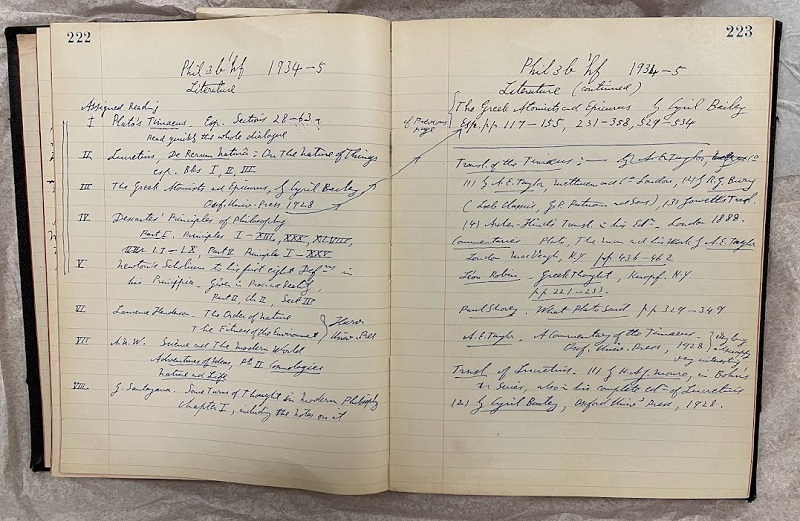

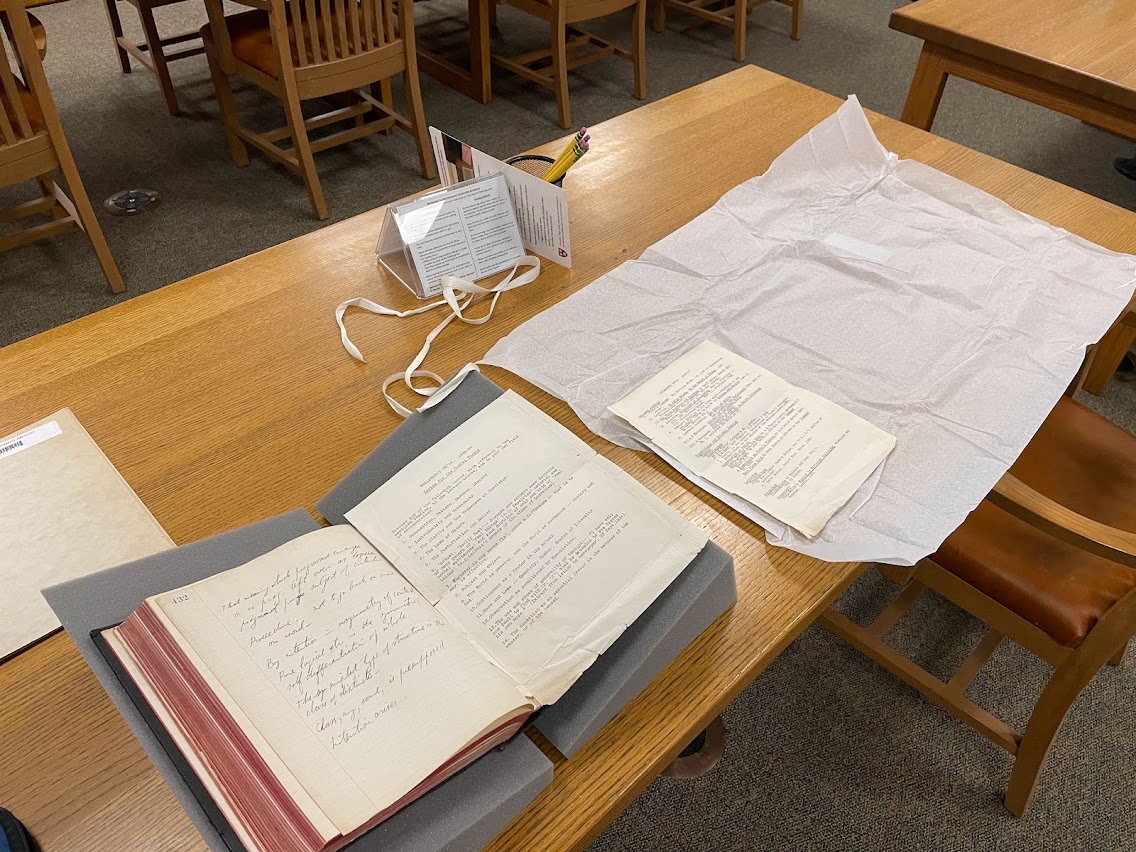

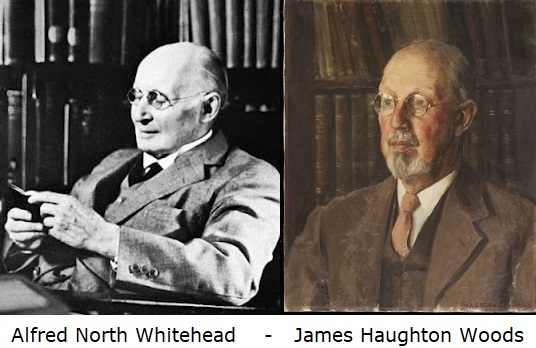

STUDENT NOTES FROM WHITEHEADS’ LECTURES ON PLATO’S FORERUNNERS

1934

complited by

Harvard Professor of the Philosophical Systems of India

II. The Beginnings of Philosophy

III. The Milesian School

IV. The Pythagoreans

- The Pythagoreans

Heracleitus continued the Milesian tradition with his doctrine of cosmical fire, which seems however in his description more like a sort of impersonal divinity than a physical unit. Xenophanes and Pythagoras, though strongly influenced by certain doctrines of the School, represent a break with it; they are the forerunners of the scientists of Southern Italy at Elea and Croton. Xenophanes was a theologian rather than a physicist. He criticized popular beliefs, and insisted on the unity of God, a monism so intense that experience is ignored. The Eleatic School, founded by Parmenides, accepted this unity, which is logical rather than hylozoistic, and taught that change is unreal. There is a fundamental difference in temperamental type between the Eleatics and the Milesians. Each seek more life; one group finds it in changelessness, the other in increasing complexity of change. Plato was a man of the rirst type, Aristotle of the second.

There is a long interval between the Pythagorean Order, founded by Pythagoras, and the Pythagorean School, with its mixture of science and religion. Pythagoras’ chief interest was different from that of the Milesians; not the unity of the world, but the destination of the soul was his concern. He reverts to the Dionysian point of view, seeking liberation from the aridity and paltriness of everyday existence. Influenced by Orphism, he announced himself as the revealer of a method designed to improve the lot of the soul in its successive re-incarnations and to deliver it finally from its unnatural and painful connection with the body. All this is in violent opposition to the Homeric scheme, and Pythagoras reports that on his descent into Hades he saw the soul of Homer hanging from a tree surrounded by serpents. The Pythagorean School later found salvation in the idea that there is proportion in everything (“all is number”), which remains constant througjh all changes and contingencies. Much of the best in Plato and in European science we owe to the Pythagorean School.

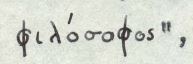

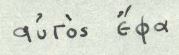

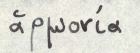

Pythagoras was born on the Island of Samos, an Ionian colony, about 570 B.C. Miletus is very near, and he was probably for a while a pupil of Anaximenes. There are distinct reverberations of the cosmic air in the Pythagorean number theory, and other traces of Milesian influence. Heracleitus speaks of Pythagoras’ thirst for knowledge; Herodotus calls him the best known of Greek thinkers. His extraordinary range of knowledge he acquired, not in any school, for there were none at that time, but through travel and conversation. When the tyrant of Phlius asked him his calling, he replied

”meaning ’’searcher for knowledge”; this was probably the first occurrence of the term. He represented life as a game, where some come for fame as victors, some for gain as merchants, some (the noblest) out of curiosity or interest as spectators. The spectators alone are capable of detachment and of penetration beneath the surface. So we, coming from another body and another world, need not become entangled in this one; the noblest attitude toward life is that of contemplation. This is the highest activity of the soul, and the best means of purification.

The cult of Bacchus, with its secret doctrines of the soul, its ecstatic trances and wild ritual dances, was powerful at the time, and Pythagoras was swept away by these fervid wanderers. But he was not satisfied with orgies and secret meetings. For the order he hoped to found, he sought the support of the tyrant of Samos, in vain. In 530 B.G. he left his native Ionia and migrated to Magna Graecia in Southern Italy. Here the inhabitants were of Dorian and Achaean stock, and the language and customs were strange to Pythagoras. The Dorians, in contrast to the lonians, were an uncultured, stubborn, fighting people. But they were good organizers, and once aroused by Pythagoras, they were like ’’moutons enrages” in their enthusiasm. Here, too, the ground was well prepared by Orphism; the upper classes were especially ready. The movement started by Pythagoras rapidly expanded, absorbed the city of Kroton, and ultimately developed into an aristocratic state or league extending over the South Italian cities as far up as Tarentum. This was like Calvin’s theocracy in Geneva or Puritanism in New England. All laws and political institutions were regarded as preparations for the world to come. Pythagoras was treated almost as a god, and had a temple where he gave out dicta from behind a veil. His

(ipse dixit) was the ultimate authority.

When such a society increases in size it decreases in quality. In 510 Kroton made war against Sybaris, which was destroyed. In dividing the lands quarrels arose. Pythagoras left Kroton and died at Metapontum about 500; in 440 there was a democratic revolt, and the order was dispersed. But like the Templars, the scattered members went about in Greece, spreading abroad the doctrines and making converts. There were revivals until the time of Cicero, who speaks of seeing the house where Pythagoras had lived in Metapontum. The order appeared in Athens a generation before Plato, about 450 B.C., and the ideas were much discussed. Burnet believes that Socrates was a member of the inner circle; that both Socrates and Plato were influenced there is no doubt.

The primitive society consisted of three hundred members. These men were interested in politics, and in attempts to promote social justice; and compassion was regarded as a means of freeing the soul from paltry ends. Another source of improvement was music; flutes and cymbals were considered dangerous, the lyre ennobling. (Plato took this very seriously.) Certain foods also were prohibited; and there was an elaborate system of taboos, symbols, mystic words and formulae, dramatic representations, bodily exercises. The surest means of purification was mathematical science, because of its disinterested character; and there was later a break between the ascetics and the scientists.

An applicant for admission was examined at length. His parentage was investigated, his own physiognomy and behavior appraised. This test period lasted for three years, and was followed by a novitiate of five years. At the end of this time the neophyte transferred all his worldly possessions to the order, and agreed to maintain long periods of silence, assimilating the doctrines without discussion. During all this time, the voice of Pythagoras had been heard, but his person had been concealed. When the novice was finally admitted to behold the master’s face, he became an esoteric (rather than an exoteric) member of the order, and was allowed to take part in the affairs of the city.

Communal life only lasted throughout the day; in the evening the members returned to their homes, and the family recovered its rights. The day began with a solitary walk, the members then assembled for study, instruction in manners, and gymnastic exercises. After lunch there was discussion of political problems till dusk, then the studies of the morning were reviewed in groups of two or three. The members then bathed, ate a ceremonial meal together, preceded by libations and sacrifices, listened to a reading by the youngest disciple and an enunciation of precepts by the oldest, and separated.

The members were divided into groups, each with a specialized task. The mathematikoi were the scientists; they had charge of the education of the neophytes. The sebastikoi (called by the Romans “beati docti”) contemplated the order of the universe with veneration, practised unifying meditations, and were considered to be perfected mathematikoi; we should call them aestheticians. The diakonoi* looked after the social side; they had the task of increasing cooperation in the city, so that the music of the muses might permeate it, and the harmony of the universe be increased.

*One set of student’s notes has “politikoi.

The senatores were entrusted with the patriotic duty of seeing that the harmony wrought out by the ancestors was transmitted to the younger generation. The applicants were called akoustikoi, and the graduates physikoi; the latter were those whose righteousness, science, etc. had become automatic.

The central problem tor the Pythagoreans was the purification of the soul; and the instrument of purification was conceived to be “justice”, based on the idea of transmigration. Their theory of metempsychosis was founded on that of the Egyptians, and Plato later took it over.

To primitive man the continuousness of life is more apparent than its brevity. Death he regards as a mere temporary embarrassment, and all he asks is that the animal satisfactions of this life should be prolonged and increased in some ideal state, or “happy hunting-grounds.” The belief in mere continuance is not religious; religion and morality begin when the idea of value arises. This is naturally expressed in the notion that the future life contains recompense and retribution for deeds done here. The combination of the two ideas, continuance and compensation, is the basis for theories of metempsychosis. These are of several types.

Our knowledge of the Egyptian theory is incomplete. On the monuments there is almost nothing. The Book of the Dead* deals with something which is not quite transmigration, but rather the magic process of assuming a new personality (hawk, phoenix, heron, swallow), and of union with the god**. On the other hand, there are accounts in the cursive records reaching back to 500 B.C. Probably Herodotus had access to these later hieratic texts, the ideas of which very likely came from Persia, or in the beginning from India.

*Chapters 86, 87, 88. See also the Alexandrian Fathers, and Herodotus, ii, 123.

**Primitive man worships animals superior in strength or craft. There is no difference in genus between man and animal, and the idea of metamorphosis is thus a natural one.

The soul was conceived to be imprisoned in an animal body, because of transgressions in a previous life; the form of this body corresponded to past desires. There was a fixed cycle of rebirths; at the end the soul appeared before Osiris, who determined whether it was ready for release, or whether it must go the rounds again. In the former case Osiris, who had himself been the first man to find his way to the sun-god, conducted the soul to the West, where it was re-absorbed in the sun. Pythagoras organized and transfigured these beliefs, and represented them in the mysteries by symbols. We are fallen gods, and this divine estate is regained when we are freed from the custody of the body. Meanwhile we are bound to the wheel of birth, and in successive lives go on acquiring the matter which fits our desires. There are periodic judgments, and for those who have achieved purification there is release. Notice that continuance is now regarded as a sort of doom or penalty, whereas it was originally looked forward to as a “happy hunting-ground.” There has been a revolt against the idea of living forever.

Pythagoras thought of the man as a tenant of his body; from time to time he moves. Buddhism, which believes in no fixed cycle, no assurance of final escape, found this thought intolerable. So the soul is broken up, pulverized into atoms, until there is no individual left to transmigrate. For Buddhism there is no soul substance. I am a continent of overlapping mental atoms temporarily together; this complex depends on past desires, as in the Pythagorean theory – I am just what I have wished to be. Strictly there is no transmigration, but rather a transmission of tendencies to action, which collect for themselves appropriate instruments, or bodies. I am a verb, not a noun or a substance. The idea of continuance remains, but what continues is not the soul, but a predisposition to action.

The law that each wish carries with it inevitably its own fulfillment is Karma. Desire in itself is not evil, only desire for the wrong objects. Self-centered craving is the cause of pain. If you try to accumulate for yourself such things as plumbing and food and mundane satisfactions you become the slave of those things. The escape is recognition of the oneness of all life. Then each desire will be thrown for appraisal against the whole field as a background, all will fall into proper proportion, and only desires which unite one to the general life will have power. Nirvana is the going out of selfish desire, not the going out of the soul, for there is no soul to go out. As the desires become weaker, their discharge in the next life also weakens, and finally corporeal existence is overcome. This occurs at no fixed point in the cycle, as in the Egyptian system, and there is no judgment; the process takes place automatically according to the law of cause and effect as Buddhism conceives it.

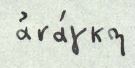

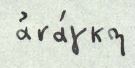

Theories of transmigration face in two directions. They try to answer not only the question, “What will become of me after I die?” but also “How explain the present injustice?” The real problem is that of morality confronted by brute force. The Greeks called this force

which is usually translated “fate” or “necessity.” That won’t do

was an uncontrolled, arbitrary, and

irresistible power – the tragedies show what havoc it could wreak on a family. The Moslem idea is a glad submission and acceptance, a worship of force; Allah requites as he will, and all you say is ’’Allah is good.” In Buddhism, Pythagoreanism, and later in Plato, the answer to the question “Why does the good man suffer?” is “Because he desired the wrong sort of things in a previous life.” Thus he has no right to resentment.

Transmigration theories are also important in relation to ideas of change and permanence. They attempt to get out of the realm of primitive satisfactions and emotions into the realm of science and of value. Plato was interested in permanence and distressed at the instability of things; he thought change could be explained by certain permanences. The result of the fickleness of the soul is chaos unless you can connect with something which does not change, something which, like the number rive, remains identical regardless of the multiplicity of its recurrences.

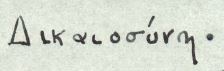

The Pythagorean novice, at the start of his preliminary period, was sent to a temple of the muses to dedicate himself to harmony. The muses were a choir whose music was indissoluble, permeating the universe, creating cosmic order. Originally order appeared mythologically, in charge of the goddess Dike, daughter of Zeus. And similarly truth, the goddess Aletheia, was at first the personal property of Achilles, sign of his power and pride. (Among the lower populations of the East today there is a similar idea – the truth is whatever you want to hear.) Then these personified forces become abstract and tend to combine. Truth and order become public properties, binding on others as well as on yourself. The Sophists thought of laws as mere human customs to which you conform, having nothing to do with truth.* But Plato won’t admit this: no human custom is of any value apart from the truth, and the truth is something that does not change. Numbers, music, astronomy, are aspects of this radical order, or “unwritten law”, which makes the cosmos. The term for it is

“Justice”, Jowett calls it in the Republic, but this is not quite right. It is a general term tor law or order, the proportional distribution of things.

For the Pythagoreans justice was three-fold; and the parts are distinct though they over-lap, Themis is the law which governs gods, kings and heroes; Nomos is law on the human level; Dike is the law for the dead. Themis prevailed in the relations between gods and men, as an equity correcting false judgments; Pythagoras said there was a Themis even for animals. It could never penetrate into Hades. Dike, on the other hand, might apply in the world, but never in Heaven.

In the Antigone, and also in other tragedies, Nomos and Dike are in conflict.

According to this view, all being is justice (Cf. Anaximander’s theory that change is injustice.) The whole universe is governed by one law, and everything has its place in the well-knit whole. (Plato insists on this interplay.) The cosmos is not something that is manufactured out of a lot of discrete parts, nor is it a product of chance. And the city, like the universe, is a living organism, based on permanent standards and norms which are its character or

Thus to make a constitution would have been absurd. The ileal city is of course an aristocracy. But how to find the right ruler? So this ideal had to be modified to allow certain types to possess power. Thus you have the predominance of a scientific, aesthetic, ethical society which happened to be ascetic as well.

The magistrates do not make the laws. They receive them from the abysses of the world, as a mandate to be transmitted to posterity. Nor do the rulers rule arbitrarily. Their task is to see that the cosmical law is equally accessible to all the people. The greatest evil is anarchy. If reverence for the law is lost, its opposites are released – senuality

and excess

leading

destruction ![]()

The passions are to be distrusted (the Sophists tried to arouse them) because they blind us; man’s essence is the discernment of relative values, and if this is lost he fades away. The soul is akin to the gods; the function of the judge is to help it regain its lost estate. He is the healer of the soul, not the mere imposer of penalties, whom Plato in the Laws (IV, 720) compares to a quack doctor.

The life of the city is the concord of different elements in a proportional equality. The general principle is equal rights for all, including the dead.* But this is not, like Homer’s,** an arithmetical equality, based on the idea that one man is as good as another. What is equal for all would not be right for each, nor what is right for each necessarily so for all. The distribution of rights is in accord with the essential differences of the citizens, who vary in cosmic importance and value. The symbol for this geometrical equality is the square, the product of equal factors, which is infinitely variable in size and position while its form remains constant. Plato’s justice is this proportional equality, which harmonizes discordant elements and gives everyone his own place in the universe. Such justice does not merely apply a rule, Out treats each case as unique, distributing equity in accord with value. The work of Zeus is to geometrize, by his judgments giving structure to the universe.***

*Indeed the dead had more rights than the living (Cf. Sophocles).

**”Each laid his hand upon the equal feast.”

***See Laws, 757. Of. Protagoras 320 (The Myth).

The laws of a city correspond to the laws of music: law is to soul and life as harmony is to voice and hearing. We must try to understand the view the Greeks had of the primary importance of music.* The study of music was regarded as fitting preparation both for politics and philosophy; it was not to them a mere pleasure of the senses, but a revelation of ultimate being. Through insight into its structure we escape from the barriers of the sense** world, and gain insight into the

that constitutes the world-soul or cosmos. Our rhythms correspond with the world-rhythms, and the fate of a man depends on the kind of music he can understand. Aristotle, Democritus, and Plato all accept this point of view. It is symbolized in the myth of Orpheus, who was able to charm the animals through their participation in the harmony which is the source of all life.

*Apparently J. H. W.’s discussion of Greek music depended on some theories of Professor E. Franck.

The dithyramb in praise of Dionysus included words, music, and dancing, all based on a common pattern. There was no polyphony, no harmony, no instruments; melody and rhythm were highly developed. The words were chanted in a solemn, monotonous utterance akin to the Gregorian. In the fifth century (c. 440) there was a change. Agathon introduced what Plato calls the ’’new music”, and criticizes as being sensuous and personal rather than cosmical.*

A soloist singing against the accompaniment of the chorus took the place of the chorus singing alone, chromatics began to appear, simplicity was lost, and the fine, impersonal, formal character gave way to the expression of individual emotions. The old music was a contemplation of the law, the new only a thing to be enjoyed. There was a similar change in drama, in a new emphasis on individual characters (Euripides), in religion, and in sculpture, where Praxltelean seductiveness reigned, the representation of the typical man began to give way to the portrait, the more erotic and personal Aphroditae to appear.

The mathematikoi had discussed the nature of rhythm, but music did not become a science until Archytas of Tarentum. We have the mathematical and some of the logical and ethical fragments of Archytas. Aristotle wrote of him? the Stoics venerated him and ascribed many of their theories to him. He created the science of acoustics and the earliest form of mathematical physics. He distinguished arithmetic from geometric proportion, and applied this to music. He was interested in the metaphysical basis, and in the connection between the soul, the structure of the music, and the cosmic harmony. Heard music he believed to be a faint echo of the cosmic music.

*Plato objects to the use of the lyre and flute, to the sensuous imitation of individual sounds, the attempt to externalize the form of things. Cf. Laws 669D . Phaedo 601D. Republic 396 B.

Democritus had a similar theory. He thought the four fundamental sciences were arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music; these represented different types of harmony in the soul. But Democritus despised reliance on sense-data, and didn’t test his hypotheses by experiment. Archytas, on the other hand, demonstrated his theories by what Aristotle calls ’’the facts.” He made an exact mathematical calculation of tonal relations in terms of lengths of strings. This is the first time we have complex physical relations expressed accurately in quantitative terms. The discovery that the structure which corresponds to our emotions is mathematical suggested that the emotions might be so likewise. This leads to a quantitative view of the universe, in which colors and other sense qualities, as well as sounds, are mere appearances of an underlying quantitative reality. The is no longer thought of as a substance, thicker or thinner, but simply as number.

J. H. W. discussed this quantitative view later in connection with Plato’s “ideal numbers” and the Idea of the Good. There is also a comparison with Democritus and Anaxagoras.

*Cf. Schelling, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Wagner., Schelling; said his view was iuentical with that of the Pythagoreans.

**Of. The mediaeval quadrivium.

STUDENT NOTES FROM WHITEHEADS’ LECTURES ON PLATO’S FORERUNNERS

II. The Beginnings of Philosophy

III. The Milesian School

IV. The Pythagoreans