From Tantalus to Technopoly:

Rediscovering F.C.S. Schiller’s Prophetic Voice

By Beezone

Prologue: A Forgotten Vision

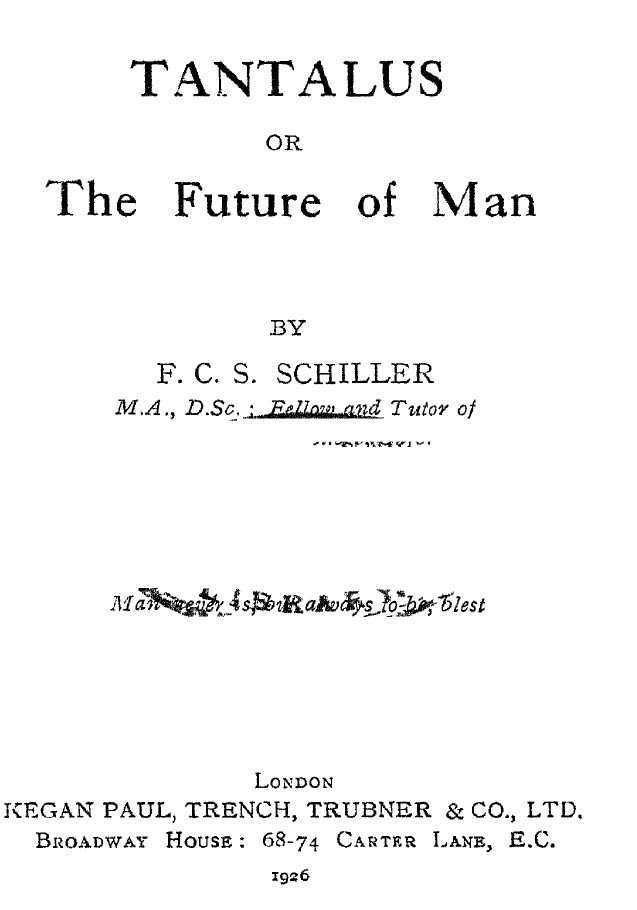

In 1926, the English philosopher F.C.S. Schiller published a book with an unusual title and a strangely mythic overture: Tantalus, or The Future of Man. Nearly a century later, the book has all but vanished from public conversation, its author forgotten even among many historians of ideas. Yet its pages—rich with metaphor, biting wit, and cultural premonition—read with the eerie familiarity of someone who saw us coming.

When I read in Mr Haldane’s Daedalus the wonderful things that Science was going to do for us, and in Mr Russell’s Icarus how easily both we and it might come to grief in consequence, it at once became plain to me that of all the heroes of antiquity Tantalus would be the one best fitted to prognosticate the probable future of Man. For, if we interpret the history of Daedalus as meaning the collapse of Minoan civilization under the strain imposed on its moral fibre by material progress, and the fate of Icarus as meaning man’s inability to use the powers of the air without crashing, one could gauge the probability that history would repeat itself still further, and that man would once more allow his vices to cheat him of the happiness that seemed so clearly within his reach. – F.C.S. Schiller, Prologue: The Oracle of the Dead

If Aldous Huxley, Bertrand Russell, and Neil Postman form the canon of 20th-century critics of modernity—warning of what happens when science and technology unmoors itself from ethics, or when media entertainment replaces the publics ability to reason—then Schiller ought to be considered their grandfather. Tantalus was published before Brave New World (1932), before Orwell’s 1984, before Marshall McLuhan, before even the first real mass media age. And yet, there he is in 1926, describing a civilization intoxicated by progress, exhausted by knowledge, and still haunted by its paleolithic impulses.

Rather than deliver a treatise, Schiller begins with a vision. He dreams himself into the underworld and consults the spirit of Tantalus—the tragic figure of Greek myth who, having stolen from the gods, was condemned to stand in a pool of water beneath a fruit tree that forever receded from his grasp. Water just out of reach. Fruit that turns to ash. Hunger and thirst sharpened by proximity to satisfaction.

Tantalus, Schiller suggests, is not simply a figure from ancient mythology; he is modern man himself. Endowed with astonishing powers—scientific, technological, intellectual—we stand at the base of a tree of knowledge whose fruit continues to explode in our hands. Our inventions intoxicate us, then poison the well. Our capacity to manipulate the world has outpaced our ability to understand ourselves.

Schiller had read J.B.S. Haldane’s utopian Daedalus and Bertrand Russell’s cautionary Icarus, both published just two years prior. But rather than cast himself as a commentator, he chose instead to consult the “oracle of the dead.” The result is a strange, startlingly creative work—a dialogue between dream and diagnosis. It reads like Plato rewritten by Jonathan Swift.

What emerges from Schiller’s descent is not a clean argument but a layered metaphor: humanity has climbed the ladder of power without adjusting its moral spine. His Tantalus is deformed from the waist down—well-formed in intellect and will, but misshapen in his capacity to walk a straight path or reach for what truly nourishes.

And here is where Schiller begins to intersect with Neil Postman. Fifty years later, Postman would argue that Americans had become the first people in history to be “amused to death,” victims of a culture that turned every idea into entertainment, every serious issue into spectacle. He warned that we had built a “Technopoly,” a culture in which all problems are assumed to have technical solutions, and where technology is not merely a tool, but a way of knowing, judging, and organizing reality itself.

Both men, in different voices, are warning of a civilization drunk on its own reflection. Schiller offers the myth. Postman, the media critique. One writes in allegory; the other in analysis. But both speak of a society that has lost its way precisely because it believes it has found it.

The rediscovery of Schiller matters not just because of historical curiosity. It matters because we have, if anything, accelerated the conditions he feared. The academic institutions that Schiller called clogged with “waste products of their own working” now face crises of legitimacy and purpose. The fruit of technological advancement—AI, genetic editing, global surveillance—still dangles just out of moral reach. And our Tantalus still stirs in the mud, distracted, deformed, and unredeemed.

Tantalus: Myth, Memory, and Modern Relevance

In Greek mythology, Tantalus was a king—favored by the gods, admitted to their table—who committed the unspeakable crime of offering his own son, Pelops, as a feast to the immortals. For this act of hubris and betrayal, he was condemned to Tartarus, a shadowy underworld of eternal punishment. There, he stands in a pool of water beneath a fruit-laden tree, tormented by hunger and thirst. Each time he bends to drink, the water recedes. Each time he reaches for the fruit, the branches lift away.

The image is unforgettable. It is not a punishment of pain, but of deprivation sharpened by nearness. The gods did not strike him down or torture him in flames. They placed him in the very presence of abundance—and made satisfaction impossible. His curse was the promise of fulfillment, eternally withdrawn.

This myth, which haunted ancient writers from Homer to Pindar, has long been read as a parable about temptation, punishment, and the limits of divine tolerance. But in Schiller’s hands, the myth becomes something far more subtle—and disturbingly familiar. His Tantalus is not simply a figure of moral corruption, but a portrait of modern civilization itself.

In Schiller’s vision, Tantalus is no longer a king in punishment, but a human everyman—powerful, determined, half-formed. His upper body reflects strength, intellect, and ambition. His lower body is grotesque, incapable of proper locomotion. He churns the very Elixir of Life into mud with his clumsy feet, and reaches compulsively for the tree’s fruit, which now explodes on contact. The tree, we are told, is the Tree of Knowledge.

Here, Schiller inverts the Edenic myth without rejecting it. Knowledge is not forbidden—it is available, even desirable—but it is also volatile, sometimes poisonous. The punishment is no longer imposed by gods. It is self-inflicted. Man reaches too soon, or for the wrong fruit, or without understanding, and suffers the consequence. There is no serpent in this version, only blindness and willfulness.

The genius of Schiller’s metaphor is in its layers. The tree bears fruits of many kinds—some seductive, some beneficial, some deadly. The water beneath it is life-giving, but the means of reaching it are blocked by a perimeter of bones and stingers—”debris of former animal life,” Schiller writes. The path to wisdom, or even survival, is hemmed in by the remnants of past experiments, conquests, and failures.

The tragedy is not just that man cannot reach the fruit, but that he insists on reaching for the lowest-hanging ones, over and over, despite the consequences. He does not climb. He does not learn. He does not stop.

This image—of a half-deformed seeker compulsively grasping at the tools of his own destruction—prefigures what Postman, decades later, would describe as a society of “technological sleepwalkers.” A culture that rushes to adopt every new invention without asking what problem it solves, what value it threatens, or what it does to the human soul.

Tantalus, in this updated myth, is not damned by the gods. He is damned by his own confusion.

The Institutional Mirage: When Memory Becomes Machinery

Having reimagined Tantalus as the emblem of modern man, Schiller turns his gaze from myth to society, and from allegory to analysis. He asks a deceptively simple question: If man has stopped evolving biologically, why has he continued to develop culturally, intellectually, and technologically? His answer is equally simple, at first: because man invented memory.

Not personal memory, but social memory—the capacity to preserve knowledge across generations through language, writing, and education. These tools, Schiller writes, gave rise to institutions: religions, schools, governments, scientific academies. These, in turn, allowed human beings to accumulate wisdom far beyond what a single lifetime could acquire.

But what begins in celebration quickly turns to suspicion. “Human institutions,” Schiller warns, “like the human body, are ever tending to get clogged with the waste products of their own working.” The very structures that preserve knowledge can come to obscure it. The very systems that carry culture forward can begin to pull it backward.

Churches deaden faith through rote ritual. Law stifles justice in a thicket of technicality. Schools extinguish curiosity in the name of examination. And nowhere is the paradox more sharply drawn than in Schiller’s portrait of the professor: the supposed steward of learning who, out of insecurity or ambition, renders his subject increasingly technical, inaccessible, and obscure.

“The interest of the subject,” Schiller writes, “is to become more widely understood and so more influential. The interest of the professor is to become more unassailable, and so more authoritative.”

This line could easily have been written by Neil Postman—or perhaps by Ivan Illich, whose Deschooling Society offered a similarly ferocious indictment. In both Schiller and Postman, we find the insight that institutions, once established, tend to prioritize their own survival over the truth they were created to serve. They grow more abstract, more rule-bound, more self-referential. And they do so, ironically, at the expense of the very memory they were supposed to safeguard.

For Postman, this manifests in the media landscape: television, and later the internet, flatten complex thought into snippets and images. Knowledge becomes entertainment. Discourse becomes performance. Information overload replaces understanding. “What we need,” Postman wrote, “are metaphors to remind us that technology is not part of the natural order of things, that it is a product of human choice.”

Schiller, decades earlier, was already sounding this alarm in a different key. His metaphor is not of technology, but of ossified tradition—dead professors and petrified dogma, whispering empty formulas into a culture that has mistaken repetition for wisdom. Progress, he insists, is never guaranteed. It can halt. It can regress. It can even destroy.

What’s most haunting is how Schiller foresees not only the corruption of institutions, but the complacency of the public in the face of that corruption. His Tantalus does not protest the fence of bones that separates him from the water of life. He merely shuffles around it, resigned to his loop. Likewise, Schiller seems to suggest, modern societies accept their own institutional decay not out of ignorance, but out of habit.

The Illusion of Progress: Are We Better Than Our Ancestors?

Schiller does not mince words: “Modern man has no right to boast himself far better than his fathers.” In this declaration lies one of the boldest reversals in Tantalus. Where the common story of modernity tells of ascent—from darkness to light, from ignorance to reason—Schiller sees, at best, a detour, and at worst, a decline masked by convenience.

From the viewpoint of biological evolution, he notes, humanity has been stagnant for tens of thousands of years. The Cro-Magnon man—six feet three inches tall, with a brain volume exceeding our own—was, in Schiller’s account, superior in both stature and raw capacity. What has changed is not our inner potential, but the external prosthetics we’ve devised: tools, institutions, and technologies that allow us to simulate intelligence and outsource memory. Our greatness, such as it is, lives not in us but around us.

And even that greatness, Schiller argues, is ambiguous.

Civilization has made us tamer, perhaps. More polite in our cruelty. But it has not fundamentally altered the moral core of man. Strip away the institutions, the norms, the regulatory mechanisms of society, and you will not find a sage or saint beneath the surface—you will find a Yahoo.

“Modern man is still substantially identical with his paleolithic ancestors. He is still the irrational, impulsive, emotional, foolish, destructive, cruel, credulous creature he always was.”

This is not cynicism for its own sake. It’s an indictment of the faith in progress as a self-correcting force. And it finds a natural heir in Postman, who, sixty years later, observed that “technological change is not additive; it is ecological.” A new invention doesn’t just slot into the old order—it reorders everything, including our self-perception. We believe we are advancing because our machines become more powerful. But do we become wiser? More just? More humane?

Schiller’s answer is clear: no. Or at least, not necessarily.

He goes further. He suggests that civilization, far from ennobling man, may actually deepen his danger. The more connected and complex a society becomes, the more devastating its failures become as well. A tyrant in a village can destroy a few lives. A tyrant with trains and telegraphs—and, today, with nuclear weapons and global networks—can destroy millions.

Postman would echo this in his own language. He warned that technological societies develop a peculiar kind of hubris: the belief that all problems are solvable, that information is equivalent to knowledge, and that more access, more speed, and more novelty must be good. But he, like Schiller, saw that man’s moral instincts do not evolve at the pace of his tools. They stall. They spiral. They repeat.

This is what makes Tantalus so modern in its despair. It is not a call to abandon civilization, but a reminder that civilization, unaided by reflection, can become a kind of elegant barbarism—polished, fast-moving, efficient, and spiritually empty.

When Knowledge Forgets Itself: The Collapse of Meaning in an Overeducated World

For Schiller, the miracle of civilization rests on one fragile premise: that human beings can store and transmit the wisdom of the past. What distinguishes man from beast is not merely reason or language, but the invention of a social memory—the ability to retain, accumulate, and teach what no individual could gather in a single lifetime.

This begins with language, which allows for oral tradition. It blossoms with writing, which allows memory to become permanent. And with education, knowledge can become institutionalized, even routine.

But here lies the trap.

Schiller warns that mechanized memory, once divorced from lived meaning, can easily become antithetical to the very wisdom it was designed to preserve. He devotes several scathing pages to what he calls the “waste products” of human institutions—how churches dull faith, how schools smother curiosity, and how academic life often thrives by making knowledge so technical, so inaccessible, that it can no longer guide the society that funds it.

“Educational systems become the chief enemies of education, and seats of learning the chief obstacles to the growth of knowledge.”

This paradox would become one of the great themes of Neil Postman’s work. In Technopoly, Postman argues that in a society dominated by information, meaning becomes elusive. He warns of a future in which people have access to vast databases, endless news, and infinite “content”—but cannot distinguish what matters from what merely distracts.

“Information,” he writes, “has become a form of garbage, not only incapable of answering the most fundamental human questions but barely useful in helping us to ask them.”

Schiller anticipates this decades earlier. His fear is not ignorance, but misdirected knowing—a world where knowledge is no longer for anything, where learning becomes jargon, where tradition becomes ritual, and where the past becomes a series of unexplained formulas taught by teachers who no longer believe them, to students who never understood them.

In such a world, even the most refined cultural memory can decay into noise.

He illustrates this with examples that sound startlingly contemporary: professors of economics retreating into mathematical formalism, making their discipline unintelligible to the public—and thus irrelevant to the political decisions that shape the economy. The Treaty of Versailles, he notes, was signed by leaders so economically illiterate that even John Maynard Keynes, for all his clarity, could not dissuade them from imposing conditions that would bankrupt Europe.

One is reminded of Postman’s concern about technocratic language, media saturation, and the cult of the expert—how all of these combine to sever knowledge from the public sphere, and render democracy itself vulnerable to manipulation.

In both Schiller and Postman, the question is not whether knowledge survives, but whether it lives.

And to live, knowledge must be reanimated by memory—not just stored in books or hard drives, but absorbed, reflected upon, and measured against the deep, human questions that machines cannot ask.

Schiller offers no solution—only a warning, cloaked in classical myth and early-modern irony. Postman does something similar, though with the clarity of a media theorist rather than a metaphysical ironist. But both insist that the meaning of knowledge—its use, its purpose, its transmission—must be held sacred, or it will corrode into absurdity.

The Tantalus Condition: Schiller, Postman, and the Mirror of Our Time

When F.C.S. Schiller imagined Tantalus in 1926—shuffling around a tree of knowledge, deformed, compulsive, fruit exploding in his hands—he was writing out of deep cultural disillusionment. World War I had shattered the illusion that Europe’s scientific and philosophical “progress” had secured civilization. The Enlightenment had bred machines of war. Academia had grown sterile. Society had grown clever but not wise.

Half a century later, Neil Postman would pick up the same mood, though from a different place: the postwar optimism of the American media age. His tone, calm and pedagogical, masked a growing despair. By the 1980s, he saw a society in which information was abundant but meaning scarce. People no longer read for wisdom but watched for entertainment. Schools no longer taught thinking but administered tests. The culture had traded truth for data, and memory for content.

Both Schiller and Postman describe a condition we might now call the Tantalus condition: a civilization flooded with knowledge and power, yet incapable of using either to reach fulfillment, coherence, or peace.

❖ The Convergence

-

Both believed institutions decay when they forget their founding purpose. Schiller saw the university lose sight of truth in pursuit of technical prestige. Postman saw television reduce every message—whether politics, religion, or science—to a spectacle.

-

Both believed that memory, to matter, must be reanimated. For Schiller, social memory must be infused with moral vitality or it becomes dead weight. For Postman, education must be rooted in asking why, not just how.

-

Both distrusted the idea of automatic progress. Schiller refused to believe civilization made man better; it merely dressed him better. Postman saw that new tools don’t make us wiser—they just amplify whatever wisdom or foolishness we already possess.

And in both, we find this unspoken plea: that we stop confusing knowledge with wisdom, speed with insight, novelty with meaning.

Where Are We Now?

Today, Schiller’s Tantalus has grown more agile, more connected, and more lost.

He carries a phone that gives him access to more information than the Library of Alexandria. He lives in a world where AI can write sonnets, cure diseases, and flood a country with propaganda in the same breath. He moves faster, learns faster, but changes more slowly. His feet are still in the mud.

He scrolls endlessly through fruit that flashes, dazzles, enrages—and explodes. What he consumes nourishes almost nothing. What he wants is always just out of reach. There is no oracle to consult now, no underworld pilgrimage to shake him awake. Only a world moving faster than his capacity to reflect.

We are Tantalus, surrounded by miracles and unable to use them wisely. We are Postman’s citizens, amused to death and algorithmically distracted. We are Schiller’s students, reciting formulas we no longer believe, defending institutions that have forgotten what they were built to do.

The Path Still Open

But neither Schiller nor Postman wrote to despair. They wrote to warn.

And their warnings are valuable because they are humanist at heart. They do not ask us to abandon technology or memory or institutions. They ask us to reclaim them. To remember that wisdom must be lived, not stored. That memory must be chosen, not just preserved. That institutions must be judged not by their longevity, but by the vitality they offer to the living.

In Schiller’s dream, Tantalus cannot break through the barrier of bones. He cannot drink from the Elixir of Life. But he is not alone. The dreamer—Schiller himself—enters the myth and tries to help. He looks for stones to break the fence. He considers climbing the tree.

That is the task Schiller offers us now, a hundred years later: to stop walking in circles and start climbing again. Not toward infinite information, but toward understanding. Not to conquer the world, but to live wisely within it.

The fruit is still there. But so is the choice.

Suggested Reading

-

F.C.S. Schiller, Tantalus, or The Future of Man (1926)

-

Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985)

-

Neil Postman, Technopoly (1992)

-

Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society (1971)

-

Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (1932)

-

Marshall McLuhan, The Medium is the Message (1967)

- Bertrand Russell, The Impact of Science on Society (1953)

Beezone, a non-profit educational archive and library. Beezone library centers on culture, consciousness, and spiritual transmission at the intersection of history and myth.

This interview between C-SPAN’s Brian Lamb and Neil Postman—centered on Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death—was filmed in 1988, just as personal computing was beginning to emerge and long before the internet transformed the media landscape.

As you watch, keep in mind the historical moment: television was still the dominant medium shaping public discourse, but the digital revolution was on the horizon. Postman’s insights into the nature of media, spectacle, and the erosion of rational discourse feel eerily prescient today.

To bring his critique into the present, simply substitute “television” with “the internet”—or more specifically, with today’s social media platforms, algorithm-driven news feeds, and entertainment-saturated digital culture. The core argument remains: when a culture’s primary mode of communication prioritizes amusement over substance, the consequences for public life, education, and democracy are profound.- Beezone