One in Two Worlds: American-Born Sita Sharan Divides Her Time Between Colorado and India, Practicing 4,000-Year-Old Rituals of Orthodox Hinduism

‘Before god, we are all women.’

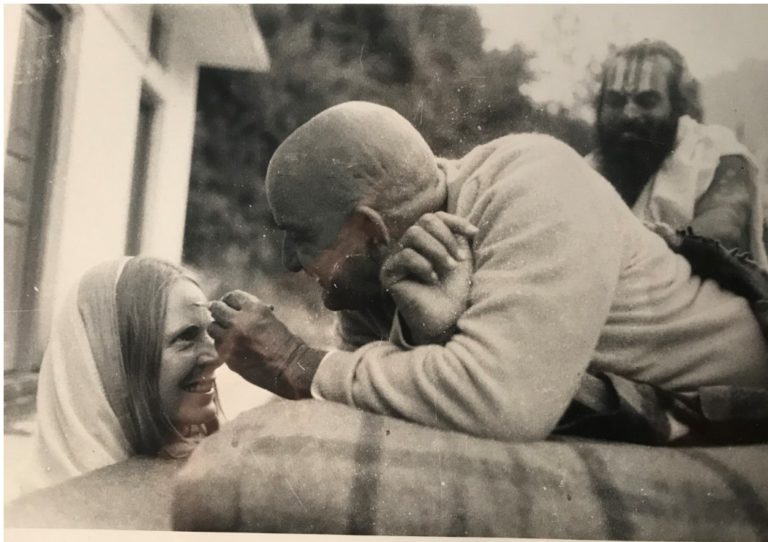

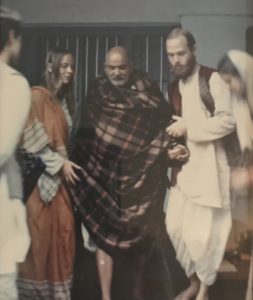

Chitrakoot Mouni Baba

Chitrakoot Mouni Baba and Sita

The following is from an interview clip with Ed Reither (Beezone) and Sita in 2019 in Boulder, Colorado.

“I was going to be a sadhu”

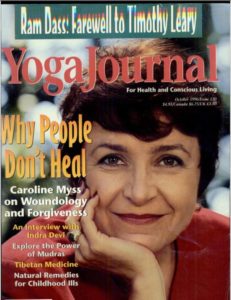

Sita Sharon

***

One in Two Worlds

By Amy R. Kaplan (Yoga Journal, October 1996, Issue 130)

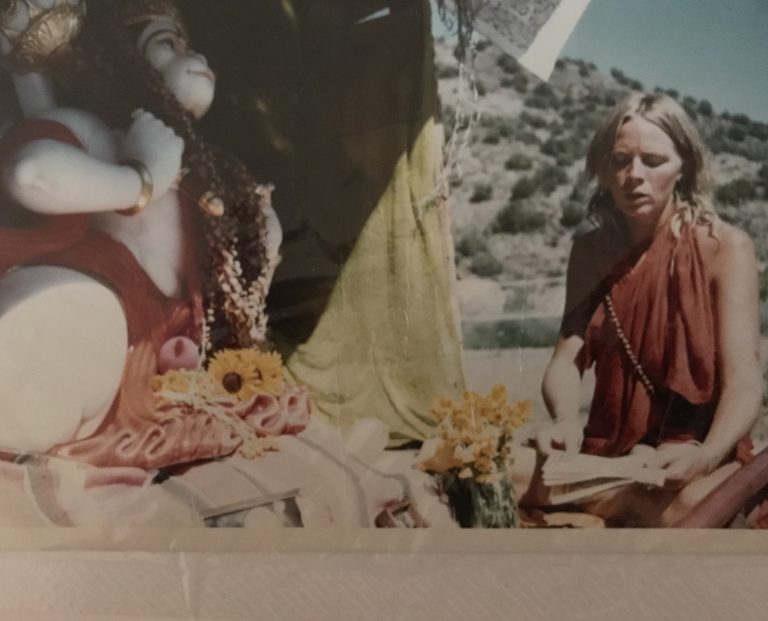

Even with my eyes closed, I know this can’t be India. The air is too cool, the river too loud. Emerald hummingbirds dart past the windows, and ground squirrels peer in. The heartbeat of a tabla merges with the soothing recitation of ancient Sanskrit mantras. Sita sits cross-legged on a deerskin, raised slightly above the other participants. All around are the accouterments of a Hindu sadhu: fruit, flowers, a conch shell, a large stone Shiva lingam, bells, candles, a bronze Ganesh, and one discordant object – a small American flag.

Sita Sharan is indeed a sadhu (‘virtuous one”) and a priestess in an ascetic discipline that usually disallows women. She spends six months each year following the life of a sadhu in India. The other six months, she lives In the Colorado Mountains as a recluse and occasional lecturer in Hindu ritual and traditional practice. This particular afternoon, she is performing her dally fire ceremony In front of guests.

“Do you have a permit for this?” a Denver woman asks with concern.

Sita laughs. “Of course not. It’s one of so many contradictions. In America they say you cannot make a fire during a drought. In India they say there will never be rain until the sacrifice is made.”

As the room absorbs the gentle smoke and crackling sounds of her ritual offerings, Sita’s pale eyes, blonde hair, and fair complexion warm with the reds, oranges, and golds reflecting off the brass and copper vessels around her. Her guests finger japa (recitation) beads, mesmerized by her soft soprano voice and the deft movements of her hands: pouring, polishing, and tracing patterns in the air to the rhythm of her chanting. Bells sound, then the conch. The sound of the river fills the silence as flower petals fall into the flames, then ghee, spices, and rice.

“I change this puja daily depending on the mood and the time available,” says Sita in a low, animated voice. “These toys?” she asks, indicating the small spinning top, dice, and a tiny gun. “Krishna, he’s a playful one.” She motions to the Indian print at the back of her altar. “He plays with a gun, only this isn’t a gun, it’s a water pistol.”

Before she resumes chanting, she briefly explains, “The fire deity is the priest of the gods. Agni, the many-tongued fire, is the messenger who carries the burnt offerings. Agni purifies everything it is offered, and in exchange blessings are bestowed.”

She adds more wood, dried dung, and aromatics to the flames. May Agni release me from every fault and sin. Swaha. She ritually washes her hands and takes three swallows of water for the purification of body, speech, and mind. 0 Agni, great friendly deity; call forth from the gods benevolence toward heaven and earth for us. Swaha. The flames rise higher. May the waters release their beloved streams. Let ciklita abide in my abode, and cause your mother, the goddess Sri to dwell in my house. Swaha. Outside the aspen trees quiver and a gentle rain begins to fall.

Later we walk by the river and Sita talks about her life.

“All this started at school in Montréal. The Catholic sisters would send me to the neighborhood soda fountain for milkshakes and burgers. On the counter sat a row of swami-shaped napkin holders with penetrating eyes-my first exposure to Eastern philosophy.”

“Whenever I needed an authority to relieve my worries or warn me about the future, I would find a place on a swing-around stool at the counter and, while I composed my questions, I would stare at the swami’s foreign face and jeweled turban. The napkins were free, but I saved up my nickels, because for just five cents I could tug on the handle of the holder and get a pink slip of paper printed with an important message: an answer to the questions the priests and nuns couldn’t or wouldn’t, answer.

“I was looking for something with more mystery, more reassurance than Catholicism. How could it be that the early Christian martyrs could gain heaven with only one act of faith? It seemed too easy.”

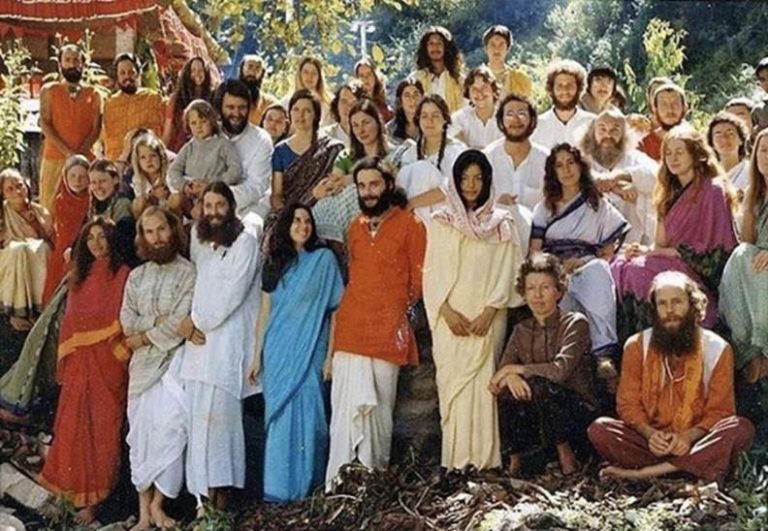

In the 1960s her brother went to India, and Sita heard Ram Dass talk on the radio. “He spoke with such authority that that summer I went to his farm in New Hampshire. All I’d read until then was one book on yoga. The Bible says when you find a teacher, you stay with him, and so although Ram Dass brushed me off with only a mala and pictures of himself and his guru, Neem Karoli Baba, it was a kind of starter set for the spiritual life. I knew if he could go to India, so could I. I was 19.”

In India Sita studied vipassana meditation with Sri Goenka and Anagarika Menendra, then she and her brother showed Neem Karoli’s picture around, trying to get directions to his ashram. She laughs that neither of them knew enough Hindi to understand the answers they received. She ended up in Nainital, where she had gone to ride horses, and showed the picture again. This time she got lucky—the ashram was nearby. “

Neem Karoli Baba’s group welcomed me generously, and my training began,” Sita recalls. “I had one bag and a blanket, so I learned what renunciation meant.” The uncluttered life became an obsession. But Neem Karoli Baba wasn’t a curriculum-oriented guru. He was a traditional Hindu saint, who tended to send people elsewhere. Again she was brushed off, this time to Benares to learn music.

“For years I sat with my singing teacher, the late Amiya Babu, going up and down the scales, imitating like crazy. Neem Karoli Baba thought music would meet my special needs for discipline and soften my emotional edges. But my teacher thought I didn’t have enough ability to ever be brought into tune.”

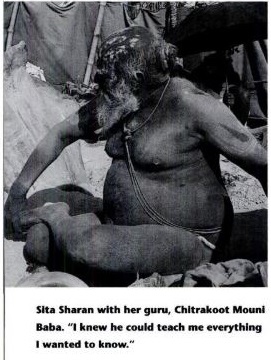

In 1974, after Neem Karoli Baba left his body, Sita traveled on to the kumbha mela (a great religious festival that takes place every six years) where she lived with sadhus, totally outside the company of Westerners. She took on the vermilion trident marking of the Vaishanav sect and moved on to Chitrakoot, the home of Mouni Baba, who would become her spiritual master.

Chitrakoot Mouni Baba and Sita

“I knew he could teach me everything I wanted to know. He called my training ‘polishing’ and sent me on a pilgrimage to the holy places in the Himalayas. I traveled alone for four years as a holy man, from village to village, sleeping by hearths or outdoors and only eating the fruits, vegetables, milk, buckwheat, and potatoes that I was offered. Only once was my being a Westerner and a woman questioned, but after the village headman checked the contents of my bag, he knew I was authentic. In India, there’s a higher order of hospitality which overrides all caste restrictions.”

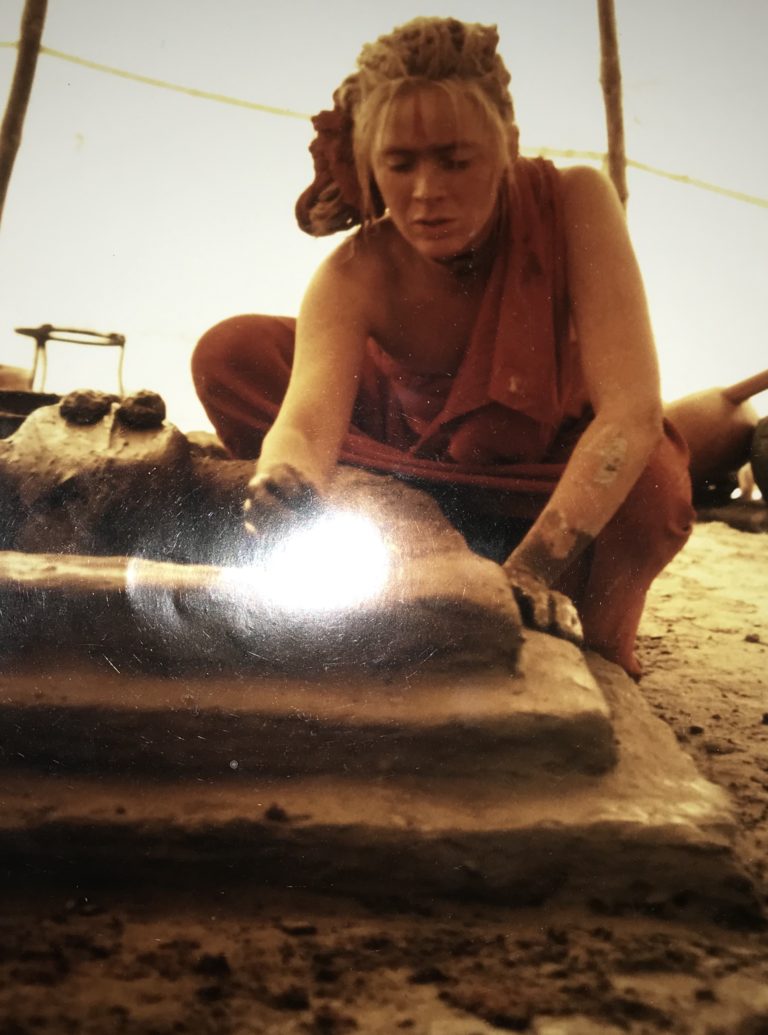

Sometime during the first year in the company of Mouni Baba, he realized Sita didn’t yet know Sanskrit. “I was reading to him, the Ramayana text, but only phonetically. Lying there, he made me go over and over each line until I got it right. He should have given me an F and dismissed me, but instead he put his bare foot on my shoulder, and while I slowly put the sounds together, he slid his toe into my ear, like he was making some fine-tuning adjustment. After that I took on a private tutor for Sanskrit and medieval Hindi. I realized that getting by with modern Hindi wasn’t enough if I was ever to actually embrace the tradition and become a practitioner.”

Years later, with a knowledge of the music and the languages in her pocket, Sita gave herself over totally to the simplicity and ritual of a sadhu’s life. She practiced the ancient traditions and highest levels of austerities. With her hair in dreadlocks smeared with ashes, drinking no water, she sat surrounded by fires in the hot season, meditated on winter nights submerged in the freezing waters of the Ganges, and many times repeated the three miles of prostrations around Kamadgiri, one of India’s holiest mountains.

“Mouni Baba broke all the rules to initiate me into the exclusively male Tragi tradition of the highest renunciates. When other high-ranking gurus would challenge me, I’d just say, ‘You’re absolutely right, but I’m only doing as he instructed.’ One time in Benares, when we were challenged again, he ended the discussion by saying simply, ‘Before god, we are all women.’

“Mouni Baba was my swami in the napkin holder. Despite his gentle nature, he was a five-star general: feared and loved. He practiced only the most extreme orthodoxy. Being with him, I came home, but it wasn’t until years later that I learned I could also be at home in the States.” With that, she told her lipstick story.

Sita always wears a pale shade of lipstick, a rather unusual practice for a sadhu. “I decided that if I used just a little bit, maybe they wouldn’t notice,” she says. Once on a visit to a venerated saint in Ayodhya, she dropped her bag and, without her noticing, her Revlon rolled out. As she left, one of the disciples ran after her down the road to return it. “From that point on, using lipstick in India was no longer an issue. He’d seen me wear it, and, by giving it back, he was saying it was alright. In India I can wear lipstick without it being a hypocrisy, but in the West people really don’t want you sitting on their couches or sleeping on their bed sheets with ashes in your hair.”

Her life in Colorado is solitary and her practice is definitely not fashionable. “I practice the rituals that have their roots in the 4,000-year-old culture of orthodox Hinduism. In the West, the influence of Eastern thought and yoga have become established in the past 30 years. They’re nearly mainstream. Now almost every city has a yoga and meditation center. Some are affiliated with big organizations, others are renegade, but they all perform an important service. In this age where the individual creates reality, a tremendous alienation has resulted. These centers are preparing people through physical and mental training to experience a loosening of the mind, moving them toward shared values.

Historians say it takes 50 years for any significant influence to penetrate a culture. We’re now 35 years into this shift of consciousness, and in the next 15 years perhaps we’ll see something develop from its influence.”

Two weeks later Sita performs another fire puja, this time in the living room of a member of the Indian community. Unlike the Westerners of the previous group, these people, occasionally chanting in unison, allow her to guide them back to a world where they already belong. Afterwards they don’t speak in the hushed tones that seem so appropriate in the presence of someone holy. This group’s admiration and respect are for Sita’s remarkable knowledge and her mastery of the sacred text and traditional ritual.

“Hindus in America only want to remember. They already know what it’s about. It’s a part of their lives, even without daily practice. When I perform ritual, I feel like I’m repaying a debt to their society, which has enriched my life. I bring them something that has enriched my life.”

For Sita, as for all renunciates, the daily practice of virtue is what is most important. “My time in India is like a six-month intensive. Although I don’t wear ashes in my hair or on my body anymore, I enjoy the community of holy men and spiritual discourses. You can rarely be alone in India, which is why I also need my six months here.”

Living in the Colorado Mountains, she enjoys the luxuries of solitude, clean air, good water, and comfortable weather. She listens only to Hindu spiritual music and classical ragas and maintains her diet of no meat, fish, eggs, onions, or garlic. “It’s the simplicity and practice that are important. While life in America is not simple, I serve God just as well here.”

Sita does not see herself taking on disciples in the traditional sense, although she speaks publicly on Hinduism and performs fire ceremonies under the auspices of her “wide-open secret society,” Sackcloth and Ashes. She also teaches ritual at Naropa Institute and through the Rocky Mountain Institute of Yoga and Ayurveda. “I emulate what I’ve been taught. In the West we tend to think Enlightenment is just a breath away and the end of the road. But it’s a project over many lives of practice. I can be helpful only as an example.

“Any transformational aspect of my tradition comes in the context of India. For Westerners, all I can teach is the inherent value of ritual. There’s evidence that when people are in holy places they do experience something beneficial. I give them a glimpse into a tradition, a genuineness of lineage separate from me as a person. The practice gives the benefit, not anything I say or do or carry with me.”

A year ago a family visited her in the mountains with their unruly 11-year-old son. He’d seen a fire puja at an ashram in Taos. “Let’s have a fire, we must have a fire,” he nagged. So she lit one. “But aren’t we going to throw any offerings in?” “Okay, I’ll give you some offerings,” she told him. He protested further: “No, you have to say the words.” She chanted some Sanskrit and made a few offerings, but that was not enough. The boy took over, “May my mother and father be happy. Swaha. May my friends get along with each other. Swaha. May there be peace in the world. Swaha.”

“It’s not the foreign ritual that’s important,” Sita says. “It’s our human condition that’s looking for ceremony, worship, and prayer. Even this boy knew the fire had meaning and felt that meaning in the fire.”

Amy R. Kaplan is a freelance writer in Boulder, Colorado.