My Ashram Story

by

by

Vishu Magee

![]() was asked to write my story of the founding and early years of the ashram.Here it is: no doubt it will run counter to the consensus view, and it may offend many of the faithful. I have no wish to be critical of either the ashram or its adherents. But critical thinking, so often missing in matters of religious belief, is always a good thing. I commend the ashram if indeed it is willing to publish this countervailing account.

was asked to write my story of the founding and early years of the ashram.Here it is: no doubt it will run counter to the consensus view, and it may offend many of the faithful. I have no wish to be critical of either the ashram or its adherents. But critical thinking, so often missing in matters of religious belief, is always a good thing. I commend the ashram if indeed it is willing to publish this countervailing account.

Naturally, mine is a personal narrative: after all, the ashram did happen at my home and under my watch. There were many co-founders, but it fell to me to be at the center of it all for the first ten years. I share my own struggles and mistakes from that time, as I share struggles and mistakes that we all made. I use very few names in order to avoid gossip, blame, or injury. That is a fire I do not wish to feed.

My story begins as a twenty-year-old in 1969, emerging from three years of intense self-exploration. I’d been working through a mountain of excruciating family-of-origin material, assisted only by LSD, a smattering of Buddhist works, and enough of an inner guide to keep me alive and on track. I’d managed to pull myself out of the morass and was beginning to seek the light – and that’s when I met Ram Dass.

Ram Dass was the first person I’d met who could offer the kind of guidance and hope I was looking for. Pyschedelics, the spiritual search, and the journey to India were all new territory – but Ram Dasswas older, he’d gone farther down a path that I was just entering – and he’d just returned from an epic encounter with Maharaj-ji in India. I saw the light and went for it, just like that. I know this happened to many of us.

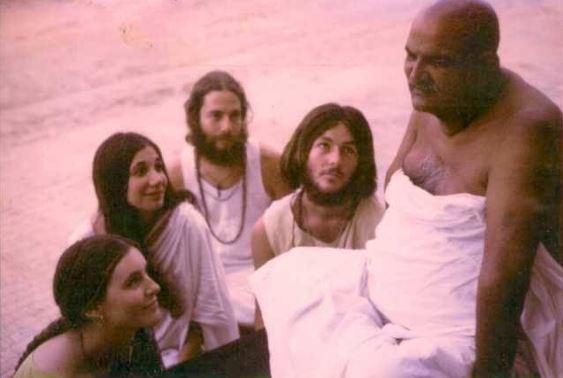

Within a year I finished Stanford and found myself on the road with Ram Dass and Swami Muktananda, awkwardly leading kirtan at evening events, working the retreats, spending all-day every-day with the crew. This was exactly what I wanted! Just a few months later I joined Ram Dass and about a dozen kids like me in India, sitting at the feet of Maharaj-ji.

There is no describing what it was like to be with Maharaj-ji. But I can say this with certainty: I desperately needed to feel like my quest was over and I’d come home –check! I wanted an all-knowing, loving, godlike guru who would take me as his disciple – check! I wanted a teacher who could answer the Big Question, “What’s going on here, anyway?” Check again! Or so I thought.

Maharaj-ji seemed to know everything about my past, my inner life, and my path forward. I melted in his love, was shattered by his gruffness, reveled in his hilarious and outrageous antics, and wept in moments of sweet Suchness. I would do anything he told me to do. At times, I felt I touched my deepest self. It was everything I could ask for.

Maharaj-ji never talked to me interms of Hinduism, but instead met me where I lived: in nature, mountains, rivers; truth, kindness, honesty, solitude. I was someone who tended to keep to myself rather than embrace the group – so it was no surprise that he would send me off on solo trips to seek and learn from my own experiences.

And then there was Ram Dass. He was the lieutenant who got almost all of us to Maharaj-ji but increasingly became just the eldest one among many. He also turned out to be no less complicated and flawed than anyone else.The group’s intense sibling rivalry inevitably challenged his position. It must have been hard for Ram Dass. Things changed a lot when he returned to the US part way through my stay – now it was just me and Maharaj-ji, no intermediary.

As months went by, I needed Maharaj-ji less and less. At the end of a year, as I began to feel I’d been drinking at the well long enough, he kicked me out and sent me home. It was the most amazing year of my life, for which I remain deeply grateful. Did the Big Question get answered? Nope. It simply melted away, leaving me ready to live my life relatively unburdened.

That’s just the short version – a momentous year compressed into a few sentences. But I should add that along the way I got married, divorced and then remarried. If that sounds confusing, well, it was!

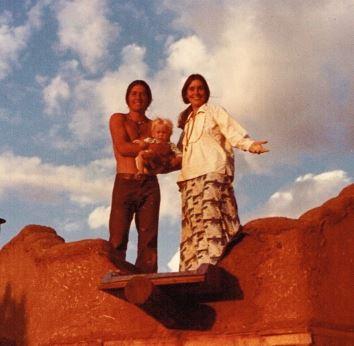

In 1973 Kausalya (Karen) and I settled in Taos, just a month before Maharaj-ji died. The rest of the group, now three or four dozen, was clustered in places like Berkeley, Boulder and Cambridge. But I had deep New Mexico roots and a preference for nature and solitude. Taos suited me just fine.

We did, however, get lonely. When everyone gathered in New York to be with Joya, we, afraid of missing out, headed east. I think most of us were still struggling to fill the void left by Maharaj-ji’s death. But Joya was a bust, and Kausalya and I soon left.

It was just a couple of years later (in ‘78) that we heard that Ram Dass had commissioned the sculpting of a Hanuman statue and was suggesting that we all get together to check it out and decide what to do with it. Kausalya and I wasted little time inviting everyone to Taos – we had land, a house, a stream, and tipis and tents we could borrow. Maybe some of the gang would even like Taos and choose to return!

We made preparations, and about forty people showed up, most of them old friends from the India days. Ram Dass, of course, was there. The statue was pulled from San Francisco in a U-Haul. We slid them a ngo wood box onto my construction trailer, which I positioned so that, at the unveiling, Hanuman would be framed by El Salto Peak with its sacred springs and waterfalls.

It was huge fun to be together again, camping on the land, cooking, and hanging out. We were so excited to open the crate! We struggled to remove the nuts and bolts, but finally pulled off the top. It was a wild scene – one of the guys had taken acid for the event, and he somehow lost his lungi (sarong) while yanking out handfuls of confetti. Problem was, he wore no undies, presenting a full moon and more! Classic!

Nevertheless, we succeeded in removing the front panel, and there was the statue: 1,600 pounds of gaudily painted marble. I was horrified – to my eye, attuned to Native American ways, it seemed so out of place against the backdrop of the mountain.

Others responded differently. One well-prepared group approached with a tray bearing a ghee lamp, incense, and flowers – ringing a bell and breaking into the arti song of worship we’d learned at the temples in India. No sooner did they do that than another contingent cried “No, no!” – defending the traditional view that worship of a murti should not be performed until the proper consecration ceremony is conducted by a brahmin priest.

Utter chaos threatened! But bye-and-bye everyone sat in a circle and we began to discuss ideas for building a temple, mostly in pie-in-the-sky places like Mt. Shasta. There were lots of people, lots of strong egos, and differing viewpoints and agendas. Lots of seeds got planted, many of which sprouted, for better or worse, over the ensuing years.

It was fascinating, and also a bit goofy. John Nichols, the Taos novelist, watched from a distance and later spoofed us in Nirvana Blues, in which he conjures up people in gorilla masks and King Kong t-shirts cruising Taos on motorcycles, while nearby a temple is being built by a young drug dealing couple with two kids. Milagro Beanfield War had nothing on us!

Ram Das sseemed sincere in offering the statue to the group, whileKausalya and I offered up our mountain paradise if the group wanted to buy us out. Fractious as always, we couldn’t decide what to do. But one thing was clear: we wanted a place we could call our own, and where we could come individually or as a group to remember Maharaj-ji and rekindle the magic.

I was asked to safeguard the statue for the time being; a committee was tasked with finding a good temple location; and everyone went home, leaving me with a monkey on my back.

This went on for two more Septembers, during which time Kausalya and I sold our mountain home and bought an old farm in the valley – an amazing find: 19 acres just five minutes’ walk from Taos plaza! It had a small adobe house built in 1934, and a sweet adobe barn consisting of three 20’x20’ spaces. I earmarked the old milk room as a workshop, leaving the chicken coop and hay spaces for other work on the land.

By now the search for the perfect temple spot had pretty much petered out, and at the ‘81 bhandara the satsang asked me if I’d be willing to take Hanuman out of his box and place him in the milkroom. I was not into this at all (bye-bye, woodshop), but I agreed – with conditions. I promised to keep the room locked except for visitors, but I would not perform devotional duties. If I was ambivalent, at least I was clear about it.

It turned out that the statue did need protecting. Someone alerted us to a planned heist, engineered by none other than Joya.That night I parked my truck against the milkroom door, set the parking brake, and locked it. We learned later that the would-be thieves actually came during the night but were deterred. Many was the time that I regretted having barricaded that door!

The simple truth was that I just wasn’t into the murti thing. But I did like being at the center of the group – for me, the need for membership, recognition and, yes, power within the satsang was the hook .I was not alone in this regard.

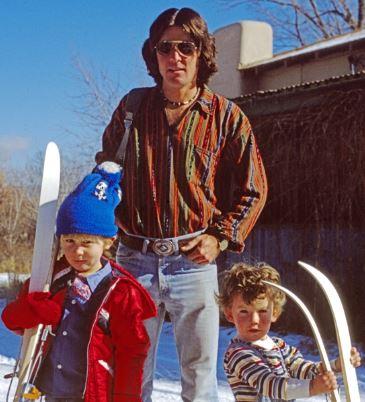

During this time Kausalya and I separated and divorced – amicably, despite considerable confusion. I had our two boys Jed and Aaron most of the time, and I worked in construction, but I was more or less a free agent. That was a good thing, because at the ‘82 bhandara a few of the guys took me aside and proposed to keep Hanuman here permanently, making my home our satsang retreat.

That was a shocker, and of course it raised all sorts of issues: of ownership, of roles and goals, finances, decision making, and overall management. But it was easy for a handful of friends to cook up an ad hoc agreement. I would draw up plans for finishing out the building with bathrooms, a kitchen, and guest quarters. They’d come up with the money and my basic living expenses would be covered, thus freeing me to work fulltime on the project. Day-to-day decision making and management would be entirely up to me. I went for it.

I had already moved into a more active role in the temple room. One or two Taos people wanted to come on Tuesday evenings to sing Hanuman chalisas – but I was the only one who knew the Chalisa by heart, so I led the singing. I’d always liked singing and drumming, and I was no stranger to devotional practice. The group began to grow, and Tuesday night became a regular kirtan. Daytime visitors increased as well, and some began to contribute time gardening or maintaining the temple and the murti.

My job description was: designer, builder, pujari, kirtan walla, cook, gardener, community relations, bookkeeper, business manager, greeter – and bouncer. Me, the introspective, solitude-loving outsider, now totally immersed! I got right into it, resolving to remember the name of every visitor, attend to their needs, and create a beautiful, safe and open space. As far as I was concerned, my job was an expression of gratitude to Maharaj-ji and his teaching, and I was determined to do it impeccably – even in those monkey matters about which I remained ambivalent. I drew the line at my front door, however. I knew myself and my need for my own space.

The ashram developed organically and remarkably smoothly, although it was curious that the majority of our old India crowd was not showing up. The successful ones were perhaps absorbed by their careers and families. But some, I knew, had simply detached from the group entirely. The ones with the strongest connections to Ram Dass showed up the most, and also carried a lot of the financial burden. I myself was enjoying working on the project with him.

Money became a thorny issue. Although there seemed to be plenty of it emanating from what we called the “family business,” we felt we needed to protect the investment. Ram Dass and others had plenty of non-profit experience, and all signs pointed to incorporating for purposes of fundraising, insurance, and the like. But first we had to secure our place in the neighborhood by getting a Special Use Permit from the Town – as a church.

This was a threshold moment, the implications of which completely escaped us at the time. First of all, it was a huge leap to go from a small, ad hoc, privately-held retreat to a public non-profit with fiduciary responsibilities and accountability. Second, it was no less portentous to become a church, implying a religious mission far more formal than anything we’d ever intended. Third, the Special Use Permit entailed getting permission from the neighbors – this we obtained, based on my personal promise to respect their needs by adequately managing crowds, traffic, noise and general behavior. (Here I admit to having fudged a bit – entirely unpardonable.)

It’s amazing that the neighbors, almost all of them traditional, Hispanic Catholics and survivors of the hippie invasion of the 60’s, went along with this monkey business. But they thought it was cool, and our little milkroom mandir was not so different from their small neighborhood capillos. They were perfectly OK with one annual blowout party – awesome neighbors!

In retrospect, it might have been better to pull up stakes and move to a more rural setting with fewer constraints. As it was, the permit was issued in ‘84 and we incorporated in ’86 as a not-for-profit church. The official name was “Neem Karoli Baba Ashram,” but the sign at the cattleguard read, “Neem Karoli Baba Ashram and Hanuman Temple.”

Money flowed in and the barn build-out progressed. Building is always a galvanizing process – it was tons of fun and I made new and lasting friendships. On kirtan nights the room was bursting at the seams, and the bhandara crowds approached 1,000. I could no longer keep up with all this and was grateful for all those who stepped up as cooks, gardeners, and kirtan singers.

Rarely did I have to be the bouncer. There were occasional wackos, like the guy who would show up stinking drunk and want to pick a fight. I actually threw Yogi Bhajan out once. First his armed guards refused to leave their rifles in the cars, and then he launched into a lecture on how we should run Maharaj-ji’s ashram. I wasn’t about to put up with that nonsense. (In contrast, Amritanandamayi was impeccably respectful, and we were happy to have her visit.)

I still struggled with the tug-of-war between Temple and Ashram, murti and Maharaj-ji, Hinduism and formless practice. In India Maharaj-ji had it set up this way: the temples were built by the roadside as a service to all comers, while the ashram was sequestered in the back and was basically open by invitation only. Passers-by could do their puja at the temples, oblivious to the resident baba, while Maharaj-ji insiders could hang with him and pretty much skip the temple aspect.He himself floated between the back quarters and the temple precinct.

But the milkroom in Taos was confusing. Maharaj-ji’s tucket was very understated – overwhelmed, in fact, by the size, color, accoutrements and fuss around the statue. Any newcomer was bound to get the impression that the place was all about Hanuman, which wasn’t correct. Our founding vision and mandate was for it to be about Maharaj-ji, with Hanuman being an optional element.

Moreover, celebrating Maharaj-ji required little formality, and absolutely nothing explicitly Hindu. Yet the jargon, the dress, the food, and the activity at the ashram was steadily becoming more culturally Indian and ritually Hindu, further conveying the impression of a Hindu temple.

I’m not saying this was bad – a lot of it was just nostalgia for the old India days. But it was sloppy. In my view, we needed to build a proper temple and produce a clean, architectural solution to the temple-ashram dichotomy. Besides which, the room was becoming too small for the crowds.

Nevertheless, I took a deep dive into temple activity. I led hundreds of hours of kirtan and Hanuman chalisas, got high as a kite on singing, and actually thought I saw tears course down Hanuman’s cheeks one giddy night. I led Shivratri singing dusk-to-dawn in ’85 without as much as a pee break – by midnight I was beginning to see a blue dot (a big deal in Siddha yoga). By dawn the dot was filling half my visual field, and by noon I was pretty much blind. The diagnosis was Harada’s disease, and the treatment was months of steroids. Back in the Kumaon hills, our old friend Tewari laughed and said I just hadn’t been able to handle all that shakti.

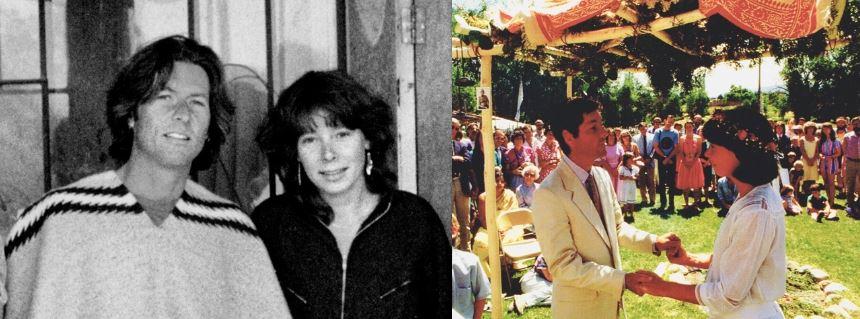

1984 was a big year for me. Nancy stepped into my life and everything changed. It was inevitable that we would someday leave to build a life for ourselves and our family, but in the short term she took on not just me, but Jed (10), Aaron (7) and the whole crazy ashram scene. We were deeply in love, and I felt so happy and complete.

We played in a jazz band, slipped away on wilderness trips, and in July of ’85 we had a big wedding right there in the temple garden. We built an aspen and wildflower chuppah, did the seven steps around the duni, and the Taos satsang honored us by cooking the entire wedding feast in the new kitchen. It was so sweet.

The push for a new temple got some wind in its sails when Ram Dass financed a working honeymoon trip to India for us. I was supposed to make the rounds of temples and elders, get in the right frame of mind to draw up a temple building – and Nancy and I were to enjoy a honeymoon break.

We did all that, and in the winter of ’86 I had drawings to present. Right away things got really interesting: contentiousness arose, initially over where to place the deities and the tucket. Sound familiar?

One view was that the temple space should be rather small, intended for just a handful of people at a time – whereas a bigger hall off to the side would house Maharaj-ji’s tucket and allow us to hang out and sing with less Hindu hoopla. Another view was to again have Hanuman and the tucket in the same space. But a new monkey wrench got thrown into the works when someone said “Why build a temple at all? Why not put our money and energy into service?”

Progress ground to a complete halt, and the debate got downright nasty. Older, wiser devotees absented themselves– and I was left to be the lightning rod. By the fall of ’86 I couldn’t bear it any longer. I took some Ecstasy late one night, sat down in the temple, and vowed to stay put until I found a solution. It came within an hour or two: yes, we should fulfill our obligation to build a temple, but we should do it in a village somewhere in India where people who otherwise could never afford either a murti or a temple could enjoy them and care for them.

In one fell swoop, we could honor our commitment, serve others, get the monkey off our back, downplay our complicated public profile, and return the ashram to the free and formless Maharaj-ji space we originally set out to create! I went home, caught some sleep, and in the morning I typed and copied onto pink paper a letter outlining my solution.

Everyone was shocked, and the result was perhaps predictable. A few friends fully supported the idea (108 roses appeared on Maharaj-ji’s tucket, wired from out of state), but most old-timers around the country either didn’t care or preferred to duck. The Taos satsang, most of whom had not been with Maharaj-ji, and for whom Hanuman was their main physical connection, dug in their heels.

And, of course, the idea fell completely flat with Ram Dass and his adherents.

Ram Dass happened to be in Santa Fe that day, so I drove to where he was staying and presented the letter. The look on his face was as if he’d stepped in a pile of poop – about what I expected. But he did allow that we should all get together and discuss the proposal.

My idea was doomed, and so was my tenure at the ashram. The recent contentiousness had taken its toll, and too many people with their own agendas wanted me out. Over the years it had been up to me to enforce basic rules. People didn’t like it when I clamped down on dope smoking, or when socializing and fun began to obscure the real purpose of the ashram. But that was part of the job.

I remember entering the temple one day to find that Hanuman was wearing sunglasses and a devotee was in the midst of installing dimmer switches. He explained that Hanuman had told him the lights were too bright and were hurting his eyes! I wasn’t about to let such goofiness go by: the sunglasses went, the lights returned to their former setting – but I was cast as the Bad Guy. These things add up over the years.

At some point in 1987 I announced my intention to leave. Nancy’s innate good sense was having its effect on me, and we were ready to have a normal life. After almost a decade, it was time for me to make money and build some sort of career. But the immediate reason was that I just wasn’t happy living at the ashram anymore.

Like me or resent me, the group wasn’t ready to replace me, and I agreed to stay on for a transitional period. We appointed an assistant Caretaker, and the democratization process (steering committee, etc.) stepped up its pace. There were a couple of excruciating big meetings to revisit the vision, the mission, and the goals – necessary, no doubt, but a far cry from the seat-of-the-pants, spirited founding back in 1981. No one was having much fun.

Our son Jake was born in January of 1988. The group was considerate in giving us space to care for a newborn. Nancy would bring Jake in for kirtan and chalisas, and he got used to being held by lots of people. But we needed to leave – the only question was when to go, and how to deal with selling our remaining holding to the group.

A few ashramites, bent on getting me out of there, made our decision easier by being unbelievably mean and nasty towards me. What was I doing, I asked myself, running this place for people who treated me so cruelly? It was just too much. In June of that year we moved to a nearby rental house, and soon we began building our current home in the foothills.

In the last thirty years I have seldom returned to the ashram. At first, I attended some kirtans, and I think I showed up at the next two bhandaras. But it felt awkward to be there, and from my new vantage point I didn’t like what I saw. My association with the place became an embarrassment.

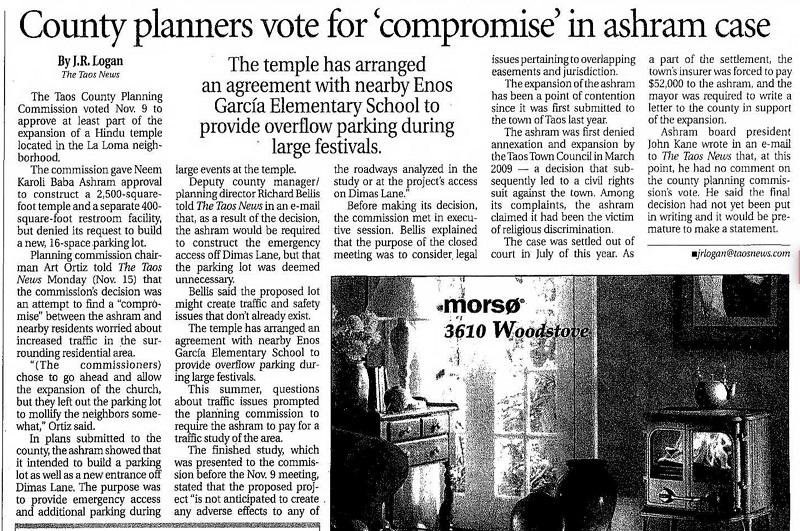

The neighbors liked what they saw even less, and some of them approached me in 2009 to talk about the ashram’s application for expansion. Their case was simple: since my departure, the ashram had neglected the interests of the neighborhood. Their list of grievances included traffic, noise, crowds, and disheveled weirdos cutting across their land to get to the ashram. How could expansion do anything but ruin their lives even more?

I was absolutely chagrined that the ashram had become such an aggravation to families who’d been there for generations. I had overpromised and underdelivered, and I apologized for my failure. The least I could do was speak on their behalf before the Town Council.

To date, the Town Planning Committee (a sensible and tolerant group) had recommended approving the ashram’s request. On this evening the Council was expected to vote in favor, despite the neighborhood protest. But eyes opened wide when I spoke in support of my old neighbors: if Vishu, the founder of the ashram, could oppose the permit, who were they to rule otherwise? The application was denied, 4-0.

Unbelievably, and in my view totally unconscionably, the ashram responded with a civil rights lawsuit accusing the Town of religious discrimination. Nothing could have been farther from the truth!

The Town, to avoid a nasty legal struggle, settled with the ashram for $52,000 and flipped the jurisdiction to the County, who approved the application. The ashram got its way, but I have to say this: with that lawsuit the ashram completely discredited itself as a carrier of Maharaj-ji’s teaching. This new temple is built on a lie.*

It’s been over thirty years since I left the ashram – and for me it has been a long process of unpeeling layer upon layer of the belief system I acquired since even before I met Ram Dass and journeyed to India.

Blind faith is a whole lot easier to take on than it is to take off: underlying each bit of magical thinking is some kind of need, some kind of hurt or fear, which gets unskillfully covered up by a chimerical, dharma dream. To undo it, the band-aids have to be ripped off one by one, the hurts properly attended to, and the needs addressed in healthy ways. It’s long, painstaking work. But nobody did this to me – I did it to myself. So, here’s to my undoing!

Closely related is the sense of entitlement that has often plagued the followers of Neem Karoli Baba – the feeling that we are somehow special and above the rules. In my life that has created problematic blind spots and behaviors which I have had to repair. In the case of the ashram, it enabled the appalling lawsuit which, too, must be repaired.

Skewer me with a trident if you want. But this is my story, and I am grateful for the opportunity to tell it.

Satya bol!

Vishu Magee

April 5, 2019

All rights reserved.

* Beezone editorial note

More on the lawsuit settlement (see Taos News article below) with the Town of Taos.

Neem Karoli Baba Ashram, Inc. v. Town of Taos

November 13, 2009

NEEM KAROLI BABA ASHRAM, INC., A NEW MEXICO NONPROFIT CORPORATION, PLAINTIFF,

v.

TOWN OF TAOS, A NEW MEXICO MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, AND RUDY ABEYTA, AMY QUINTANA, EUGENE SANCHEZ, AND MICHAEL SILVA, TOWN COUNCILORS, DEFENDANTS.

The Court will applied standards in considering Defendants’ motion. Plaintiff’s RLUIPA claim Plaintiff claims Defendants violated its members’ right to the free exercise of their religion under RLUIPA, 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc(a)(1), when it denied Plaintiff’s petition for the Town of Taos to annex Plaintiff’s land. Specifically, Plaintiff claims that by denying the petition for annexation, the Town Council’s Decision and Order imposed a substantial burden and undue burden on Plaintiff’s free exercise of religion in the absence of a compelling interest in violation of RLUIPA. The land use provision of RLUIPA prohibits discrimination and exclusion:

(1) Equal terms. No government shall impose or implement a land use regulation in a manner that treats a religious assembly or institution on less equal terms with a non-religious assembly or institution.

(2) Nondiscrimination. No government shall impose or implement a land use regulation that discriminates against any assembly or institution on the basis of religion or religious denomination.

(3) Exclusions and limits. No government shall impose or implement a land use regulation that —

(A) totally excludes religious assemblies from a jurisdiction; or

(B) unreasonably limits religious assemblies, institutions, or structures within a jurisdiction. 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc(a)(1) (emphasis added).

RULING: Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss should be Granted as to Plaintiff’s Second Count ((2) Nondiscrimination. No government shall impose or implement a land use regulation that discriminates against any assembly or institution on the basis of religion or religious denomination.) seeking a remedy under RLUIPA; it will be Denied as to all other counts.

The Town and Ashram’s Media News

Neem Karoli Baba Ashram and Hanuman Temple – History