“This may be the right moment for having a look at ‘the oriental background* against which the whole of Greek culture had arisen”

“(The) oral tradition, began to lose its importance.”

History of Classical Scholarship

From the beginning to the End of the Hellenistic Age

Rudolf Carl Franz Otto Pfeiffer

Rudolf Pfeiffer (20 September 1889 – 5 May 1979). Image courtesy of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. – Professor of Greek at Hamburg (1923) and Freiburg (1928) Universities, then Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford from 1938-1951.

![]()

The following is from Chapter II, pp. 16-32

THE SOPHISTS, THEIR

CONTEMPORARIES, AND PUPILS

IN THE FIFTH AND FOURTH CENTURIES

The Sophistic movement of the fifth century holds a unique position in the history of the ancient world; it never repeated itself, and, in a historical sense, one should not speak of a ‘second Sophistic’ in Roman times. The part it played in the early history (or prehistory) of classical scholarship was an intermediary one. The Sophists were linked with the past in so far as they developed their ideas out of hints in earlier literature ; so we have always to look back to poetry as well as to philosophy and history. On the other hand, they were the first to influence by their theories not only prose writing, rhetoric, and dialectic above all, but also contemporary and later poetry; so they force us to look ahead.

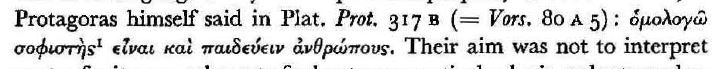

The Sophists can be regarded, in a sense, as the heirs of the rhapsodes. They also came from every part of the Hellenic world and wandered through all the Greek-speaking lands; but in the age after the expulsion of the tyrants and the defeat of tire Persian invader their ways quite naturally converged on Athens, the leading democratic city-state, where they could gather their best pupils around them. The Sophists explained epic and archaic poetry, combining their interpretations with linguistic observations, definitions, and classifications on the lines laid down by previous philosophers; but their interest in Homeric or lyric poetry as well as in language always had a practical purpose, ‘to educate men’, as

poetry for its own sake or to find out grammatical rules in order to understand the structure of language. They aimed at correctness of diction and at the correct pronunciation of the right form of the right word; the great writers of the past were to be the models from which one had to learn.

In that way they became the ancestors of the virtuosi in the literary field. If scholarship were a mere artifice, they would indeed have been its pioneers;1 for they invented and taught a number of very useful tricks and believed that such technical devices could do everything. But for this very reason they do not deserve the name of ‘scholars’—they would not even have liked it. Still less should they be termed ‘humanists’ ;2 Sophists concerned themselves not with the values that imbue man’s conduct with ‘humanitas’, but with the usefulness of their doctrine or technique for the individual man, especially in political life.

Some examples, drawn from individual aspects of their activity, will be given later; we shall look at the Sophistic practice of interpretation, analysis of language, literary criticism, antiquarian lore, and polymathy.

However, there is one of their services to future scholarship on which we have to dwell a little longer; and for that reason we take it first. The very existence of scholarship depends on the book,3 and books seem to have come into common use in the course of the fifth century, particularly as the medium for Sopliistic writings. Early Greek literature had to rely on oral tradition, it had to be recited and to be heard; even in the fifth and fourth centuries there was a strong reaction against the inevitable transition from the spoken to the written word; only the civilization of the third century can be called—and not without exaggeration— a ‘bookish’ one.4

This may be the right moment for having a look at ‘the oriental background* against which the whole of Greek culture had arisen, in so far as it is relevant for Greek scholarship. While aware of this historical process, I am, naturally enough, rather reluctant to speak of it as I have not the slightest acquaintance with the languages concerned; so I am forced to rely on the reports and interpretations of specialists and to draw conclusions from them with due reserve.

Excavations in Mesopotamia5 revealed the early existence not only ofarchives with documents on clay tablets, but also of ‘libraries’ with literary texts.

From about 2800 b.c., so we are told, the Sumerian speaking inhabitants maintained record offices as well as libraries and schools in connexion with the temples of their gods. The keepers of the clay tablets who had to preserve the precious texts attached importance to the exact wording of the originals and tried to correct mistakes of the copyists; for that reason they even compiled ‘glossaries’ of a sort. Towards the end of the third millennium Semitic invaders from the north (the Babylonians, as they were afterwards called) adopted the Sumerian methods of preservation and also made lists containing the Sumerian words and their Accadian equivalents. In the course of the second millennium the Hittites conquered large parts of Anatolia; there are cuneiform tablets found in their capital Bogaskoy showing in three parallel columns equivalent words in Hittite, Sumerian, and Accadian.1 Similar discoveries, dating from the second half of the second millennium, were made during the excavations of Ugarit (Kas-Shamra) in northern Syria. In the seventh century b.c. much of the earlier, especially the ‘Babylonian’, tradition was copied for the palace-library of the great Assyrian king Assurbanipal, who was no less proud of his writing abilities than of his conquests; there are more than 20,000 tablets and fragments in the British Museum.

His learned scribes had inherited a truly refined technique and they developed it further in the descriptive notes at the end of each tablet.2 Without romantic exaggeration we can say that these scribes felt a ‘religious’ responsibility for the correct preservation of the texts, because all of them had to be regarded as sacred in a certain sense.3 Their complicated method of ‘cataloguing’ was invented for the particular writing material, the clay tablets, and the lists of words from different languages were a product of the singular historical conditions of Mesopotamia and the surrounding countries. But no ‘scholarship’ emerged from those descriptive notes and parallel glossaries, which served only the practical needs of the archives, libraries, and schools of temples. We find much the same in other fields: the extensive oriental ‘annals’ did not lead to

a methodical writing of history’. George Sarton1 in his History of Science rightly emphasizes the importance of a controlled language for the rise of ‘Babylonian science’, which needed ‘linguistic tools of sufficient exactitude’. But it seems to be rather misleading to speak of ‘the birth of philology’2 at about 3000 b.c. Sarton, however, did not try to trace a line of descent from this oriental ‘philology’ (by which he apparently meant some sort of linguistic studies) to early Greece. On the other hand C. Wendel, in considering how technical devices for writing and for preserving the written tradition may have reached the lonians in Asia Minor, argues convincingly that they had come from the east, not from Egypt ;J but, in the present state of knowledge, one can do no more than hint at possibilities of contact. It is not unlikely that the Greek inhabitants of the west coast of Asia Minor and of the islands had been writing on animal skins before they used the Egyptian papyrus and continued to do so occasionally. Although there was literary evidence for the use of leather-rolls by oriental, especially Aramaic, scribes not only in Persia, but also in Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, and Palestine,4 actual specimens were very rare, until the Aramaic parchments of the fifth century b.c. (now in the Bodleian library’) were published in 1954.5 The statement of Herodotus (v 58) in his much-discussed ‘excursus’ (regarded sometimes even as an ‘interpolation’) is thus fully confirmed in so far as it implied that leather-rolls had been in common use in ‘barbarian’ countries; consequently we are not entitled to doubt the other part of his remark about the

to Herodotus. But he must have known another tradition from one of his main sources, Hecataeus1 of Miletus, with whom two other Milesian writers, Anaximander2 and Dionysius,3 agreed: namely that ‘before Cadmus, Danaus brought letters over’ mpd Kd8pov davadv peraKoplaat avrd (rd crrobyeia). Danaus had sailed from Egypt (not from Phoenicia) to the Argolid: the rivalry between Egypt and the Near East in this field is apparent from the beginning and persistent up to today.4 Since hundreds of clay tablets, covered with writing in the so-called Linear B Script (which had been known before only from Knossos) were found near Pylos by G. W. Blegen (1939) and in other places of the Greek mainland (Mycenae, 1950, by Alan J. B. Wace), it has been obvious that Herodotus was wrong when he expressed his opinion, although very cautiously (tij epol 8okwv}, that Greece was illiterate before the introduction of the Phoenician alphabet. The tablets are said to have been written between the fifteenth and the twelfth centuries b.c., in the late Helladic or, as Furtwangler had termed it, the Mycenaean epoch (the fullest records for Pylos are from the thirteenth century).5 We may call it the ‘Heroic age’, supposing that it was the world of the heroes whose stories we read in the Homeric poems. The surviving examples of that Mycenaean writing (at the moment more than 1,000 tablets) do not go beyond ‘lists of commodities and personnel’; there are no names of scribes, no check or alterations by a corrector as on the Accadian or Ugarit tablets we mentioned. The contents as well as the method are very primitive compared

century, can be established by a comparison of Greek inscriptions of the late eighth century b.c. with Semitic writing of this and the preceding century: similarities of letter forms show that the Phoenician model had been followed and was modified about that time.1 From the same regions of the Near East the lonians seem to have learned to prepare skins for writing material, and, as the Egyptian papyrus was called pvpAo; in Greek,2 after the city of Byblos, we may assume that it was first imported from the Phoenicians, before the foundation of Naukratis established direct contact between Egypt and Greece in the seventh century. So everything leads up to the conclusion—in the present state of our knowledge—that the introduction of letters and of papyrus dates from the early eighth or the late ninth century ;3 the route4 may have been along the south coast of Asia Minor to Rhodes.5

of the ancient world but of a great part of mankind in all ages. The Phoenician script was neither cuneiform nor strictly syllabic; it consisted of single characters, but only for the consonants. When the Greeks adopted those letter forms they took the decisive step of using them for all

the ‘elements’ of their language, which they called aro^ict,1 vowels as well as consonants. Now for the first time the quantity of the syllables and especially the structure of the quantitive verse could be displayed. A true alphabet2 had come into being. It was one of the great creations of the Greek genius; as it can now be dated to the ninth or eighth century b.c., it belongs to the epic age. For these two centuries the epic poems were representative; the Iliad and the Odyssey still reveal to us how the Greek genius became conscious of itself and found its own nature in that particular moment of its history. A new aspect of the world arose, the true Greek aspect. I used to emphasize in my lectures on Homer the important fact that the adaptation of the Phoenician characters and the final form of the great epic poems belong to the same age. That the alphabet ‘might have been invented as a notation for Greek verse’ is a rather attractive idea,3 and one wishes it could be proved; our earliest alphabetic inscriptions of the eighth century which are not all in verse,* can hardly help. But no doubt there was a new beginning, not a simple continuity from the heroic to the epic age. It is paradoxical to use a historical evaluation of the recently discovered Mycenaean writing as a basis for conclusions about a gradual inner development of Greek civilization from the thirteenth to the ninth century.5 For, on the contrary, a comparison of that syllabic script on the tablets with the earliest alphabetic writing illustrates more than anything else a ‘revolutionary’ change, a completely new start. From this new start to r&oy, the goal of

a definitive alphabetic system, must have been reached in a fairly short time. There were minor alterations and slight improvements, but there was no ‘pro-gress’ any more either in Greek or in post-Greek times.1

The pattern of development in prehistoric Greece becomes visible only against the oriental background; so we were forced to go out of our way for a little while. Now in Greece we find no guild of scribes, no caste of priests to which knowledge of writing was restricted, no sacred books’* of which the transmission was their special privilege. The Greek alphabetic

script was accessible to everyone, and in the course of time it became the common heritage of all citizens who were able to use a pen (or a brush) and to read; the availability of writing materials in early times has been mentioned already, and especially the import of papyrus from Egypt, where it had been used as far back as the third millennium in the form of smaller or larger rolls for ritual and literary purposes. So all the necessary conditions for producing Greek books were in existence from the eighth or seventh century onwards, it seems. If we try to answer the two questions in the last paragraph, we are led to distinguish four periods. There probably was first a time of merely oral composition and oral tradition of poetry. The second stage, we assume without further proof, began with the introduction of alphabetic writing. Epic poets, heirs of an ancient oral tradition, began to put down their great compositions in this new script:’ we still possess as the product of that creative epic age the two ‘Homeric’ poems. The transmission remained oral: the poets themselves and the rhapsodes that followed them recited their works to an audience; and this oral tradition was secured by the script which must have been to a certain degree under proper control. There is, so far, no evidence for book production on a large scale, for the circulation of copies, or for a reading public in the lyric age. The power of memory was unchallenged, and the tradition of poetry and early philosophy remained oral. From the history of script and book we get no support either for the legend of the Peisistratean recension of the Homeric poems or for the belief that Peisistratus and Polycrates were book collectors and founders of public libraries.

No further change is noticeable until the fifth century,2 when the third period began, one in which not only oral composition, but also oral tradition, began to lose its importance. The first sign of this is the sudden appearance of frequent references to writing and reading in poetry and art from the seventies of the fifth century onwards; the image of scribe

If we turn from the literary field to the Attic vase painters, we do not find any pictures of ‘books’ on black-figured vases; scenes of the simple life of the fldvawoi were their favourite subjects. Scenes of the cultivated life, in which representations of inscribed rolls find a place, appear first in the red-figured style, the work of the contemporaries of the tragic poets, from about 490 to 425 b.c. At least three of these paintings seem to be slightly earlier than the dated plays of Aeschylus? On half a dozen vases, letters or words of epic or lyric poems, written across the open papyrus roll, can still be deciphered? We see youths and schoolmasters reading the text; in the second half of the fifth century famous names like those of Sappho, Linos, Musaios are added to these figures. On a Carneol- Scarabaeus even a Sphinx is represented as reciting the famous riddle from an open book in her paws (about 460 b.c.).3 We are justified, I believe, in taking the coincidence of the literary passages and the vase- paintings as evidence of a change in the common use of books; no doubt it was a slow change, leading gradually to the fourth and final period, when a conscious method of rrapaSocrcs, of literary tradition by books, became established.

for the written word, and their own preference for the use of books. Such an attitude, it was argued, propagated by influential teachers, was bound to weaken or even to destroy physical memory (p,rqp.i)), on which the oral tradition of the past was based, and in the end would be a threat to true philosophy, which needs the personal intercourse of the dialectician to plant the living word in the soul of the listener. The second point may have been still more important for the future. The Socratic and Platonic arguments are the expression of a general, deeply rooted Greek aversion against the written word; they strengthened this instinctive mistrust in later ‘literary’ ages also and thus helped to promote sober ‘criticism’. The Greek spirit never became inclined to accept a tradition simply because it was written down in books. The question was asked whether it was genuine or false, and the desire remained alive to restore the original ‘spoken’ word of the ancient author when it was obscured or corrupted by a long literary transmission. If books were a danger to the human mind, the threat was at least diminished by Plato’s struggle against them; no real ‘tyranny’ of the book[1] ever established itself among the Greeks, as it did in the oriental or in the medieval world.

It remains true that their contribution to the development of the book was one general service the Sophists did for Greek civilization as a whole and for future scholarship in particular.

End of section. Page 32