Beezone Study

he Basket Of Tolerance is an essential gathering of traditional and modern literature, which I offer to all students and practitioners of the Way of the Heart (and all students of the traditions of mankind) as a useful and valuable resource for study of the historical traditions of human culture, practical self-discipline, religion, religious mysticism, “esoteric” Spirituality, and Transcendental Wisdom. I have selected, arranged, and commented upon the many books listed here, in order to provide a basic, inclusive, and comprehensive (but not overlong) representation (and Revelation) of the “Great Tradition” (or common Wisdom-Inheritance) of mankind.

he Basket Of Tolerance is an essential gathering of traditional and modern literature, which I offer to all students and practitioners of the Way of the Heart (and all students of the traditions of mankind) as a useful and valuable resource for study of the historical traditions of human culture, practical self-discipline, religion, religious mysticism, “esoteric” Spirituality, and Transcendental Wisdom. I have selected, arranged, and commented upon the many books listed here, in order to provide a basic, inclusive, and comprehensive (but not overlong) representation (and Revelation) of the “Great Tradition” (or common Wisdom-Inheritance) of mankind.

First on the list

Oration on the Dignity of Man

The following is a ‘study’ by Beezone of the pertinent parts of the book it feels are important for its own understanding of the man and the times in which he lived.

This ‘study’ is the BOLDing, paragraphing, and reduction of the text itself. Nothing else has been done to the text, it’s been reduced – trimmed.

***

ORATION ON THE DIGNITY

OF MAN

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

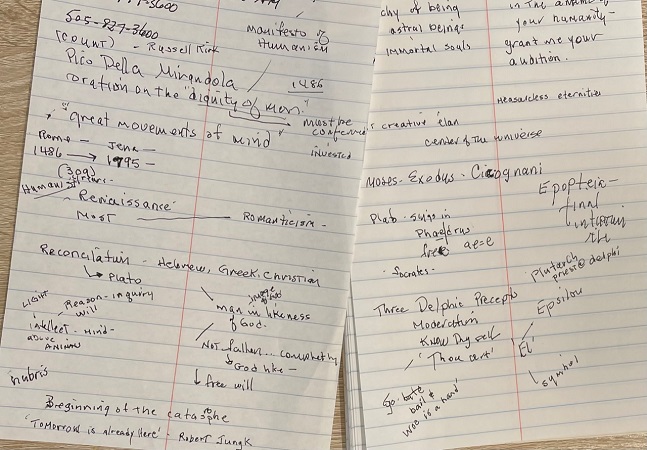

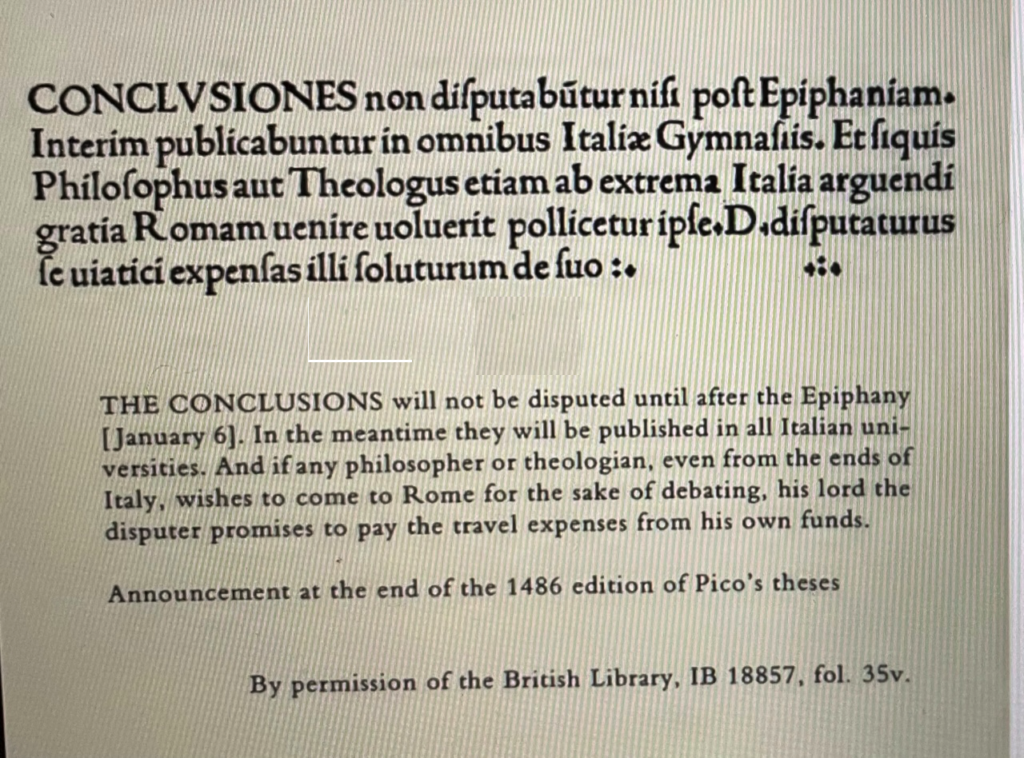

This ‘most elegant oration” (oratio elegantissima) as it was called in the first edition of the collected works and as it has been named ever since, of Giovanni Pico, Count of Mirandola (1463-1494) was composed as a prelusion to the disputation which Mirandola proposed to hold shortly after Epiphany, 1487. In this disputation, as he recounts in the course of the “Oration,” Pico proposed to defend nine hundred propositions.

The disputation did not take place because it was suspended by Pope Innocentius VIII, who also appointed a commission to examine the theses.

The Conclusiones were first published by Eucharius Silber in Rome on 7 December, 1486. The 24-year-old Pico planned to publicly “defend” his theses in Rome, in January 1487, before a commission of cardinals and theologians appointed by Pope Innocent VIII. However, thirteen of the 900 theses were judged heretical by Catholic theologians and the public defense was called off by the Pope and never took place.

Some of them were condemned as counter to the accepted teachings. In reply Pico composed an Apology, in the course of which he reproduced the second portion of the “Oratio” practically verbatim.

This is, consequently, the first appearance of the “Oratio,” or any part of it in public print. The whole of the “Oratio” was first published in the collection of Pico’s works edited and published by his relative, Gian Francesco Pico, in 1496. The qualifying phrase “on the dignity of man” is a later addition, but has become practically identical with the oration, even though some writers have protested that it has reference only to the first portion.

INTRODUCTION

“The enduring value of Pico’s work is due, not to his Quixotic quest of an accord between Pagan, Hebrew, and Christian traditions,” John Addington Symonds writes, “but to the noble spirit of confidence and humane sympathy with all great movements of the mind, which penetrates it.” Out of the bulk of the works of Count Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who challenged the doctors of the schools to dispute with him on nine hundred grave questions, the only production widely read nowadays is this brief discourse, “The Dignity of Man,” delivered by him in 1486, at Rome, when he was only twenty-four years old. The oration, which was his glove dashed down before authority, lives as the most succinct expression of the mind of the Renaissance.

Pico, a son of the princely house of Mirandola, one of the most brilliant of the great Renaissance families, studied at Bologna, and wandered through the Italian and French universities for seven years, becoming immensely erudite, proficient in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Chaldee, and Arabic. Mystic, magician, and grand scholar, he combined in his character the Gothic complexity of the Middle Ages with the egoism and enlightenment of the Renaissance. He was the most romantic of all the Humanists. His immense design it was to effect a synthesis and reconciliation of Hebrew, classical, and Christian traditions. No one did more than Pico to restore Plato to dignity in the schools; yet, as Symonds observes, “uncontrolled by critical insight, and paralyzed by the prestige attaching to antiquity, the Florentine school [which Pico and Ficino dominated] produced little better than an unintelligent eclecticism.” Among Pico’s nine hundred questions were some propositions which hung close upon the brink of heresy. He thought that the secrets of the magicians could prove the divinity of Christ, and that the Cabala of the medieval Jews would sustain the Christian mysteries. Thus, haranguing, reading, wandering, preaching, commencing a vast work against the enemies of Christianity, he spent his brief life, dying of a fever* before he was thirty—though he already had abjured the world and the flesh, and planned to wander barefoot as an evangelist.

*See – Poisoning of Pico della Mirandola

Now this eccentric genius’ “Dignity of Man” is the manifesto of humanism. Man regenerate—“this, visibly,” Egon Freidell says, “is the primary meaning of the Renaissance: the rebirth of man in the likeness of God.”

The man of the Middle Ages was humble, conscious almost always of his fallen and sinful nature, feeling himself a miserable foul creature watched by an angry God. Through Pride fell the angels.

But Pico and his brother-humanists declared that man was only a little lower than the angels, a being capable of descending to unclean depths, indeed, but also having it within his power to become godlike.

This is the theme of Pico’s oration, elaborated with all the pomp and confidence that characterized the rising Humanist teachers. “In this idea/’ continues Freidell, “there lay a colossal hybris unknown to the Middle Ages, but also a tremendous spiritual impulse such as only modem times can show.”

The very Cherubim and Seraphim (celestial beings) must endure the equality of man, if Man cultivates his intellectual faculty. It is the spirit, the spark of Godhood, which raises Man above all the rest of creation and makes him distinct in kind from all other living things. For all his glorification of Man, however, Pico has no touch of the modem notion that “man makes himself,” and that an honest God’s the noblest work of man. It is only because Man has been created in the image of God that Man is angelic. God, in his generosity, has said to Man, “We have made thee neither of heaven or of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, so that with freedom of choice and with honor, as though the maker and moulder of thyself, thou mayest fashion thyself in whatever shape thou shalt prefer. Thou shalt have the power to degenerate into the lower forms of life, which are brutish. Thou shalt have the power, out of thy soul’s judgment, to be reborn into the higher forms, which are divine.”

This, then, is the essence of humanism, which spread out of Italy unto the whole of Europe, reaching its culmination, perhaps, in Erasmus and Sir Thomas More. (More it was who translated the life of Pico by his nephew Giovanni Francisco into English.) God had given Man great powers, and with those powers, free will. Man might rightfully take pride in his higher nature, and turn his faculties to the praise and improvement of noble human nature. A world of wonder and discovery lay before the Renaissance humanist. Yet all this dignity of human nature was the gift of God: the spiritual and rational powers neglected—and through free will Man is all too able to neglect them—Man sinks to the level of the brutes.

The humanist does not seek to dethrone God: instead through the moral disciplines of humanitas, he aspires to struggle upward toward the Godhead.

Thus a degree of humility chastened the pride of even the most arrogant humanist of the Renaissance. But the seed of hubris, overweening self-confidence, was sown; and a time would come when Man would take himself for the be-all and end-all; and then Nemesis would be felt once more, and….The end, however, is not yet. It has remained for us of the twentieth century to look back upon the course of this hubris, diffused over all the world; and to see the oratorical aspirations of the humanists transformed into the technological aspirations of the modem sensual man; and to glimpse the beginning of the Catastrophe, perhaps, in a handful of dust over Hiroshima, or in the leaden domination of the Soviets, or in the pornography and hysteria of the corner news-stand. Robert Jungk, in Tomorrow Is Already Here, describes the stage of this progress at which we have arrived: “The stake is the throne of God.

To occupy God’s place, to repeat His deeds, to recreate and organize a manmade cosmos according to man-made laws of reason, foresight, and efficiency”—this is the ambition of the twentieth-century energumen of progress. And to gratify this ambition, we have moved very near to the dehumanization of Man. In our lust for divine power, we have forgotten human dignity.

By “the dignity of man,” Pico della Mirandola meant the high nobility of disciplined reason and imagination, human nature as redeemed by Christ, the uplifting of the truly human person through an exercise of soul and mind. He did not mean a technological or sensate triumph. “The dignity of man” is a phrase on the lips of all sorts of people nowadays, including Communist publicists; and by it, all sorts of people mean merely the gratification of the ego, the egalitarian claim that “one man is as good as another, or maybe a little better.”

Pico, however, knew that no being can dignify himself: dignity is a quality with which one is invested; it must be conferred. For human dignity to exist, there must be a Master who can raise Man above the brute creation. If that Master is denied, then dignity for Man is unattainable.

For despite all the cant concerning the dignity of man in our time, the real tendency of recent intellectual currents has been to sweep true human dignity down to a morass of mechanistic indignity. Joseph Wood Krutch, a generation ago, in his Modern Temper, described with a sombre resignation this process of degradation. Without God, Man cannot aspire to rank with Cherubim and Seraphim. Freud convinced the crowd of intellectuals that Man was nothing better than the slave of obscure and arrogant fleshly desires; Alfred Kinsey, unintentionally reducing to absurdity this denial of human dignity, advised his fellow-creatures to emulate, if not the ant, at least the snake—for Man, so the modern dogma goes, lives only to lust. In this fashion phrases Unger on in men’s mouths long after the object they describe has been forgot.

Pico della Mirandola, Platonist and Christian and sorcerer and rhetorician and mystic, designed his nine hundred questions as an irrefragable proof of Man’s uniqueness. Emerson echoed him, five centuries after:

There are two laws discrete Not reconciled,—

Law for man, and law for thing;

The last builds town and fleet, But it runs wild, And doth the man unking.

By a discipline of the reason and the will, to make Man kingly, even angelic—this was Pico’s hope, and it has been the hope of all true humanists after him. Thing, nevertheless, has run wild in our time, building town and fleet, bomb and satellite; and the Man has been unkinged; and human dignity is at its lowest ebb, now, when Man’s power over nature is at its summit. A real man, in any age, is dignified and nobly human in proportion as he akknowledges the overlordship of One greater than Man. If Things are to be thrust out of the saddle once more, and Man mounted (in Pico’s phrase) to “join battle as to the sound of a trumpet of war” on behalf of Man’s higher nature, then some of us must go barefoot through the world, like Pico, preaching against the vegetative and sensual errors of the time.

Russell Kirk

The Text

An Oration on the Dignity of Man

Most esteemed Fathers, I have read in the ancient writings of the Arabians that Abdala the Saracen* on being asked what, on this stage, so to say, of the world, seemed to him most evocative of wonder, replied that there was nothing to be seen more marvelous than man. And that celebrated exclamation of Hermes Trismegistus, “What a great miracle is man, Asclepius” confirms this opinion.

Saracen – was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Petraea and Arabia Deserta. The term’s meaning evolved during its history of usage. During the Early Middle Ages, the term came to be associated with the tribes of Arabia.

As I reflected upon the basis assigned for these estimations, I was not fully persuaded by the diverse reasons advanced by a variety of persons for the preeminence of human nature; for example: that man is the intermediary between creatures, that he is the familiar of the gods above him as he is lord of the beings beneath him; that, by the acuteness of his senses, the inquiry of his reason and the light of his intelligence, he is the interpreter of nature, set midway between the timeless unchanging and the flux of time; the living union (as the Persians say), the very marriage hymn of the world, and, by David’s testimony but little lower than the angels.

These reasons are all, without question, of great weight; nevertheless, they do not touch the principal reasons, those, that is to say, which justify man’s unique right to such unbounded admiration.

THE CALL

I asked, should we not admire the angels themselves and the beatific choirs more? At long last, however, I feel that I have come to some understanding of what is the most fortunate of living things and, consequently, deserving of all admiration; of what may be the condition in the hierarchy of beings assigned to him, which draws upon him the envy, not of the brutes alone, but of the astral beings and of the very intelligences which dwell beyond the confines of the world.

A thing surpassing belief and smiting the soul with wonder. Still, how could it be otherwise? For it is on this ground that man is, with complete justice, considered and called a great miracle and a being worthy of all admiration.

Hear then, oh Fathers, precisely what this condition of man is; and in the name of your humanity, grant me your benign audition as I pursue this theme. God the Father, the Mightest Architect, had already raised, according to the precepts of His hidden wisdom, this world we see, the cosmic dwelling of divinity, a temple most august. He had already adorned the supercelestial region with Intelligences, infused the heavenly globes with the life of immortal souls and set the fermenting dung-heap of the inferior world teeming with every form of animal life.

But when this work was done, the Divine Artificer still longed for some creature which might comprehend the meaning of so vast an achievement, which might be moved with love at its beauty and smitten with awe at its grandeur. When, consequently, all else had been completed (as both Moses and Timaeus testify), in the very last place, He bethought Himself of bringing forth man.

Pico’s man has not been created in the image of God, but is opus indiscretae imaginis, he does not have a pre-defined image. Both in the Oration and in the Symposion: a) we find praise of someone – Eros, and the human creature, respectively – not for his real dignity, based only on stereotypes and clichés, but for his potential capacity to reach the highest of ends; b) we find someone who is in an intermediate condition, neither mortal nor immortal, neither of the earth nor of the heavens, Symp. 203e; c) we find someone placed in the midst (medium, metaxù in the Symposion), capable of reaching, through the love of knowledge, the supreme reality, Symp. 202d; d)we find the priority of love, of desire, of the will as the final essence of the human being, while the intellectual element is not against but inside the spiritual development, supported by the dynamic of desire (and here there is again a parallel between the ascent described at the end of Diotima’s intervention and the exit from the cave described in theRepublic VII). Source

The Real War

For it is a patent thing, oh Fathers, that many forces strive within us, in grave, intestine warfare, worse than the civil wars of states. Equally clear is it that, if we are to overcome this warfare, if we are to achieve that peace which must establish us finally among the exalted of God, philosophy alone can compose and allay that strife.

In the first place, if our man seeks only truce with his enemies,

moral philosophy will restrain the unreasoning drives of the protean brute, the passionate violence and wrath of the lion within us. If, acting on wiser counsel, we should seek to secure an unbroken peace, moral philosophy will still be at hand to fulfill our desires abundantly; and having slain either beast, like sacrificed sows, it will establish an inviolable compact of peace between the flesh and the spirit.

Dialectic will compose the disorders of reason torn by anxiety and uncertainty amid the conflicting hordes of words and captious reasonings.

Natural philosophy will reduce the conflict of opinions and the endless debates which from every side vex, distract and lacerate the disturbed mind. It will compose this conflict, however, in such a manner as to remind us that nature, as Heraclitus wrote, is generated by war and for this reason is called by Homer, “strife.”

Natural philosophy, therefore, cannot assure us a true and unshakable peace. To bestow such peace is rather the privilege and office of the queen of the sciences, most holy theology.

Natural philosophy will at best point out the way to theology and even accompany us along the path, while theology, seeing us from afar hastening to draw close to her, will call out:

“Come to me you who are spent in labor and I will restore you; come to me and I will give you the peace which the world and nature cannot give.”

The Ladder – Union of Male and Female

This is the friendship which the Pythagoreans say is the purpose of all philosophy. This is the peace which God established in the high places of the heaven and which the angels, descending to earth, announced to men of good will, so that men, ascending through this peace to heaven, might become angels. This is the peace which we would wish for our friends, for our age, for every house into which we enter and for our own soul, that through this peace it may become the dwelling of God; so that, too, when the

- soul, by means of moral philosophy and

- dialectic shall have purged herself of her uncleanness,

- adorned herself with the many disciplines of philosophy as with the raiment of a prince’s court and

- crowned the pediments of her doors with the garlands of theology,

- The King of Glory may descend and, coming with the Father, take up his abode with her.

If she prove worthy of so great a guest, she will, through his boundless clemency, arrayed in the golden vesture of the many sciences as in a nuptial gown, receive him,

not as a guest merely,

but as a spouse.

And rather than be parted from him, she will prefer to leave her own people and her father’s house. Forgetful of her very self she will desire to die to herself in order to live in her spouse, in whose eyes the death of his saints is infinitely precious: I mean that death— if the very plenitude of life can be called death — whose meditation wise men have always held to be the special study of philosophy.

Justification – “Consider carefully and with full attention, Oh Fathers”

The dignity of the liberal arts, which I am about to discuss, and their value to us is attested not only by the Mosaic and Christian mysteries but also by the theologies of the most ancient times.

What else is to be understood by the stages through which the initiates must pass in the mysteries of the Greeks? These initiates, after being purified by the arts which we might call expiatory, moral philosophy and dialectic, were granted admission to the mysteries.

What could such admission mean but the interpretation of occult nature by means of philosophy? Only after they had been prepared in this way did they receive “Epopteia”* that is, the immediate vision of divine things by the light of theology. Who would not long to be admitted to such mysteries?

*Those who had attained épopteia (Greek: ἐποπτεία) (contemplation), who had learned the secrets of the greatest mysteries. lit. “Beholding”.

Who would not desire, putting all human concerns behind him, holding the goods of fortune in contempt and little minding the goods of the body, thus to become, while still a denizen of earth, a guest at the table of the gods, and, drunk with the nectar of eternity, receive, while still a mortal, the gift of immortality?

We shall be able to measure with the rod of indivisible eternity all things that are and that have been; and, grasping the primordial beauty of things, like the seers of Phoebus, we shall become the winged lovers of theology. And at last, smitten by the ineffable love as by a sting, and, like the Seraphim, born outside ourselves, filled with the godhead, we shall be, no longer ourselves, but the very One who made us.

Oh Fathers, we cannot fail to recall those three Delphic precepts which are so very necessary for everyone about to enter the most holy and august temple, not of the false, but of the true Apollo who illumines every soul as it enters this world.

That is: “Nothing too much,” duly prescribes a measure and rule for all the virtues through the concept of the “Mean” of which moral philosophy treats.

In like manner, that other aphorism, that is, “Know thyself,” invites and exhorts us to the study of the whole nature of which the nature of man is the connecting link and the “mixed potion”; for he who knows himself knows all things in himself, as Zoroaster first and after him Plato, in the Alcibiades, wrote.

Finally, enlightened by this knowledge, through the aid of natural philosophy, being already close to God, employing the theological salutation that is “Thou art,” we shall blissfully address the true Apollo on intimate terms.

Ancient Wisdom

These philosophers of the past all thought that nothing could profit them more in their search for wisdom than frequent participation in public disputation. Just as the powers of the body are made stronger through gymnastic, the powers of the mind grow in strength and vigor in this arena of learning.

But to speak from my own conscience, I might say with greater truth that there is nothing singular about me. I admit that I am devoted to study and eager in the pursuit of the good arts. Nevertheless, I do not assume nor arrogate to myself the title learned. If, consequently, I have taken such a great burden on my shoulders, it is not because I am ignorant of my own weaknesses. Rather, it is because I understand that in this kind of learned contest the real victory lies in being vanquished.

There is in each school some distinctive characteristic which it does not share with any other. To begin with the men of our own faith to whom philosophy came last, there is in

John Scotus both vigor and distinction, in

Thomas, solidity and sense of balance, in

Egidius, lucidity and precision, in

Francis, depth and acuteness, in

Albert, a sense for ultimate issues, all-embracing and grand, in

Henry, as it has seemed to me, always an element of sublimity which inspires reverence.

Among the Arabians, there is in

Averroes something solid and unshaken, in

Avempace, as in Al-Farabi, something serious and deeply meditated; in

Avicenna, something divine and platonic.

Among the Greeks philosophy was always brilliant and, among the earliest, even chaste: in

Simplicius it is rich and abundant, in

Themistius elegant and compendious, in Alexander, learned and self-consistent, in

Theophrastes, worked out with great reflection, in

Ammonius, smooth and pleasing. If you turn to the

Platonists, to mention but a few, you will, in

Porphyry, be delighted by the wealth of matter and by his preoccupation with many aspects of religion; in

Iamblicus, you will be awed by his knowledge of occult philosophy and the mysteries of the barbarian peoples; in

Boethius, among Latin writers, promised to compose such a harmony, but he never carried his proposal to completion.

St. Augustine also writes, in his Contra Academico that many others tried to prove the same thing, that is, that the philosophies of

Plato and Aristotle were identical, and by the most subtle arguments.

“I should wish to propose a new philosophy”

Nor ought anyone to be surprised, that in my early years, at a tender age at which I should hardly be permitted to read the writings of others (as some have insinuated) I should wish to propose a new philosophy. They ought rather to praise this new philosophy, if it is well defended, or reject it, if it is refuted.

NUMBERS

Finally, since it will be their task to judge my discoveries and my scholarship, they ought to look to the merit or demerit of these and not to the age of their author. I have, in addition, introduced a new method of philosophizing on the basis of numbers.

This method is, in fact, very old, for it was cultivated by the ancient theologians, by Pythagoras, in the first place, but also by Aglaophamos, Philolaus and Plato, as well as by the earliest Platonists; however, like other illustrious achievements of the past, it has through lack of interest on the part of succeeding generations, fallen into such desuetude, that hardly any vestiges of it are to be found.

MAGIC – The highest realization of natural philosophy.

I have also proposed certain theses concerning magic, in which I have indicated that magic has two forms.

One consists wholly in the operations and powers of demons, and this consequently appears to me, as God is my witness, an execrable and monstrous thing.

The other proves, when thoroughly investigated, to be nothing else but the highest realization of natural philosophy.

The Greeks noted both these forms. However, because they considered the first form wholly undeserving the name magic they called it, φύγε, goeteia, reserving the term μαγεία, mageia, to the second, and understanding by it the highest and most perfect wisdom.

The term, magus,

پرستنده ی الهی

in the Persian tongue, according to Porphyry, means the same as interpreter and “worshiper of the divine” in our language.

Moreover, Fathers, the disparity and dissimilarity between these arts is the greatest that can be imagined. Not the Christian religion alone, but all legal codes and every well-governed commonwealth execrates and condemns the first; the second, by contrast, is approved and embraced by all wise men and by all peoples solicitous of heavenly and divine things.

The first is the most deceitful of arts; the second, a higher and holier philosophy.

The former is vain and disappointing; the latter, firm, solid and satisfying.

The practitioner of the first always tries to conceal his addiction, because it always redounds to shame and reproach,

while the cultivation of the second, both in antiquity and at almost all periods, has been the source of the highest renown and glory in the field of learning.

No philosopher of any worth, eager in pursuit of the good arts, was ever a student of the former, but to learn the latter, Pythagoras, Empedocles, Plato and Democritus crossed the seas. Returning to their homes, they, in turn, taught it to others and considered it a treasure to be closely guarded.

The former, since it is supported by no true arguments, is defended by no writers of reputation; the latter, honored, as it were, in its illustrious progenitors, counts two principal authors:

Zamolxis, who was imitated by Abaris the Hyperborean, and Zoroaster; not, indeed, the Zoroaster who may immediately come to your minds, but that other Zoroaster, the son of Oromasius.

It we should ask Plato the nature of each of these forms of magic, he will respond in the Alcibiades that the magic of Zoroaster is nothing else than that science of divine things in which the kings of the Persians had their sons educated to that they might learn to rule their commonwealth on the pattern of the commonwealth of the universe.

In the Charmidcs” he will answer that the magic of Zamolxis is the medicine of the soul, because it brings temperance to the soul as medicine brings health to the body.

Later Charon-Jas, Damigeron, Apollonius, Osthanes and Dardanus continued in their footsteps, as did Homer, of whom we shall sometime prove, in a “poetic theology” we propose to write, that he concealed this doctrine, symbolically, in the wanderings of his Ulysses, just as he did all other learned doctrines. They were also followed by Eudoxus and Hermippus, as well as by practically all those who studied the Pythagorean and Platonic mysteries. Of later philosophers, I find that three had ferreted it out: the Arabian, Al-Kindi, Roger Bacon and William of Paris.

Aristotle used to say that the books of the Metaphysics in which he treats of divine matters were both published and unpublished.

CABALA – Transmission

Because the true interpretation of the law given to Moses was, by God’s command, revealed in almost precisely this same way, it was called “Cabala,” which in Hebrew means the same as our word “reception.”

The precise point is, of course, that that doctrine was received by one man from another not through written documents but, as a hereditary right, through a regular succession of revelations.

After Cyrus had delivered the Hebrews from the Babylonian captivity, and the Temple had been restored under Zoroba-bel, the Hebrews bethought themselves of restoring the law.

Esdras, who was head of the church at the time, amended the book of Moses.

The Pentateuch is the first five books of the He–brew Bible as well as of the Christian Old Testament. The designation “Pen–tateuch” derives from Greek penta (five) plus teûchos (vessel, in the sense of a case for scrolls). These five books are Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. They are also collectively called the Torah. Until the late nineteenth century, the consensus view of biblical scholars was that Moses wrote these first five books of the Bible. The Church father Jerome (ad 340–427), however, suggested that Ezra the Priest wrote the Pentateuch in the fifth century bc based on notes made by Moses. Since the sixth century ad, doubts have been expressed about whether Moses was the author of all the Penta–teuch. But it was only in the mid- seventeenth century that the first relatively systematic discussion of the issue appeared. By the late nineteenth century, the scholarly consensus began to turn against Moses being the author of any part of it. Yet in the Bible are references to the Pentateuch’s being “the book [sephar] of Moses” (Ezra 6:18 and Neh. 13:1) and to Moses’s knowing how to write (Exod. 17:14, 24:4, 34:27–28; Num. 33:2). It would then seem to require an explanation for the rejection of Mosaic authorship that is now the standard view in the scholarship

Esdras readily realized, moreover, that because of the exiles, the massacres, the flights and the captivity of the people of Israel, the practice established by the ancients of handing down the doctrines by word of mouth could not be maintained. Unless they were committed to writing, the heavenly teachings divinely handed down must inevitably perish, for the memory of them would not long endure. He decided, consequently, that all of the wise men still alive should be convened and that each should communicate to the convention all that he remembered about the mysteries of the law. Their communications were then to be collected by scribes into seventy volumes (approximately the same number as there were members of the Sanhedrin).

So that you need not accept my testimony alone, Oh Fathers, hear Esdras himself speaking: “After forty days had passed, the All-Highest spoke and said: The first things which you wrote publish openly so that the worthy and the unworthy alike may read; but the last seventy books conserve so that you may hand them on to the wise men among your people, for in these reside the spring of understanding, the fountain of wisdom and the river of knowledge. And I did these things.” These are the very words of Esdras. These are the books of cabalistic wisdom.

In these books, as Esdras unmistakably states, resides the springs of understanding, that is, the ineffable theology of the supersubstantial deity; the fountain of wisdom, that is, the precise metaphysical doctrine concerning intelligible and angelic forms; and the stream of wisdom, that is, the best established philosophy concerning nature.

Pope Sixtus the Fourth, the immediate predecessor of our present pope, Innocent the Eighth, under whose happy reign we are living, took all possible measures to insure that these books would be translated into Latin for the public benefit of our faith and at the time of his death, three of them had already appeared. The Hebrews hold these same books in such reverence that no one under forty years of age is permitted even to touch them. I acquired these books at considerable expense and, reading them from beginning to end with the greatest attention and with unrelenting toil,

I discovered in them (as God is my witness) not so much the Mosaic as the Christian religion. There was to be found the mystery of the Trinity, the Incarnation of the Word, the divinity of the Messiah; there one might also read of original sin, of its expiation by Christ, of the heavenly Jerusalem, of the fall of the demons, of the orders of the angels, of the pains of purgatory and of hell. There I read the same things which we read every day in the pages of Paul and of Dionysius, Jerome and Augustine.

ORPHIC THEOLOGY

In philosophical matters, it were as though one were listening to Pythagoras and Plato, whose doctrines bear so close an affinity to the Christian faith that our Augustine offered endless thanks to God that the books of the Platonists had fallen into his hands.

Of Pythagoras, however, Iamblicus the Chaldean writes that he took the Orphic theology as the model on which he shaped and formed his own philosophy. For this precise reason the sayings of Pythagoras are called sacred, because, and to the degree that, they derive from the Orphic teachings. For from this source that occult doctrine of numbers and everything else that was great and sublime in Greek philosophy flowed as from its primitive source.