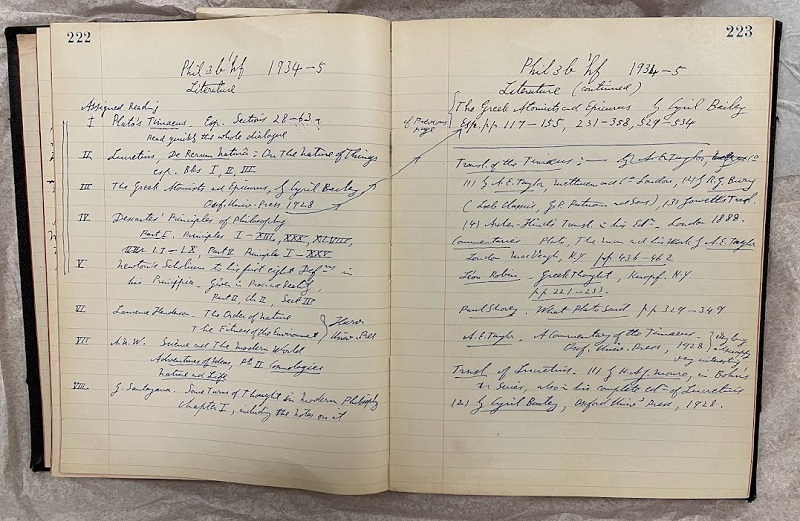

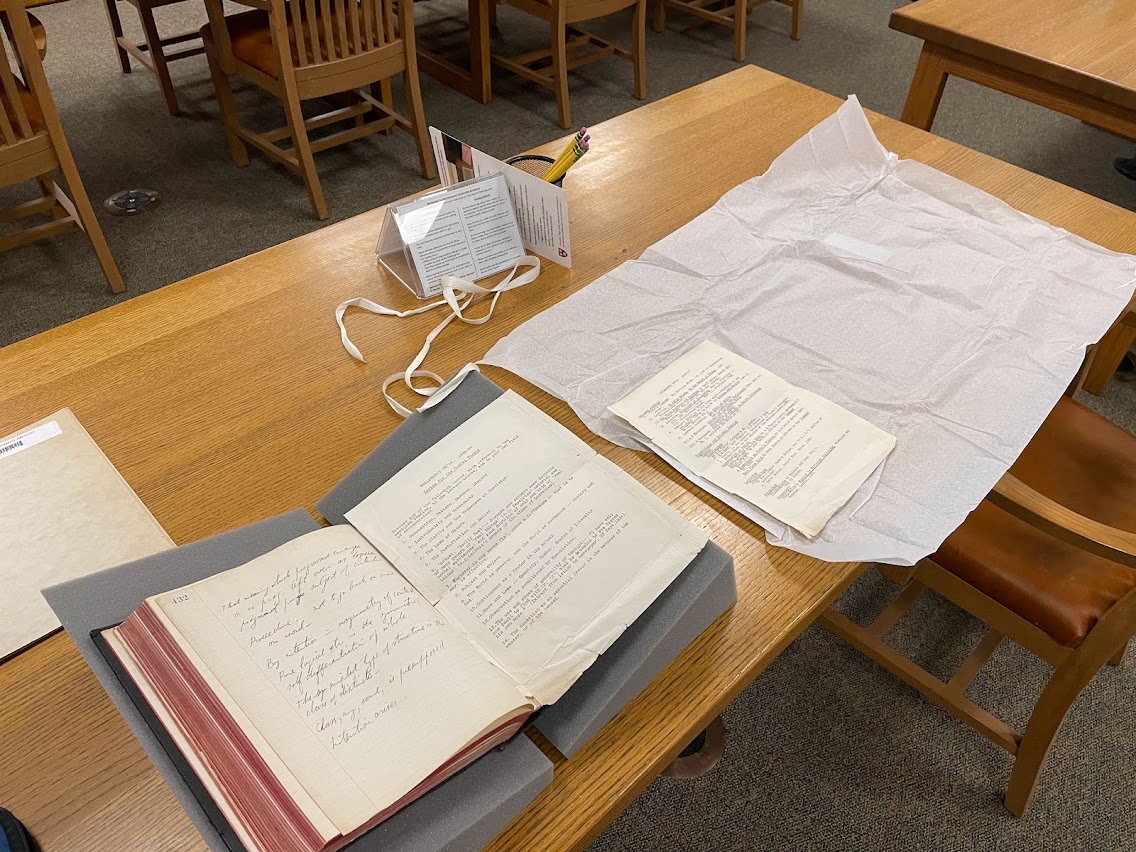

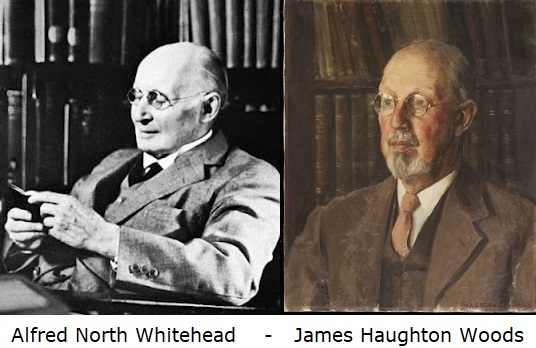

STUDENT NOTES FROM WHITEHEADS’ LECTURES ON PLATO’S FORERUNNERS

1934

complited by

Harvard Professor of the Philosophical Systems of India

II. The Beginnings of Philosophy

III. The Milesian School

IV. The Pythagoreans

- The Milesian School*

- The Milesian school was a school of thought founded in the 6th Century BC. The ideas associated with it are exemplified by three philosophers from the Ionian town of Miletus: Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes.

The theory we now hold about the origin of the Greeks is based on the excavations of Heinrich Schliemann (beginning in 1870) and later of Dorpfeld and others. These proved that a highly developed civilization existed in Crete and the Aegean Islands even before the days of Babylon. There was a long development of the Bronze Age in this region, and a distinctive art grew up more Eastern than Greek in its meticulous attention to trivial external details. Indeed this Minoan culture was in no way typically Greek. It cannot be said to have sprung from the East, but it was greatly stimulated by contacts particularly with the Hittites in Asia Minor; these in turn it undoubtedly influenced. About lO0O B.C. the Hittite Empire completely collapsed, overcome by Aryans migrating from the north. These sturdy, energetic northerners also over-ran Greece, and 1000 B.C. marks the end of a long period of invasion. The old stock was thereby invigorated and refreshed, and the flowering of Greek civilization began.

The early Greek had a strong animal nature; the Homeric heroes are embodied emotions. They were incessantly fighting, and even in peace showed a capacity for passionate feeling beyond our comprehension. This gave them great creative power. As contrasted with the people of the East, there is no love of mystery. In Homer there is a great freshness, no brooding, no secrets; he is on speaking terms with the universe. The Greeks loved clarity, and wanted to be able to transmit their ideas to each other. They loved discussion, and their cities were places where discussion was possible. They had democracy, as we have not; as in an old New England village, life was shared.

Their statues express this love of clarity; it was the typical, the essential man, not the individual man, that interested them – portraiture was a late development. This rests on the idea, to be found in Homer, that everything has its definite limit, its characteristic moment.

Thus for Socrates definition consists in finding the limits; he tends to substitute for the external panorama a teleological system, in which everything seeks to be as good a member of its class as possible. This point of view implies a conception of grades of importance, or value. The critical spirit was (wrongly translated “good sense”), the umpire between conflicting values, the perception of limits, the sense of proportion.

The Greeks were predominantly sailors; they had almost no roads, and the sea was their highway. They pursued commerce, and got certain trade routes away from the Phoenicians; but love of money was subordinate to love of knowledge.

*Compare the Eastern feeling, especially in Zen Buddhism, that the real thing is that which can’t be spoken of.

One is reminded of the Elizabethan Age. By degrees colonies sprang up, ultimately from Marseilles to the Indus and up into Crimea. These were independent cities bound by ties of religion and custom to the mother city. The first step was to set up a status of Apollo; his worship was the symbol of unity, linking the colonists with their old homes. In the sixth century B.C., these colonies, particularly the maritime cities on the coasts of Africa and Asia Minor, were more important than the mainland. The beginnings of Greek art and Greek philosophy were on the frontiers.

Miletus, capital of Ionia, was the leader. This was a prosperous port near the mouth of the Meander, shipping goods from up-river ports to the Black Sea and almost to the Atlantic. It had a thriving wool trade, and a large fleet. It had its own colonies, and a shrine at Olympia. The population was mixed, active, and unstable, consisting partly of Asiatics, partly of Athenian immigrants. Miletus, with Ephesus, Colophon, Samos, and other cities, formed the Pan Ionian League, primarily for religious, secondarily for political and commercial purposes. It is interesting to note that there were Ionian garrisons in Egypt, mercenaries of the Ptolemys.’ The city was destroyed by the Persians in 494 B.C.

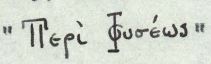

In Miletus there was a school, or group of scholars, lasting roughly from 600 to 540 B.C. This was apparently founded with the idea of promoting a more exact understanding of the principles of navigation; it passed over into disinterested investigation, prompted by intellectual curiosity rather than the desire for practical gain. The birth of European science and philosophy was in Miletus, and in the beginning the two were one. The philosophers were not mere dreamers, nor priestly figures. They appealed to reason, to impersonal verification, and attempted to explain things in terms of their causes, presuppositions, and relations. This was a new mental attitude toward the world. These men studied geography, mathematics, astronomy, and were interested in ethics as well. All used the title

for their philosophies; hence Aristotle calls them the School of Physiologists. Thales was among them.

Read the account of Thales in Burnet, and please believe in him as you would if he were a character in a novel. He was born about 625 B.C. and died about 550. We know he was alive in 585 B.C., the date of the eclipse he predicted and observed; “in this year”, says a chronicle, “lived Thales the Wise.” He was called the wisest of the Seven Wise Men, and many stories were told of him – how he fell into a well because he was watching the stars, how he cornered the oil market to show that it was easy for the philosopher to be rich if he chose, how he sacrificed an ox in his joy at solving a difficult geometrical problem (“since this time”, says Heine, “all oxen are in terror whenever a new truth is discovered.”). Once an ancient tripod was found, cast up on the shore; Apollo, speaking through the oracle, ordained that it should be given to the wisest. Thus it was presented to Thales, who modestly offered it to each of the other wise men in turn, and finally after it had gone the rounds to Apollo himself, as the wisest of all. Thales never married, since,he said, in youth he was too young, out when old, the time had passed. He warned the Milesians of the growing power of Cyrus the Persian, and was one of the instigators of the Pan-Ionian League. He is said to have spent some time in Egypt, perhaps in the Ionian garrisons, and to have learned there much about geometry and astronomy.*

*There are accounts of him in Plato (Theatetus, 174a), Aristotle (Metaphysics A.3. 983b 21, De Anima A.2. 405a 19, 5. 411a 7, De Caelo B.13. 294a 28), Diogenes Laertius i.27. 46, Herodotus i. 74, 170, Theophrastus (Dox. p. 475).

His method was to detach himself rrom personal feelings and prejudice. He kept within the natural world, sought to verify his statements, and spoke not like his predecessors in terms of fable, but in terms of reason. His motive was the disinterested desire for knowledge. Such an investigation could be called scientific, even if there were no tangible results; but Thales’ results were impressive. To help him in calculating the eclipse he probably had one of the Babylonian lists of intervals which existed at that time, but his contemporaries were none the less greatly struck and named the year for him. And he made other calculations. He made a calendar with a year of three hundred and sixty-five days instead of the lunar year; according to tradition he took the altitude of the north star, an observation useful in navigation, and said the sun was seven hundred and twenty times as large as the moon, to which it gave light.

Aristotle recounts as a rumor that Thales believed the earth, in the middle of the universe, floated like a wooden disk on the cosmic water; earthquakes were commotions in this water. He is said to have introduced geometry into Europe from Egypt as a purely theoretical science, distinct from a device for measuring fields, etc.; he saw that the visible and the geometrical line or point are not identical, that the particular triangle on the sand is not the real triangle, and that the problems of geometry are those which concern permanent and invariable relations of space.

The two formulae of Thales seem to have been, “Water is the basis of all existence,” and “Everything is full of gods.” Aristotle forces the first fragment into a construction that fits his own theory of a material cause, but this is undoubtedly a mistake. Thales does not mean “All that is is derived from the chemical H2 0”, but that in all change there is a iluid element, namely water regarded as an all-permeating soul. He is not a materialist, but a hylozoist. His water is self-moving because it is alive, as much alive as a man or a crocodile. Being alive, it transforms itself into all sorts of forms. There is no distinction between matter and mind; all matter is alive, and the power of attraction in the magnet is due to its soul. In the myths, plants, rivers, and rocks all had their conscious existences. Thus for Thales souls and things are intermingled, and everything is full of gods.

Thales’ theory of animated water may have been suggested by the incessant moving of the sea, or by the tides; indeed as late as the 18th century Laplace explained the tides as a cosmic breathing. And in the mouth of the Meander the water can be seen changing into mud; in the morning it changes into air in the form of mist, in the evening when the sun sets into fire. And plants grow out of it; as Aristotle remarks, Thales may have realized that all life requires moist nourishment. Various questions may or may not have arisen. How is the water distributed in the world, and is its bulk constant? Why doesn’t it evaporate into space? How does the water-soul shift its parts, spatially or otherwise? How did heavenly bodies and organic beings arise? Is the water-soul to be thought of as a god? Probably cosmogony did not much worry Thales, in spite of what Aristotle says.

That Thales identified the

with water is, however, accidental and unimportant. The point is that he for the rirst time conceived it to be one. Thales leaped at one bound to what might well be considered the ultimate goal of science, the reduction of all change to one term. That his solution was wrong makes little difference; his greatness lies in his statement of the problem. For a false direction may be altered, and a mistake is a spur. That the first step should be taken at all is the decisive factor. Thales is one of the great figures in the history of thought, the first European scientist and philosopher.

The idea that the

is one was accepted oy the whole school; but variations in the description of this one substance immediately began. Anaximander was a younger contemporary and an associate of Thales. Apollodorus says he was sixty-four years old in b47 B.C., and that he died soon after; so he must have Oeen born in 611 B.C. He was the first person in Europe to write a book on science, and probably the rirst writer of Greek prose. He made the first map; and invented the gnomon, a kind of annual sun-dial, which indicated the solstices and equinoxes by means of the shadow cast by an upright on a series of concentric circles surrounding it. He discovered the obliquity of the zodiac. Nothing is known of his personal life.

Anaximander was not satisfied with Thales’ water, for the source of change can’t be one of the changing things. Nor can it be limited; the one substance which is to make the origin and growth of things thinkable must be such that the originating process shall not cease. He used the word

for the initial term in the series of changes (Theophrastus says he was the first to do so); this means more than origin or beginning – it is the first or ultimate principle, that permanent and unchanging reality “which encompasses and rules all.” Another name for it is

best translated the Indefinite or the Unlimited.

is boundless in dimensions, time, and qualities, matter, though not the matter of sensuous experience. It is eternal impulse to motion, inexhaustible vitality.

is boundless in dimensions, time, and qualities, matter, though not the matter of sensuous experience. It is eternal impulse to motion, inexhaustible vitality.

The result of the impulse is a kind of sifting movement; and opposites are shaken out. These opposites are contrasted forms of change, relatively lasting tendencies. The primary opposites are fire and cold. The former is less shaken, and remains intact on the periphery. The latter is drawn to the center and separates into earth, water, and air. The earth, a half-fluid core gradually solidified under the influence of fire, is a round olock like the drum of a pillar, one-third as high as it is thick; it rests on nothing, but is balanced by the contending strains of fire and cold. As the fire continues to contract the central cold, the air expands. Penned in between water and fire, it bursts through the shell which divides the sphere of fire from the sphere of cold in huge rings or wheels, fragments of fire enveloped in air. These are the heavenly bodies; they show themselves through holes in the air at some point in their circumference, through which the fire spurts as from a bellows.[*]

[*]This interpretation does not emerge clearly from the notes, which sometimes make it seem that the fire spurts through the holes in the shell. This would leave day and night unexplained, and the revolving wheels without meaning. I nave slightly amplified the notes (and perhaps twisted them) by adopting Burnet’s interpretation.

The revolution of the wheels makes aay and night; eclipses are the blocking of the holes; the seasons are caused by the nearness or distance of the spurting fire. Anaximander thought the sun was twentyseven times the diameter of the earth distant from the earth’s surface, and the moon eighteen times. The sun’s hole was as large as the earth. There is no limit to the number of worlds both simultaneous and successive.

Life arises from the slime left by the evaporation of the water. Man in the beginning had a fishlike form, and was covered with a prickly bark. All animals indeed were clothed in bark, which later broke off. This seems to indicate that Anaximander had some conception of adaptation to environment.

Schopenhauer has a good deal to say about his idea of cosmical justice. Whatever comes into existence must pass out of existence. Existent things encroach on one another and must make requital for their “injustice” according to time. In other words, definite properties imply destruction; nothing perceptible can persist. The perceptual is that which has been separated out, a partial aspect of the, suffering an unaccountable lapse from true being. True being has no definite perceptible properties, for if so it would come into and pass out of existence. The is above all becoming, and thus it makes possible the permanence of change. It is that to which no limits can be applied, and thus it makes limits possible. The problem has really shifted to that of the One and the Many.*

Anaximander is like Thales in believing that the

is one and the source of change. But he is unlike in that he emphasizes the many rather than the one. His chief problem is not the nature of the prime matter, but the explanation of change and multiplicity. He is unlike too in holding that the source of things is unlimited, and that it has no perceptible quality. Thales could see and touch his water.

Notice the purely scientific, detached, impersonal tone of all this. It is an attempt to account for given facts without resorting to personification or traditional mythology. There is a certain splendor of thought, a range and power of style. It is impossible to think of him as a merely comical figure. His significance is less in his results than in his intention, yet his is a permanent scientific achievement, and he was a thinker of the first rank.**

Anaximenes was an associate and follower of Anaximander. He was born about 586 B.C. He also wrote a

in simple, unassuming prose. He accepts the theory of an unlimited living matter, which is the source of everything, having its motion in itself. But he identifies this matter with air, whose advantage over water is that it does not need to rest on anything. His statement is, “Just as our soul, being air, holds us together, so do breath and air encompass the whole world.” He uses here (Theophrastus says for the first time) the word

for which the Latin translation is “mundus.” This word may mean “adornment”, or it may mean “orderly arrangement.” For Anaximenes the world is an ordered system under the influence of a single force; all the parts are interconnected with each other and with the whole. Both Pythagoras and Plato develop this idea of a mathematical universe. The world is like the human organism. It breathes as our bodies breath; this breathing is not a function of the body nor of the world, but of the living air which pervades and encompasses and is the source of everything. This air is a divinity, the living motive force of all creatures.*

There is no sifting out of elements as for Anaximander. The air simply expands and contracts, and difference in quality is difference in volume. By expansion or rarefaction air Decomes fire; by contraction or condensation wind, cloud, water, earth, stone. (The proof is, when we breathe with our mouths open the air is warm; with mouths closed, it is cold.) The sun and moon are formations of vapor so thin that they burst into flame. The stars are thin air driven like nails into a glass-like shell of thickened air. The earth is a flat, table-like disk. The sun is broad like a leaf. They float in the air like covers held up by steam. Sun and moon move in circular revolution, but horizontally; at night the sun is behind the mountains. Notice that Anaximenes has somehow lost the idea of the ecliptic. Earth-quakes arise when great drought suddenly follows great rains. Here again we have a great naturalist.

STUDENT NOTES FROM WHITEHEADS’ LECTURES ON PLATO’S FORERUNNERS

II. The Beginnings of Philosophy

III. The Milesian School

IV. The Pythagoreans