Botanical Sources of

The New World Narcotics

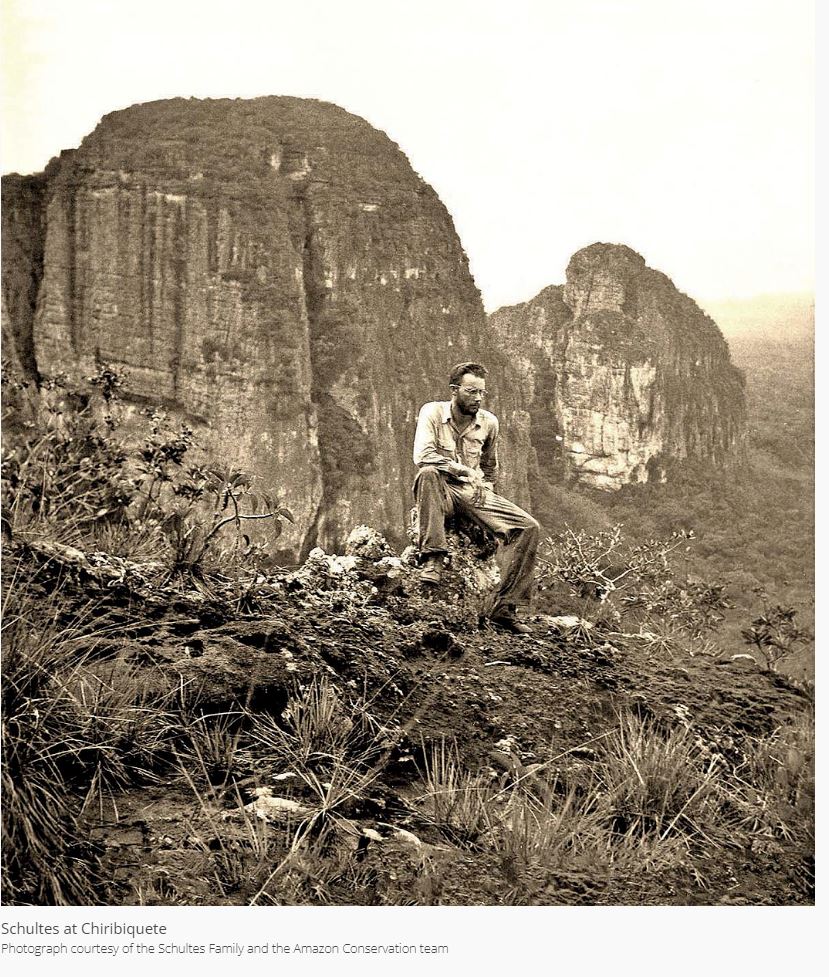

RICHARD EVANS SCHULTES

(SHULL-tees; January 12, 1915 – April 10, 2001)

A composite of two lectures (“Native narcotics of the New World” and “Botany attacks the hallucinogens?’’) delivered in the Third Lecture Series, 1960, College of Pharmacy, University of Texas, and published in the Texas Journal of Pharmacy 2 (1961) 141-185. Slight changes from the original text have been made in several places, and additional information has been added to bring the treatment of the subject up to date.

Richard Evans Schultes, Ph.D., is Curator of Economic Botany, Botanical Museum of Harvard University.

Man has learned to rely upon the plant kingdom not only for life’s necessities but also its amenities and ameliorants, in virtually every part of the world. None of the ameliorants has had a more absorbing history nor better shows man’s cleverness and ingenuity than those which we call the narcotics.

The very word “narcotic” has taken on a sinister meaning in American culture. There is probably no field — save perhaps religion and politics — so replete with popular misinformation and purposeful misrepresentation. This condition is general, yes, even universal, insofar as the public is concerned. But its paralysis has invaded even our technical circles. The misuse of the terms “habit-forming” and “addictive,” for example, is found even amongst our students. It is a fact that there are but two plant narcotics known to cause addiction and to be physically, morally and socially so dangerous that they must be strictly controlled — this fact is lost to most people, for whom it is enough that a substance be called a narcotic to draw away aghast.

I use the term “narcotic” in its classic sense. It comes from the Greek “to benumb” and, therefore, broadly applies to any substance (howsoever stimulating in one or several stages of its physiological activity) which may benumb the body.

The use of narcotics is always in some way connected with escape from reality. From their most primitive uses to their applications in modern medicine, this is true. All narcotics, sometime in their history, have been linked to religion or magic. This is so even of such narcotics as tobacco, coca and opium which have suffered secularization — which have come out of the temple, so to speak, have left the priestly class and have been taken up by the common man. It is interesting here to note that, when problems do arise from the employment of narcotics, they arise after the narcotics have passed from ceremonial to purely hedonic or recreational use. This historical background can explain much, especially when we realize that there are still some in primitive societies must be versed in and sympathetic to anthropological or ethnological fields — and we have come to refer to this type of scientist as an ethnobotanist.

None of the New World narcotics, save tobacco and coca, has assumed a place of importance in modern civilization, and many are still rather un¬familiar even to our botanists, chemists and pharmacologists. It is for this reason that I have chosen, even at the risk of seeming rather superficial, to say a few words about each of the native New World narcotics, with almost all of which I have had personal experience in the field over a long period. By doing this, I hope to give you an overall picture of what we may term the “narcotic complex” of New World peoples. For sundry of these, the literature, though recondite, is extensive, covering many fields of research; but for the greater number, bibliographic sources are few and pertain to only one or two fields of investigation. Reference to tobacco and alcohol, both native American narcotics, will be omitted from this brief article.

The identification of the source plants of American narcotics has interested me since 1936. Consequently, it is natural, I suppose, that my remarks should be heavily botanical. That the final and complete understanding of- narcotic plants rests solely and fundamentally on a knowledge of their botan¬ical sources makes it obvious that the first step must be made in the direction of botany or ethnobotany. Convinced of the importance of this step, I have studied narcotic plants among North American Indians in Oklahoma, have made several trips into the Mazatec, Chinantec and Zapotec Indian country of northeastern Oaxaqa, Mexico, and lived almost without interruption, from 1941 to 1953, in the northwest Amazon and the northern Andes of South America.

For some of the plants mentioned, there are no chemical, much less phar¬maceutical, data. For some, even, there are still serious problems concerning their botanical source or sources. Here, then, lies one of the most promising fields for research, for we know that tropical America still holds secrets in connection with narcotic plants.

For general purposes, there is probably no more serviceable classification of the plants man uses in his striving for temporary relief from reality than that proposed by the German toxicologist, Louis Lewin.

Of Lewin’s five categories, i.e., Excitantia, Inebriantia, Hypnotica, Eurphorica, Phantastica, none has stirred deeper interest through the ages, and none has foretokened a greater field for discovery for the present and future, than the Phantastica. There have recently been proposed very learned and intricate words to distinguish the several kinds of narcotics. Our modern terminology has come to call these the hallucinogens, the psychotomimeties, or the psychedelics. Differing from the psychotropic drugs, which normally act on the central nervous system to bring about a dream-like state, marked (as Hoffmann points out) by extreme alteration in the “sphere of experience, in the perception of reality, changes even of space and time and in consciousness of self.” They invariably induce a series of visual hallucinations, often in kaleidoscopic movement and usually in rather indescribably brilliant and rich colors, frequently accompanied by auditory and other hallucinations and a variety of synesthesias. Notwithstanding this mushrooming new nomenclature, it seems to me difficult to find a simpler and more serviceable classification than that of Lewin.

It is of interest that the New World is very much richer in narcotic plants than the Old and that the New World boasts at least 40 species of hallucinogenic or phantastica narcotics as opposed to half a dozen species native to the Old World.

It is clear that medical and psychological research into these strange agents, at a painfully embryonic state at the present time, promises more than we are able fully to comprehend. Powerful new tools for psychiatry may be only one of the results of such investigations. But research into the effects of these substances on the human mind must be carried out carefully, without haste or superficiality and, above all, by the most qualified personnel, for what may be one of the most promising fields for progress ever within man’s grasp can easily be jeopardized or utterly destroyed by irresponsible and inadequately – planned research or by the manipulations of dilettantes.

Ayahuasca, Caapi, Yaji

One of the weirdest of our phantastica or hallucinogens is the drink of the western Amazon known as ayahuasca, caapi or yaje. Although not nearly so popularly known as peyote and, nowadays, as the sacred mushrooms, it has nonetheless inspired an undue share of sensational articles which have played fancifully with unfounded claims, especially concerning its presumed telepathic powers.

In spite of its extraordinarily bizarre ability to alter man’s physical and mental state, this narcotic drink finally disclosed itself to prying European eyes only about a century ago. And it remains one of the most poorly understood American narcotics today.

The earliest mention of ayahuasca seems to be that of Villavicencio in his geography of Ecuador, written in 1858. The source of the drug, he wrote, was a vine used “to foresee and to answer accurately in difficult cases, be it to reply opportunely to ambassadors from other tribes in a question of war; to decipher plans of the enemy through the medium of this magic drink and take proper steps for attack and defense; to ascertain, when a relative is sick, what sorcerer has put on the hex to carry out a friendly visit to other tribes; to welcome foreign travellers or, at least, to make sure of the love of their womenfolk.”

A few years earlier, in 1852, that tireless British plant-explorer. Richard Spruce, had discovered the Tukanoan Indians of the Uaupes in Amazonian Brazil using a liana known as caapi to induce intoxication. His observations were not published until the posthumous account of his travels appeared in 1908.

One of Spruce’s greatest contributions to science was his precise identification of the source of caapi as a new species of the Malpighiaceae which was called Banisteria Caapi. The correct name is now Banisteriopsis Caapi, since it has been shown to be not a true Banisteria.

The natives of the upper Rio Negro of Brazil use it for prophetic and divinatory purposes and also to fortify the bravery of male adolescents about to undergo the severely painful yurupari ceremony for initiation into manhood. The narcosis amongst these peoples, with whom I have taken caapi many times, is pleasant, characterized, amongst other strange effects, by colored visual hallucinations. In excessive doses, it is said to bring on frighteningly nightmarish visions and a feeling of extremely reckless abandon, but consciousness is not lost nor is use of the limbs unduly affected.

Two years later, in 1854, Spruce encountered the intoxicant along the upper Orinoco, where the natives chewed the dry stem for the intoxicating effects. Again, in 1857, he came upon ayahuasca in the Peruvian Andes and concluded that it was “the identical species of the Uaupes,—but under a different name.”

Later explorers and travellers — Martius, Orton, Crevaux, Koch-Grunberg and others — referred to ayahuasca, caapi or yaje but in an incidental, even casual, manner. All agreed, however, that the source was a forest liana.

In the years following the early work, the area of use of Banisteriopsis Caapi was shown to extend to Peru and Bolivia, and several other species of the genus with the same use were likewise reported from the western Amazon. Of outstanding interest was the work in 1922 of Rusby and White in Bolivia and the publication by Morton in 1931 of notes collected by Klug in the Colombian Putumayo. Similarly, the work of the Russians Varonof and Juzepczuk in the Colombian Caqueta in 1925-6 added information of interest to the whole picture.

Serious complications, however, early entered the story of the correct identification of ayahuasca, caapi and yaje. Back in 1890, Magelli, a missionary in Ecuador, through a misuse of the native names for Jivaro intoxicants, confused our malpighiaceous vine-narcotics with one of the tree-species of Datura. The effects of the two psychotomimetics differ widely. This con¬fusion, fortunately, did not enter the pharmacological or chemical literature.

A complication which has, however, sorely plagued both the botanical and the chemical literature, even as recently as 1957, stems from the days of Spruce. This meticulous observer noted, when he discovered caapi and identified its source, that another kind called caapi-pinima or “painted caapi” in the

Rio Negro area might be ‘in apocynaceous twiner of the genus Haemadictyon,

of which I saw only young shoots without any flowers.

‘The leaves,” he wrote, “are of a shining green, painted with the strong blood-red veins.

to be continued….