like that. Even if you’re a Vajrayana teacher, breaking down all privacy and breaking every possible icon in every mental form, and acting like a poet, no less. I mean you’re supposed to out-Gregory Gregory Corso, and out-Burroughs William Burroughs, if you’re a Vajrayana teacher.”

For Allen the whole incident was like the story of the snake and the rope, where you see a snake coiled up in a basket and, when you look closely at it, it turns out to be a rope. In other words, the entire world is an illusion.

It was getting late. That wasn’t an illusion. The kitchen was filling up with students. I tried my best to hide my feelings, but I thought that Allen couldn’t win, that we should be making ourselves as inconspicuous as possible. I mean, in a few days our parents would be here for Parents Weekend; didn’t we want them to approve of everything?

Tom’s being in Allen’s house and Peter’s brother walking like a zombie between Allen and Tom and the tape recorder weren’t helping Allen’s mood. Every one of Clark’s questions seemed to go against Allen’s grain. The whole issue was becoming about as friendly as a hangnail. Allen looked exhausted, but he was incapable of kicking people out. Even more people came into the house, and soon it was overflowing as students and hangers-on gathered in the kitchen, the living room, out on the porch, in the backyard. Allen became more and more angry, as if all the people in the house were feeding off the problem at hand.

It’s hard work, I thought, standing up to Clark’s questions, his wise-guy remarks, steeped in vinegar, that came flying through the air even over the head of the innocent. Allen said that Merwin had been free to leave and free to stay. Rinpoche put himself in danger by having an inexperienced meditator like Merwin even come into a situation like that. The worst thing Allen could say about Trungpa was that he had put Allen into a situation where he had to go through all this tsouris.

“As if I hadn’t had enough with LSD and fag liberation, now I’ve got to go through Vajrayana! And Merwin, whose poetry I don’t care about anyway! With Ed Sanders freaking out and saying it’s another Manson case! Ed has a large quotient of paranoia,” Allen explained to Tom’s tape recorder. “He’s been studying black magic and Aleister Crowley and playing around with all that. I mean, getting into the Manson thing, and then getting into Vajrayana and Trungpa and Merwin, is just made for Ed Sanders.

—————————————

February 19, 1995

A Poet of Their Own

By DINITIA SMITH

![]() ‘d got lost looking for W. S. Merwin’s house on the Hawaiian island of Maui, driving along roads lined with palms and sugar cane, then turning into a dense area of ironwood and heliconia trees. It was almost like rain forest here — pink and red hibiscus, ginger flowers filled with rain from the night.

‘d got lost looking for W. S. Merwin’s house on the Hawaiian island of Maui, driving along roads lined with palms and sugar cane, then turning into a dense area of ironwood and heliconia trees. It was almost like rain forest here — pink and red hibiscus, ginger flowers filled with rain from the night.

Then, suddenly, there he was, as if he’d somehow materialized out of the rain. He was standing by the gate to his land, looking like a Zen sensei, in a kimonolike shirt. He had slanting blue eyes and wide cheekbones. His skin was a silvery color. He was staring at me intently. “You said you’d be here at 10:15,” he said in a precise voice.

I had come to see Merwin because he had just won the $100,000 Tanning Prize. And I had the distinct impression he was not sure he wanted to be found.

For 18 years Merwin, now 67, has been living in this remote section of Hawaii, obsessively restoring, inch by inch, an abandoned pineapple farm to its original rain-forest-like state.

In Merwin’s poetry, the subject is loss, loss of place especially, the destruction of the environment:

Well they’d made up their minds to be every

where because why not.

Everywhere was theirs because they thought so.

They with two leaves they whom the birds despise.

In the middle of stones they made up their minds.

They started to cut.

When the Academy of American Poets announced it was giving Merwin the Tanning Prize, some said Merwin’s best work was behind him, that since his 1967 book, “The Lice,” a gloomy volume about the destruction of nature, his work had become obscure and abstract. (The critic Helen Vendler once called Merwin “a lesser Eliot,” and his poems “elusive pallors.”) In addition, Merwin is a chancellor of the academy; the judges — the late James Merrill, J. D. McClatchy and Carolyn Kizer — were all friends of Merwin’s.

Initially, Kizer wanted the prize to go to Gwendolyn Brooks, an African-American. “My qualm was it would look like the white male establishment handing around prizes to each other.” But James Merrill was chairman of the jury. “We wanted to find a real master,” he said last fall. “Gwendolyn Brooks would be very distinguished. But somehow I don’t think she’s a master.” Kizer, herself a potential candidate for chancellor, was outnumbered and eventually voted with the rest. “I revere him,” says Kizer. “Thank God it was Merwin, who has such enormous stature.”

Merwin — his first name is William, he doesn’t like Bill — tries to stay out of literary politics. He would like to be left alone to tend his garden and to write. He never answers his phone. Yet he’s ambivalent about solitude. “He’s a strange combination of recluse and very convivial,” says his wife, Paula. Merwin is always being torn away — especially to receive prizes. A few weeks after he won the Tanning, he flew to New York to get the $10,000 Lenore Marshall Prize. And then a few weeks after that he flew back again to receive a $105,000 Lila Wallace-Readers’ Digest Fellowship, awarded over a period of three years.

A Merwin poem is a highly crafted thing. The images seem etched; sometimes they come together with an almost magnetic force. He doesn’t use punctuation anymore, and often begins a sentence on the preceding line. His poetry has an onrushing, murmurous quality:

This is what I have heard

at last the wind in December

lashing the old trees with rain

unseen rain racing along the tiles

under the moon

wind rising and falling

wind with many clouds

trees in the night wind

“Everything’s got to do with listening,” Merwin says. We are sitting on the porch of his house. The house, small and quite dark, is built on the lip of a dormant volcano, Haleakala, that rises 10,000 feet above the sea.

“Poetry is physical. As Pound said, poetry has one pole in reason and one pole in music. It’s like making a joke. If you get one word wrong at the end of a joke, you’ve lost the whole thing.”

Merwin admits his work is sometimes abstract. “The word Lowell used was ‘history.’ I had great difficulty putting the actual, ephemeral, phenomenal fact into a poem — because I was interested in the universality of it. It’s the way the fact is heard or seen that counts.”

Merwin puts a knife with honey on it on the table. “Watch,” he says. Two geckos climb from a hidden place in the eaves, and begin licking the knife with pink tongues.

As Merwin and I talk, sudden, tropical rains come and go. The sun shines, then there’s a giant rainbow out over the Pacific. Under the table, Merwin’s four chows nap, their doggy smell filling the air. The chows are Merwin’s substitute for children. He carries photos of them in his wallet. “I’ve never had a desire for children,” he says. “I’m very sort of egotistical and impatient.”

Merwin is a curious mixture of sensuality and reserve. The epithet “pretty boy” has haunted him all his life. Time magazine once wrote that Merwin “flutters female hearts.” When he was younger, his face was almost faunlike — the eyes wary, trapped. Howard Moss, the late poetry editor of The New Yorker, used to keep a picture of Merwin on his wall. “Nobody has a right to be that good-looking,” he would say.

Over the years, Merwin has almost reinvented himself in the 19th-century Romantic ideal of the poet at one with nature. When he isn’t writing, he’s down in his forest, trying to restore it to its primeval state. In conversation, he refers constantly to “the environment,” to a tree that doesn’t belong in Hawaii but was brought here by merchants or missionaries, to a geothermal project on a neighboring island that he’s campaigning against. In many ways, Merwin’s is a mythic self, far from the little boy who grew up in a family clinging precariously to the middle class.

Merwin was the son of a Presbyterian minister in a poor parish in Scranton, Pa., surrounded by barren, strip-mined land. His mother had been orphaned as a child; then her brother died; then her first baby, Merwin’s older brother. Merwin grew up haunted by this brother, in an atmosphere permeated by grief. (He has a sister, Ruth, two years younger, a high-school teacher.)

Merwin’s father almost never spoke of his own family. The Merwins were rough people. Merwin’s grandfather was a drunken, violent riverboat pilot on the Allegheny. Merwin’s father had violence in him, too. He was “a bully,” says Merwin. “I was frightened of him. There was a fair amount of physical punishment. I turned on him physically two times in early adolescence. I thought one time he was getting abusive to my mother. When I was 13, I said, ‘Never touch me again!’ ” The theme of violence runs through Merwin’s poetry — violence to animals, to plants, to the soil, human violence. Merwin’s mother was a committed pacifist. Today, Merwin is a pacifist, too, and also a Buddhist. It’s as if Buddhism will somehow overcome the violence in the world — and the potential for violence within Merwin himself. Merwin’s father was also mean to pets — and to this day the sight of an animal being mistreated can send Merwin into a rage. “He has a temper,” says Merwin’s wife, “but he loses it very rarely. It’s always been on the occasion of somebody or something helpless.”

Merwin’s first poems were hymns he wrote for his father. And he is indebted to his father for a crucial lesson: “As long as you are doing something you respect, it’s O.K. not to make money,” is the way Merwin defines it. Today, Merwin lives on $25,000 to $30,000. With his resonant voice and dramatic pauses, Merwin is a riveting reader. “He could always just go to a university, stand up, open his mouth — and pick up $2,000,” says Moira Hodgson, a writer who lived with Merwin during the late 60’s. Unlike most poets, he doesn’t teach.

Merwin’s parents were uneducated, but Merwin is a translator of Neruda, “El Cid,” “The Chanson de Roland”; he reads and quotes often from Dante and the Welsh sagas. He was a scholarship student at Princeton in the 40’s — a waiter in one of the university’s elite eating clubs. “He was a kind of prodigy,” recalls Galway Kinnell, a Princeton classmate, “writing poetry that was so incredibly resonant.” Even then, Merwin attracted the attention of eminent older figures. He studied writing with the critic R. P. Blackmur, and showed his poems to Blackmur’s teaching assistant, John Berryman. Berryman, literally trembling with passion, would say, “You should get down on your knees to the Muse.” Sometimes Berryman told Merwin his poems were terrible, but he was encouraging too, in a “guarded” way. One day, Merwin asked how he could be sure his poetry was any good. Berryman’s response was memorable, and later, Merwin wrote a poem about it: “You can’t you can never be sure/you die without knowing.”

After Princeton, Merwin married Dorothy Jeanne Ferry, a secretary at Princeton. Merwin decided to write verse plays, and supported himself teaching the children of wealthy aristocrats. Eventually the poet Robert Graves hired him as a tutor to his son in Majorca.

Soon tension developed between Graves and Merwin. Graves was flirting outrageously with a house guest in front of his wife and children. “It was quite nauseating,” Merwin remembers. “He was treating her as though she were the Muse, flirting and not going to bed with her.” Merwin and Graves quarreled. Later, Merwin got back at Graves in a poem: “Opportunist, shrewd waster, half calculation,/Half difficult child; a phoney, it would seem.” Another Graves house guest was Dido Milroy, an Englishwoman with literary aspirations. Dido was a powerful figure, 15 years older than Merwin. They began to collaborate on a verse play. After Merwin left Majorca, he went to London, broke up with his wife, Dorothy, and eventually married Dido.

Merwin’s relationship with Dido dominated most of his adult life. She introduced him to English literary figures, helped get him a job translating “El Cid” for the BBC. Yet Dido was a devouring figure who wanted to inhabit Merwin’s very existence. “Dido’s ex-husband said she always wanted to own a poet,” says Merwin.

In 1952, Merwin published his first book, “A Mask for Janus.” The poems are ornate, sometimes mannered — and were good enough to win him the first prize an establishment poet must win, the Yale Younger Poets Prize, judged then by W. H. Auden.

Merwin felt confined by Dido and longed to hear American voices. In 1956, he won a fellowship at the Poets’ Theater in Boston and moved there. But Dido resolutely followed. In Boston, Merwin became part of a group who surrounded the charismatic, intermittently mad Robert Lowell, then teaching at Boston University. Lowell could be viciously competitive. One day, Lowell said to Merwin: “You’ll always be a good poet, but not a great poet.”

In Boston, Merwin abandoned verse plays. He had begun to rediscover his “American” voice and to explore his family’s secrets. His 1960 collection, “The Drunk in the Furnace,” is less precious than Merwin’s previous work, more in the American vernacular. The title poem is evocative of Merwin’s drunken grandfather:

They were afterwards astonished

To confirm, one morning, a twist of smoke like a pale

Resurrection, staggering out of its chewed hole,

And to remark then other tokens that someone

Cozily bolted behind the eye-holed iron

Door of the drafty burner, had there established

His bad castle.

Ever restless, the Merwins again moved back to England. In London, Merwin was friends with Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. Plath idolized Merwin — she wanted to be pure like him, free to just write. At one point, according to a memoir by Dido Merwin, Plath became infatuated with Merwin. But Merwin didn’t return her affections. The Merwins were witness to the awful disintegration of the Hugheses’ marriage before Plath’s suicide in 1963. Today, Merwin won’t talk about Plath. Plath is bad karma.

Finally, in 1968, Merwin separated from Dido (though she refused to give him a divorce). She clung to Merwin’s beloved house in Lacan, France, about which Merwin has written many poems and a prose collection, “The Lost Upland.”

Merwin began living part of the year in New York with Moira Hodgson, an English writer 20 years younger. Ever reluctant to let him go, Dido befriended Hodgson. “She had a very powerful personality,” says Hodgson. “It was a bit like the mother who says, ‘Let my son bring his girlfriends home.’ ” (Dido died in 1990.)

“Merwin was incredibly difficult,” adds Hodgson, “but all poets are incredibly difficult. He had a lot of conflicting feelings about leaving France, but he liked the excitement and hard edge of the city. Then he’d say, ‘O, God, I can’t bear to be here!’ “

Merwin opposed the Vietnam War. In 1971, when his book “The Carrier of Ladders” won the Pulitzer, he gave the $1,000 away to antiwar causes in protest.

On a reading trip to Hawaii in 1975, he met Dana Naone, a Hawaiian and an aspiring poet, also younger. “I think William was looking to chart a new course,” says Merwin’s friend the poet William Matthews. “Dana had a willingness to live in the country and get into the dirt.” Merwin and Hodgson broke up, and he began living with Naone.

One thing Naone and Merwin shared was an interest in Buddhism. Early in their relationship, they were invited to the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colo., a center for Buddhist studies where Allen Ginsberg was teaching.

Naropa was presided over by a Tibetan guru, Chogyam Trungpa, a tireless drunk and womanizer. At a Halloween party while Ginsberg was away, Trungpa ordered everyone to undress. Merwin and Naone refused. Trungpa’s bodyguards tried to batter down the door to their room. “I was not going to go peacefully,” Merwin recalls. “I started hitting people with beer bottles. It was a very violent scene.” Trungpa’s bodyguards stripped them, and the two figures cowered together before the guru like a chastened Adam and Eve.

The incident came to be mythologized as “The Great Naropa Poetry Wars.” Naropa became an epitaph for an era, a paradigm of the difference between two kinds of poetry — between Ginsberg’s passionate, declamatory style and Merwin’s restrained, Western formalism.

Despite what happened at Naropa, Merwin is still a Buddhist. He likes to quote the 13th-century Buddhist teacher Dogen, a contemporary of Dante’s: ” ‘You must let the body and mind fall away.’ ” In his house, Merwin has a zazen (meditation) room, a sparse place with four pillows, where he meditates — 45 minutes before breakfast, and again before dinner.

After Naropa, Merwin moved to Hawaii for good. He built his house with an inheritance from his mother. Later, he bought additional land with money left to him by George Kirstein, former publisher of The Nation. Eventually, he broke up with Dana Naone.

In 1970, Merwin met a blond woman who seemed to him “beautiful, terrified.” She was Paula Schwartz, an editor of children’s books. Schwartz was married, and they went their own ways. Then in 1982, Merwin (finally divorced from Dido) met Schwartz again at a dinner party in New York. In a poem, “Late Spring,” he describes the moment:

After looking and mistakes and forgetting

turning there thinking to find

no one except those I knew

finally I saw you

sitting in white

They were married in a Buddhist ceremony in 1983.

ONE AFTERNOON, IN THE RAIN, MERWIN takes me on a tour of the garden. “That’s a koa tree, what Hawaiian canoes were made from,” he says as we trudge along a wet, rocky path. “I put that in as a tiny tree.”

We come to an eroded ledge, one patch he hasn’t restored yet. “See there, that’s what it used to be like. It wants to be a forest!”

As he digs in the garden, Merwin thinks about poetry. Recently Milton’s sonnet about his wife came to mind: ” ‘Me thought I saw my late espoused saint/brought to me like Alcestis from the grave.’ “

“The fact is he never saw her,” says Merwin. “He was blind before he married her. It hadn’t occurred to me — his wife appears to him in a dream! I realized ‘Jove’s great son’ was Jesus, who rescues her from death.”

Since the restoration of Merwin’s land, since his marriage to Paula, his poetry has become more accessible, more celebratory. Now in his poems, you can almost feel the rain in the trees:

I lie listening to the black hour

before dawn and you are

still asleep beside me while

around us the trees full of night lean

hushed in their dream that bears

us up asleep and awake then I hear

drops falling one by one into

the sightless leaves

——————————————-

“The

perfect among the sages is identical with Me. There is

absolutely no difference between us”

Tripura

Rahasya,

Chap

XX, 128-133