William Blake His Philosophy and Symbols

William Blake His Philosophy and Symbols

by S. Foster Damon

Constable and Company LTD

London Bombay sydney

1924

Introduction

THIS book is an attempt to give a rational explanation of Blake’s obvious obscurities, and to provide a firm basis for the understanding of his philosophy. The public has been baffled so long with hints of mysteries and madnesses ,that it has come to regard Blake’s work as too eccentric and remote to repay personal investigation. This attitude is completely wrong. Blake’s thought was of the clearest and deepest ; his poetry of the subtlest and strongest ; his painting of the highest and most luminous. He tried to solve problems which concern us all, and his answers to them are such as to place him among the greatest thinkers of several centuries.

The attitude of modern criticism towards Blake to-day is analogous to its attitude towards Beethoven not so long ago. The world at large then admitted that Beethoven had written many charming things in his younger days ; but that his last twenty years were matters for the maddest enthusiasts only. The poor man’s complete deafness had cut him off so entirely from humanity, that theory overcame him : he was carried to the clouds by his hippo-griff ; and whatever transcendental heaven he wished to express , the human ear was physically incapable of supporting his harmonic monstrosities.

And so with Blake. The Songs of Innocence are read everywhere ; yet we lack a correct text of The Four Zoas! The lyrics are in every anthology ; yet pros of literature wonder if the are worth reading!

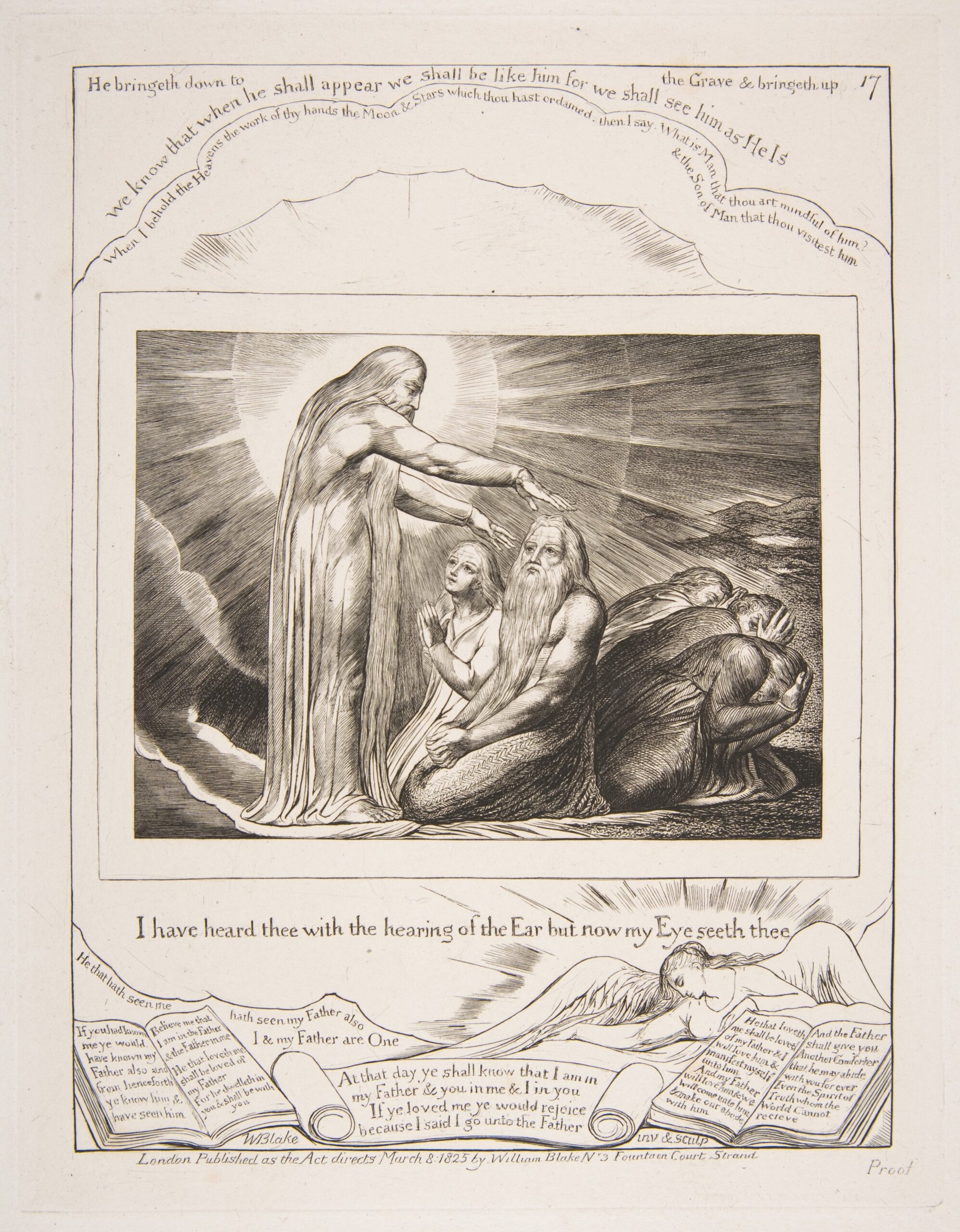

I confess frankly what when I began collecting comments on Blake, I thought him mad and the Jerusalem trash. Butas the work went on, and plane after plane of sanity was opened , my conversion began . Now I firmly believe that the last of Blake’s works are his greatest ; that the Jerusalem ranks with its contemporary, the Inventions to Job.

Neither taste nor opinion, however, is basis for criticism. The only possible method of judging is to find out to find out, first, what the man tried to do ; secondly, whether or not he did it ; after which, in a mere coda , we may venture our individual decisions as to whether or not it was worth doing.

Blake was trying to do what every mystic tries to do. He was trying to rationalize the Divine (‘to justify the ways of God to men’), and to apotheosize the Human. He was trying to lay bare the fundamental errors which are the cause of misery . These errors he sought, not in codes of ethic, nor in the construction of society, but in the human soul itself.

It is the fashion among a few enthusiasts to compare Blake with Shakespeare. The absurdity is obvious. Great, men can seldom be compared . Nevertheless, the two curiously together Blake was the complement Shakespeare. The Elizabethan recorded all the types humanity but one the mystic the Georgian recorded no other but the mystic. One saw individuals everywhere the other saw Man. The first hardly systematized human problems he beheld situation only to whose solution he gave no clue; the second saw problems everywhere, to solved by Reason under the guidance of Inspiration. One hid himself, and identified himself so well with his creations that we can hardly say what Shakespeare was like ; while from Blake’s writings we could reconstruct his very features. Shakespeare found our life a dream rounded by the sleep of death ; Blake found our life a dream to be followed by a more glorious awakening than we can possibly imagine. Both were poets who translated everything in to the terms of humanity .

And here lies the root of Blake’s greatness . His feet stride from mountain to mountain ; and if his head is lost among stars and clouds, it is only because he is a giant. His heaven is no abstract of metaphysics ; it is a map which charts the soul of every living individual . His God is not some dim and awful Principle ; he is a Friend who descends and raises Man till Man himself is a God. And by this dealing in universals Blake came to that point where such diverse temperaments as Milton , Fra Angelico, Nietzsche, El Greco, Paracelsus, Shelley, Michelangelo, and Walt Whitman may be invoked for fair comparisons. It is in a way not a bad sign of Blake’s greatness that so many dissimilar sects claim him the Revolutionaries , the Theosophists, the Vers Librists and their opponents, the Spiritists, and so on. We can treat of Blake as an Alchemist. There have been prominent Catholics who have welcomed many doctrines of this hater of priests!

But I have wandered far from my thesis. What Blake tried to do I have briefly described; whether it was worth doing, we need not say. Whether he did it just there is the centre of the critical vortex.

For Blake did not believe in unveiling the Truth completely. He always held something in reserve . He not only cried to mankind to put on intellect ‘ ; he made that faculty necessary if his works are to be understood. There never was a greater intellectual snob. He elaborated a marvelously woven veil for his Sanctuary, so heavy that none has moved it very effectually, so beautiful that none has refused some genuflection.

This was not due to cowardice or caution. When Blake spoke out, none could be bolder than he. Nobody in his own age approached him for boldness. Even now, we who recognize his purity hardly dare repeat some of his doctrines. There are poems printed with the asterisks of prudery ; there are drawings which have not been reproduced nor even described. We admit our own silliness, yet we lack courage , even after this lapse of a century and more, to repeat Blake’s own words, safely dead as he is.