By Sandy Bonder and Tony Montano Krishnamurti tells people to think, and they start

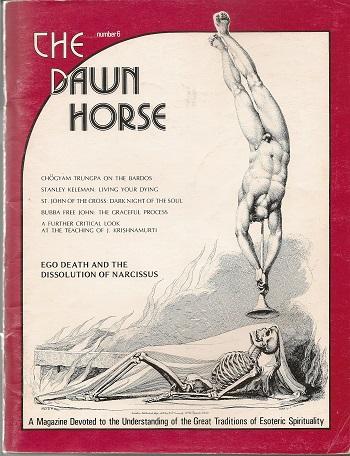

believing immediately. – Bubba Free John The last issue of The Dawn Horse (No. 5) included a

short article by Bubba Free John, “On

the Teaching of ]. Krishnamurti.”

Essentially, this was Bubba’s brief and characteristically

exaggerated response to the often repeated suggestion that

what he teaches is the same thing Krishnamurti teaches. His

remarks there were probably not -entirely comprehensible to

someone who is either unfamiliar with Bubba’s own work or

personally attached to Krishnamurti s work. The article was

not fundamentally a criicism of Krishnamurti himself or the

content of some of his best statements, but rather of his

teaching as a whole and as a living event. It was

principally a criticism of how others tend to understand and

use Krishnamurti’s statements and considerations. In any case, the article prompted a flurry of

responses and reactions, some of them quite shrill and

vehement. Of the several letters we have received, we have

printed a single representative below, one which voices the

major arguments that have been brought forward. Following

that is our own response, with lengthy quotes from Bubba’s

recent talks and writings, which we hope will clarify

matters generally as well as address the specific objections

raised in the letter. We hope to show, among other things,

that Bubba’s apparently severe appraisal in the first

article was not an ill-conceived string of epithets, but a

humorous, strongly worded but nonetheless accurate picture

of J. Krishnamurti’s teaching work. To the Editors (August 9, 1975): Re: “On the Teaching of J. Krishnamurti” by Bubba Free

John in issue No. 5 of The Dawn Horse. It always

distresses me when one great teacher attempts to belittle

the intent of another, as is the case I think in this

article. (On the other hand, it must be said that

Krishnamurti has never had one good thing to say about

“gurus” either individually or collectively.) It always

puzzles me why “egoless men” engage in intra-fraternity

snubbing. Why aren’t they rejoicing together in their common

effort to elucidate the Dharma? I do not think it increases the stature of Bubba Free

John or enhances his own teaching to refer to Krishnamurti’s

teaching as “adolescent philosophizing” that attracts “the

most mediocre and sophomoric inclinations in men” by “method

and trickery.” The depth of Krishnamurti’s teaching has been

respectfully acknowledged world over by men the caliber of

Aldous Huxley, Rollo May, and Alan Watts. Also, Bubba’s article contains many inaccuracies or

misstatements of facts concerning Krishnamurti’s teachings.

Krishnamurti never advocated pursuing “the quiet mind” or

any kind of “meditative state” as Bubba suggests. Bubba

states, “It relies on a form of attention that is methodical

or deliberate and certainly oriented toward a specific

goal.” Krishnamurti takes great pains so that people will

not so misinterpret his teaching on “choiceless awareness.”

And I’m sure that Krishnamurti himself would vehemently deny

that his way “pursues a change of state as a specific

exercise.” Is it accurate to characterize Krishnamurti’s teaching as

a “mind dharma”? Do the following statements of Krishnamurti

(from his book Freedom from the Known) suggest this,

and in fact could they not have been made by Bubba

himself? I can observe myself only in relationship because all of

life is relationship. ‘Understanding is not an intellectual process. A man who does not know what passion is will never know

love because love can come into being only when there is

total self-abandonment. Control in any form, like suppression, produces only

conflict. It is not discipline first and then freedom; freedom is

at the very beginning, not at the end. … a living mind is a mind that has no center and

therefore no space and time. Such a mind is limitless and

that is the only truth, that is the only reality. Greg Treleaven Ojai, California Dawn Horse Press Response One of the most common notions in the current “spiritual”

scene is the idea that, “because we’re all one,” there

should be no conflict between different teachings, no mutual

criticism, and no controversy whatsoever. This idea is mere

sentiment. It reflects no genuine understanding of what real

“oneness” or non-separation is about, and only provides

people with a way to become vague, and insulated from the

real spiritual process. Thus, when we are confronted by a

critical stand-off between different teachers, we interpret

it as personal “snubbing” and one-upsmanship and try to

mediate some kind of reconciliation, rather than allowing

the force of these criticisms to undermine our own false

notions, prejudices, and assumptions. In fact, such critical work has always been an integral

part of the elaboration of the Dharma of Truth among men.

Such apparent conflict is necessary to serve the awakening

of real understanding in men. In the great esoteric

traditions many communications, both secular and spiritual,

have always been criticized from a fresh point of view. This

is not a form of conventional warfare. It is not the

expression of childish animosities and jealousies. Rather it

is the expression of the continual refreshment of the way of

Truth. The Dharma is always a purifying influence, and part

of its manifestation through any human Guru is the criticism

of whatever other communications are influential in that

time and place. Anyone who reads the history of human

spirituality must realize that this is so. Look at the

public work of Jesus and Gautama, of the Zen Patriarchs, of

other Siddhas like Shankara, Milarepa, Kabir, Tukaram,

Ramakrishna, Ramana Maharshi. Such mutual criticism is not a

game directed toward harming or upsetting people, but it may

be interpreted as such by those who are not sensitive to its

real usefulness. All distress at apparent conflict between

spiritual teachers only reflects the desire to escape or

suppress the dilemma, suffering, and conflict at the core of

life, rather than to understand it. Those who do understand

are capable of very dramatic disagreements in human terms,

and this does not in anyway impair or conflict with their

conscious and radical non-separation from all beings.

“Dharma combat” between truly “egoless men” is no less a

form of their rejoicing than a shared cup of tea, or an

embrace. Bubba’s article on Krishnamurti’s teaching was itself a

response to many communications we have received, even from

those entering The Dawn Horse Communion, which assume a

basic equation between the two teachings. It was neither a

personal attack, nor a hasty putdown pulled out of the air.

Bubba felt it necessary to clarify the differences between

his work and Krishnamurti’s because people do not seem to

recognize that they involve utterly different assumptions

and forms of instruction and practice. Mr. Treleaven himself

points to perhaps the basic difference in his parenthesis

about Krishnamurti’s dismissal of the Guru tradition. That

is the aspect of his influence that demands the most

decisive criticism, because it ultimately undermines the

entire spiritual process among men. On the basis of this

distinction alone, it must be seen that there is no equation

to be made between Krishnamurti’s teaching and that of Bubba

Free John. As Bubba said in his article, that should be

obvious to anyone who has read and to some degree understood

his written works. Satsang, the relationship to the real

Guru, one who is alive as very Reality, is the principle,

the means, and even the ultimate realization of the way of

understanding. But in Krishnamurti’s work, Satsang is

denied, the Guru is denied, and Reality or Truth is thus

reduced to a passive function, dependent for its

manifestation upon the mechanisms of the human mind (or

their breakdown). Some of the letters we have received have argued that in

fact Krishnamurti’s discourses, books, and contacts with

others cannot in fact be considered a teaching, because he

claims no authority for himself and consistently refuses to

allow people (at least in public conversations) to relate to

him as a guru or teacher. Furthermore, he denounces all

other forms of authoritative teaching that men have engaged

in, both past and present, as useless, misleading, and

mutually destructive. Because he says all this, people

assume Krishnamurti is somehow not a teacher, and that they

certainly are not his followers. But all that is a lot of

semantics. Obviously he is a teacher! He represents

precisely the type of human activity and posture that we

call “teacher,” “teaching,” and “authority.” He invites

people to come to his discourses, he writes or supervises

the editing of his books, he has a large following, schools,

foundations, etc., all dedicated to the promulgation of his

particular point of view. There is something specific that

he represents, that he communicates more or less

repetitively, and people are expected to relate to it as a

verbal communication. What Krishnamurti is saying, then,

with his condemnation of the teacher-disciple game, is

something entirely different from what it appears to be on

the surface, and what so many people accept it to be. Bubba

Free John recently commented on all this in a taped

discussion: All he is saying, really, is that if you are going to

somebody for the sake of illumination, there is a right way

and wrong way to do it. Otherwise he would never say

anything. He would keep himself in a closet! He is

suggesting the right way is not to consider someone as an

authority, like the Pope, and believe because it is dogma

and must be believed, but to consider it. He wants his

listeners to consider his argument for themselves. Not

simply to consider him a source of Truth, but to consider

what he is saying. Well, true enough! That is a very simple

statement. What’s the big deal? I don’t really know of any

spiritual teacher who asks people to do anything different.

I don’t even know of fakes who ask people to do anything

different. What he means is that you should have a proper

and intelligent relationship to what he says, and that is

all. However, Krishnamurti communicates his opinions in

such a way that, for ordinary people, they seem to imply

judgments of a negative variety on all kinds of teachings,

teachers, spiritual processes, etc., prior to any kind of

comprehension of what they are up to. It is a sort of

blanket rejection. That kind of opinion is clearly contained

throughout his writing, so the people who simply accept his

statements assume that any Guru, or any spiritual process

other than purely considering some mental argument in

yourself, is completely unnecessary. In fact, it is to the verbal arguments, the verbal

teachings, the sayings and philosophy of individuals past

and present that Krishnamurti directs himself critically. He

does not direct himself to the spiritual process,

fundamentally. When he is talking about following an

authority, he is talking about an academic authority, a

philosopher who has a verbal communication for you to

consider or believe. Well, to dismiss some Siddha as an authority is beside

the point. As an authority, even a Siddha-Guru is not worth

any more than an old pair of shoes, relative to the Truth.

It is not as authorities that the Siddhas are the Guru in

Truth. Just so, the Dharma of Truth is not to be valued

because it is authoritative. It is valued by those who turn

to it for the same reasons that Krishnamurti’s teaching is

valued by those who turn to it. People who truly take on the

form of spiritual life do so not because of the garbage in

their minds, nor because it is spoken by an authority, nor

because it is authoritative in its tone, but because they

have considered the argument in their own terms. What is Krishnamurti doing other than directing

people’s attention toward various things of the mind,

getting them to consider what he says in various ways, to

assume a certain relationship to it, to abandon it or take

hold of it? He is performing a conventional teaching role

and, in that sense, has followers. He does not represent the

great Guru-function of the Siddhas, or even of conventional

spiritual masters, yogis, saints, and so forth. He does not

have that function in any sense. He does not assume it and

does not direct himself toward it. But people assume that he

does. They make generalized assumptions about him as if he

were talking about all of these things, whereas

fundamentally he is directing himself toward things of the

mind, toward philosophy, teachings, and so forth as things

of the mind, and to following or not following as things of

the mind. This gets us into a second important area of distinction

between Bubba Free John’s and Krishnamurti’s teachings: the

specific prescriptions, instructions, or methods for

spiritual practice or sadhana. Here again Krishnamurti and

his defenders insist that he offers no method and asks

people to pursue no goal, etc. Certainly Krishnamurti

recommends no specific or obvious method in the sense of

saying, “Do this and you will realize that.” He wants to

avoid the kind of language that people conventionally get

involved with in spiritual undertakings of this order, in

which they are motivated to attain something specific.

However, if you take his recorded teachings together, you

can clearly find a cycle of argument or a pattern of

consideration that is repeated. His emphasis is on specific

attention to the movements of the mind in order to undo the

limitation of thought. Clearly there is a distinction to he

made between reciting a mantra in order to gain a certain

state of mind, and the more sophisticated consideration

Krishnamurti is speaking of. But that does not make it an

altogether different sort of thing. He still offers his

listeners a conventional and fundamentally methodical

approach to life. It is just that his approach is not

mystical. It has nothing to do with the subtle body, with

subtle dimensions, with areas of conventional siddhi of a

cosmic or mystical variety. Krishnamurti is speaking about a

kind of realization that occurs in life, in the gross

dimension, through consideration of the things of the

mind. The method that Krishnamurti recommends to his listeners

is, as Bubba described it in his article, a process of

examination and insight, a serious investigation of the

functions of cognition and perception at the level of the

mind. To be sure, Krishnamurti does not explicitly advocate

pursuit of “the quiet mind,” attainment of a “meditative

state,” or deliberate adoption of goal-oriented

methodologies. The forms of motivation, seeking, and

goal-orientation in his path are much more sophisticated

than that. His verbal teaching seems paradoxical in this

respect. It is not so easy to pin down. But if you examine

how it is enacted as a living process among men, its

fundamental character becomes obvious. It is for this

reason, by the way, that criticism of dharmas must sometimes

take on what seems to be a personal quality. No teaching

occurs in a vacuum, an abstract, philosophical realm of

truths. To criticize Krishnamurti’s teaching fully, it is

necessary to enquire also as to how it is lived, not only by

Krishnamurti but by his followers as well. The whole process is epitomized by Krishnamurti’s

favorite form of teaching: the sit-down lecture and

question/answer session. Here he best serves to catalyze a

process of self-examination in his listeners. Through this,

he offers hope for the penetration of conventional

“stupidity,’ the seeing of “what is,” and that is

liberation. Naturally, when they respond to Krishnamurti’s

communication, people try to see what they are doing-they

look at their thoughts, feelings, and images, their

reactivity. Krishnamurti talks about fundamental insight and

liberation, but how is it brought about? Thus, Bubba asked,

“What Siddhi does he represent among friends? What sadhana

does he recommend?” No teacher can finally serve anyone’s

real transformation by asking him to sit down and engage in

consideration of a conceptual argument exclusively. Nor is

it served by adoption of an investigation of one’s mental

conflicts, etc., as an ongoing activity. Such a process is

superficial – not in the sense of being flip and silly, but

in the literal sense. Much as he disparages thought,

Krishnamurti is fundamentally asking people to think! He

does not require them to do anything at any level other than

the mind. He tells them that real “seeing what is” cannot be

sought or accomplished through any kind of effort. What else

can he be asking of them, then, but to think it over – to

consider his argument in themselves, and allow its merit to

show in their own minds? Under such circumstances, what can his listeners do but

seek a change of state, even no-seeking itself? If the

process is truly in their hands alone, how can it be

anything but deliberate and goal-oriented? How can they help

but be impressed with images of the “quiet mind” he speaks

of, and how can they help but look for “choiceless

awareness”? The process initiated in relationship to a genuine

Guru requires participation in an utterly different process.

Bubba has also clarified this recently: The process involved with the true Guru, the

Siddha-Guru, is not this one of just considering the things

of the mind. There is a conventional and minimal aspect of

any spiritual process in which there is consideration of the

things of the mind in this way – sitting down and

considering what is said, considering it in yourself-but

that is not fundamentally what the process is that is

communicated in the company of the Guru. The kind of

involvement that is required of a person in this process of

Satsang is total life-involvement. The Guru demands your

life! It is not a process in which people do things to the

body and mind in order to attain various states. It is one

wherein the totality of a person’s existence is brought into

a functional condition that serves the crisis of

consciousness by reflecting all this content in disarming

ways, in situations in which the individual has no arms, no

methods, no philosophy, no spiritual practice to distract

him. In other words, the Guru does not merely ask people to

consider his argument (though that is certainly part of his

teaching work). He also takes them “by the neck,” requires

them to surrender every moment to him in the most practical,

functional ways, and deals with them face to face over time.

He demands their life-level participation in an ongoing

process. And at the foundation of all these demands and

disarming confrontations is the grace manifested in the true

Guru: the Siddhi or Conscious Power of the Divine. This

Siddhi is not some remarkable psychic capacity, or an

authority-conferring form of subtle knowledge or energy. It

is living, unspeakable, absolute Truth. This is what the Guru brings to his devotees

through his mere presence, and he is always “pressing it

upon them with more and more intensity, always to the degree

just beyond their preferred tolerance.” As long as they

cleave to the Guru’s practical demands and maintain

themselves in his presence and Community, the Divine

Presence that he perfectly communicates will literally

manifest in them as them, with the force of intelligence

that precedes the conventional and lower mind. It involves,

on the fundamental level of consciousness, a more and more

inclusive comprehension of one’s whole life of strategic

suffering, to the point of direct intuition of Truth, and

ultimately perfect dissolution in that same absolute

Consciousness. Secondarily, through the “yogic” aspect of

the Guru-Siddhi, the way of understanding involves thorough

transformation and harmonization of one’s life functions,

gross, subtle, and causal. All this is initiated through the

humorous agency of Grace, and is fulfilled through absolute

responsibility in the devotee. Lacking Divine Grace and living responsibility, a path

like Krishnamurti’s amounts to an aesthetic cleaning out of

the head. But even that is not always the case. In a recent

essay, intended to elaborate on his original article, Bubba

Free John appraised the effects of Krishnamurti’s teaching

work on others: DEVOTEE: J. Krishnamurti says, “No Guru is

necessary.” MAHARSHI: How did he know it? One can say so after

realising, but not before. – Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi Krishnamurti’s talks contain many descriptions and

considerations that seem possibly true of realization. Thus,

the hearer may imagine that, if he comprehends or enjoys

sympathy with these statements and considerations to some

immediate and profound degree, he is in fact enjoying

realization. Therefore, he imagines the Guru and the process

of life-obliging sadhana are either false or unnecessary for

him. And he leaves the lecture hall full of the ego of

liberation, imagining God, Guru, Self, and sadhana to be

anachronisms in his pure comprehension. His adolescent

search for independence has been justified and fulfilled.

But such a little thing has happened. Krishnamurti convinces people that authorities, methods,

effort, belief, goals, all such things are false and

unnecessary. And so they imagine, on the basis of that

conviction, that they are free of all of that. It is not so.

In the case of realization such confessions may be true in

one’s own case, but prior to that the individual is

compulsively bound to the ritual limitation of existence.

Therefore, in spite of their best conceptions, individuals

always re-create authorities, methods, efforts, beliefs,

goals, and all the rest. For this reason, those who are most

convinced by Krishnamurti make him an authority; they make

his teaching a method, an instrumental consolation, and all

their comprehension becomes a source of righteousness with

which they are preoccupied to the point of satisfying their

felt need for immunity and no change. Such people have a

dogma to undermine their own effort and to defend themselves

against the processes that would truly undermine their

suffering and ignorance. They are true believers and ardent

seekers, even though they disavow every symbol in the

mind. Until there is realization, there is no realization.

Krishnamurti may do a service if he leads a man to see that

in fact he is committed to suffering and limitation. Then

such a one may become available to the real process of

sadhana and live it. But the usual man who stands on

Krishnamurti’s arguments has only become enamored of one of

the many idols or consoling solutions that distract men from

the way of Divine Realization, the way of perfect Sacrifice

or Radiant Bliss. Krishnamurti’s apparently revolutionary statements and

considerations may in some sense represent the wisdom of his

own realization, but they do not become realization in

others through mere hearing. Rather, they function as

conventional, ego-supporting concepts for his hearers, and,

as such, serve only to prevent the responsible and

sacrificial process of their real transformation. How much

wisdom is reflected in one’s speech if there is no

accounting for the condition of the listener? Krishnamurti

is willing to argue with any fool in a theatre, but he will

not live with that fool and serve him until he becomes truly

wise. If we separate his public work and influence out from

the whole affair of spiritual life and realization, then its

value as a philosophical criticism of certain conventions of

personal and social life may be seen. But once it is assumed

that listening to Krishnamurti and considering his words is

itself a kind of spiritual or perfect activity, there is the

beginning of the kind of little theatre in which the

stupidity and separativeness of men is so clearly

demonstrated. People quickly realize that the philosophically quiet

mind is of no consequence whatsoever at the point of

terrible death. Nor, if they are sensitive, will they be

consoled by such at the point of terrible life. Not that

radical understanding, as described by Bubba Free John,

provides some form of consolation in life or death, either.

It is only what it is: radical, humorous, free comprehension

of all events that arise in consciousness. Initiated, again,

by Grace, and maintained as one’s own presence in the midst

of all events and forms arising as life and world, such

understanding is absolutely free of the strategic reaction,

or non-reaction, to one’s own dilemma that Krishnamurti

requires in all those who come to hear him out.* It is easy to pick out a few quotes from Krishnamurti

that make him sound as if he were talking about radical

understanding. You can find pieces of anyone’s writing that

correspond to almost anyone else’s teaching, and that

correspond to great archetypal statements that all teachers

have always made. This is not the point at all. What we want

to get down to is what Krishnamurti’s communication

represents for others; what kind of relationship they take

to it, or are asked to take to it (which may be two

different things); what it involves as a process for them,

how it affects their lives-in other words, how it engages

them on an ongoing basis from day to day. That is the point.

All the comparisons by finding fragments that are parallel

are completely beside the point. This present article, along with Bubba Free John’s

original essay in the last issue of The Dawn Horse, should

clarify the distinction between the two teachings as living

events. When Bubba describes Krishnamurti’s work as

“adolescent philosophizing,” he is not throwing out petty

and glib putdowns. On the contrary, he is referring

precisely to the serious, heavy, “meaningful” discussions

that Krishnamurti presents to people. All this is adolescent

in the most specific, comprehensive, and critical sense of

the term: It is an effort to assert and maintain a posture

of freedom or independence in the midst of life, on the

basis of mere mental conviction. That point of view, and the

image of personal fulfillment it represents, are exactly

“the most mediocre and sophomoric inclinations in men.” Such

adolescent, separative striving is the very symbol of modern

man, and in contemporary spirituality it is epitomized by

the teachings of Krishnamurti. To try to become free of the

suffering at the core of your life by arbitrarily

investigating it in such a way that you do not seek but

somehow spontaneously discover “choiceless awareness” is

truly to be taken in by a form of “trickery.” There is no

real transforming process, but only the consoling prospect

of an extremely persuasive, honorable, and heroic

undertaking. It is literally better to be “cooked alive,” as

Bubba wrote, than to continue your life in such humorless

immunity. What Krishnamurti means by “freedom” is not

radical, absolutely non-separate humor, a perfect esoteric

dissolution in the Divine, in which al’. Wisdom is shown.

Rather, it is an exalted form of subjectivity-an apparently

limitless mind, perhaps, but even that is not Truth. Truth

is Absolute, Only God. Thus, none of this communication from mind to mind is

serious. However useful, annoying, right or wrong any

criticism may be, it is not ultimately significant. It is

better to be happy. But we cannot be really happy if we are

not also intelligent. Bubba Free John recently expressed it

very simply: Rejoice in the Dharma in the community of your own

practice. Rejoice in God in the company of all men of humor

and love. As for the rest, be watchful, manly, and without

illusions. *lt is not possible, in such a brief

article, to communicate the fullness of the nature and

process of understanding in Satsang with the Guru. For a

better appreciation, please consider Bubba Free John’s

Teaching as a whole, to be found in his three major works

(The Knee of Listening, The Method of the Siddk.zs and

Garbage and the Goddess), his essays and talks in this and

other issues of The Dawn Horse, and other publications of

The Dawn Horse Communion.