The View from Delphi

Rhapsodies on Hellenic Wisdom &

An Ecstatic Appreciation of Western History

Orpheus, The Katha Upanishad, and the Secret Way Beyond Death

Pure Friends!

Sons and daughters of the earth and starry sky!

Escape from the Spindle of Necessity and

the sorrowful, weary round upon the Wheel of Birth.

Enter the wreath of heaven

from mortals become gods

Look up from the Pool of Lethe

to the White Poplar Tree.

Listen to the counsel of Rhadamanthus

the Judge of the Dead

to the Refreshing Waters of Remembrance.

Religiously Practice Remembrance.

Coming from the Pure

Drink there the sweet ambrosia

Quenching every thirst

by the grace of the releasing divinities.

Rise with winged enjoyment

to the privileged Fields of Elysium

Where Blessed Company awaits.

O happy and blessed one,

thou shalt be god instead of mortal.

Initiates! Follow the divine!

Discipline the prison body! Balance! Purify!

Abstain from eating anything that breathes

like you do.

Live a purifying and temperate life

devoted to the Unlimited.

Follow the god

and move from closed to Open Eyes.

Awaken to the Island of the Blest!

Behold the flowers of gold blazing,

and on the shore, radiant trees,

or drink again in the waters of Rememberance

In Good Company, practice Rememberance.

With intertwining rising hands

crowning the ecstasy

Open Eyes

Like a kid who has fallen into milk

Divine Distraction

Enthusiastic Prophets

with the Divine Vision

Open only to the soul in God

inspired, filled with God.

— sample collection of Orphic saws

Orpheus or Orphism is mentioned directly or implicitly in almost every major drama, philosophical treatise or theological rhapsody of the ancient Hellenes. The teachings ascribed to “Orpheus” were so thoroughly widespread in the ancient Hellenic world — especially in the formative pre-Socratic era — that Orphism could be said to be the spiritual background of the Hellenic miracle. But if asked to give a summary of “Orphism,” most would be taxed — all but the classicists, and even their answer would be “academic” in its portrayal. Yet, if we look carefully, that is, with a heightened spiritual sense, we can see that the tenets and teachings of Orphism merged into the very fabric of the Western mind — and by such interwoven familiarity has become essentially forgotten. It behooves us to transcend our blindness of familiarity and look with fresh eyes upon Orphism, not as a scholarly investigation and speculation– that has been done, but to behold a complex religion of wondrous force.

Orpheus or Orphism is mentioned directly or implicitly in almost every major drama, philosophical treatise or theological rhapsody of the ancient Hellenes. The teachings ascribed to “Orpheus” were so thoroughly widespread in the ancient Hellenic world — especially in the formative pre-Socratic era — that Orphism could be said to be the spiritual background of the Hellenic miracle. But if asked to give a summary of “Orphism,” most would be taxed — all but the classicists, and even their answer would be “academic” in its portrayal. Yet, if we look carefully, that is, with a heightened spiritual sense, we can see that the tenets and teachings of Orphism merged into the very fabric of the Western mind — and by such interwoven familiarity has become essentially forgotten. It behooves us to transcend our blindness of familiarity and look with fresh eyes upon Orphism, not as a scholarly investigation and speculation– that has been done, but to behold a complex religion of wondrous force.

We need only to look at Plato to see the pervasive effect of “Orpheus” upon Western civilization. And if Western philosophy is the footnotes of Plato (as proposed by the twentieth-century philosopher, Alfred North Whitehead), it could also be said that the pre-Socratics are the bibliography. The literature and legends of Orpheus, the Orphika, is then the inspirational source text. In fact, Plato, and many after him, could quote line for line from the legendary Orphika — usually on matters of the immortality of the “soul”. Speaking as a Westerner, our conception of our very souls is Platonic, and therefore imbued with “Orpheus.”

In the Phaedo, Plato honors Orphism in the very highest regards and twice equates the soul of “true philosopher” with that of the realisers of the Orphic mysteries. “For the initiated are in my opinion none other than those who have been true philosophers.” On his last day alive (according to Plato), Socrates did not speak of politics or Forms above forms, or even the kinds of love, but appropriately was full of “the ancient teachings” about the Underworld Orphic tour that the soul navigates after death.

Fortunately, we have an abundance of fragments about “Orpheus” and Orphism. Unfortunately, they are scattered along a millennia, from before and after recorded history and numbered time. In fact, the fragments are so scattered, old, and suspect, we cannot even “prove” that Orpheus himself ever existed. Indeed, the “evidence” is twofold that he was and wasn’t an actual historical person.

In fact, it has been debated for millennia whether Orpheus an historical person, a figure of legend, or a collection of stories. Certainly, he could be all of those things. Apollodorus bluntly states that Orpheus “invented the mysteries of Dionysus.” On the other hand, many (including Aristotle, over three hundred years after the time of “the Master”) claimed that Orpheus was a mythic creation from the “Rhapsodies” of Onomakritos — the court seer and revered “Orphic Initiator” for the ruler of Athens, Peisistratos. Others have attributed the twenty-four sheets of pure gold (the lamellae) inscribed with Orphic scripture to Pythagoras. The debate on Orpheus has gone on for twenty-four centuries and his corporeality has never been a scholarly certainty.

While scholarly propositions on the reality of Orpheus often look for historical evidence and then reports on found facts, the debate fails to account for the deeply-moving meanings of the found material itself. Therefore, instead of again surveying the body of Orphic literature, or touring the landscape of scholarly opinion, let us focus on the teaching itself, the sacred words, and therein consider if we find simply stories, myth, and a primitive religion — or a deeper, penetrating, and moving understanding. Indeed, it is my contention that finding such penetrating revelation would be the clearest evidence that Orpheus was in truth a real person — for only a “prophet’s words” could inspire the Hellenes with such transformative force.

Therefore, let us proceed as theological, forensic scientists and reconstruct the complexion and face of Orphism from the metaphorical skeleton, and, as we shall see, the “singing head” of Orphism that we do possess.

Probably the most thorough work on Orpheus was done by W.K.C. Guthrie, who came down squarely on the side that assumes at least one great mystic took on the legendary name of “Orpheus.” But as he points out, the naysayers make good points as well, and the misty, pre-historical time is no place to argue facts. Contradictions exist: for instance, “Orpheus” predates Homer as he is mentioned in the Iliad (~725 BCE), yet Orpheus’ theological teaching would have to post-date Hesiod ~710 BCE (as we shall see later). Paradoxically, to bridge the gaps in the “evidence,” Orpheus needs to be both an historical person with a legend and a demi-god with a myth.

After Hellas reassembled an alphabet and reachieved literacy — as evidenced by Homer and Hesiod — she began a period of what has been called the “orientalization of Hellas”. Babylonian Zorastrianism as well as Brahmanic Upanishads can be seen infusing Hellas with their finest words.

Herodotus reported that in this early literate period, Orpheus “hailed from Thrace, the greatest nation on earth, outside of India.”5 Thrace was well-known for its cosmopolitan position at the far western end of the great caravan roads that led east to India, where wise men were exposed to the Upanishads (800&endash;400 B.C.E.). While records cannot be substantiated with weak facts, it is not difficult to see how some Thracian “prophet” or god-possessed priest took on the mystic name “Orpheus” as he enjoyed the spiritual teachings from “the spiral origin, the seat of the world,”6 Upanishadic India.

Herodotus reported that in this early literate period, Orpheus “hailed from Thrace, the greatest nation on earth, outside of India.”5 Thrace was well-known for its cosmopolitan position at the far western end of the great caravan roads that led east to India, where wise men were exposed to the Upanishads (800&endash;400 B.C.E.). While records cannot be substantiated with weak facts, it is not difficult to see how some Thracian “prophet” or god-possessed priest took on the mystic name “Orpheus” as he enjoyed the spiritual teachings from “the spiral origin, the seat of the world,”6 Upanishadic India.

In fact, the similarities and transparencies of the Katha Upanishad and the contemporary teachings of Orpheus are striking: both were grounded in conversations with the Lord of Death; both speak of austerities and acetic purification (katharsis); both harp upon the immortal soul beyond birth and death; both speak of discriminating between semblance, binding illusion, and liberating Truth. Both the Upanishads and Orphism call the listener to renounce the false and choose the Real, and by this conversion, both speak of inheriting “eternal,” “perfect ecstasy.”

It is no affectation that the Orphics referred to one another as “Katharoi,” usually translated as “Pure.” More meaning can be harvested as we note that “Katharoi” alluded to the purifying katharsis that was the necessary foundation to a divine life; the kathartic message is clear: spiritual work was first a purifying preparation. Kata or “down” is the root of katharsis, indicating one has gone down and returned, purified. And “Katha” is the name of the sage who wrote the Katha Upanishad and founded the Kathaka school belonging to the Yajur-Veda. His name, like the word katharsis, has etymological roots which translate as “purification.” To study “Pure Orpheus” and Orphism, we must review the Katha Upanishad, study what Orpheus studied.

Yama, the Lord of Death: “The Hereafter never reveals itself to a person devoid of discrimination, heedless, and perplexed by the delusion of wealth. ‘This world alone exists,’ he thinks, ‘and there is no other.’ Again and again he comes under my sway.” — Katha Upanishad I.ii.6

Prior to the Upanishads, mythology and shamanism was the extent of religious knowledge and experience. As the myth-laden Vedas evolved into the discriminative Upanishads, the shamanistic, body-based urge for free-feeling was finally satisfied and completed in the rare air of mystic realization: the ambrosial, unchanging consciousness that witnesses all changes, all transformations, all states– waking, dreaming, sleeping, and dying. That mystic and sage understanding was introduced into the West with Orphism.

Up until the Upanishadic Orpheus, the shamanistic rites of the West were best known through the intoxicated ravings of Dionysus. These celebrations served to resurrect, enliven, and illumine the spirit of the celebraters, the bacchants. With the advent of “Lord Orpheus,” mystic consciousness enlightened those mysteries with Apollonian penetration and harmony. Apollo was said to have come to the Hellenes through Thrace from Vedic Hyperborea.

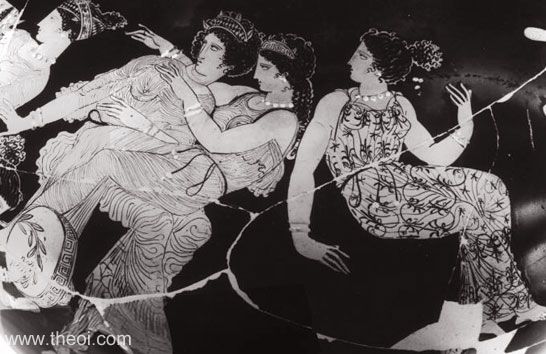

Just after literacy congealed the bardic legends, the “oriental” Dionysian religious practice of intense celebration, orgia, spread like wildfire across the Balkan peninsula.8 For the ancient Hellenes, the orgiastic teachings and shamanistic rites promised a spiritual release through raving celebration, or bacchos ecstasy. These Dionysian celebrations served to resurrect, enliven, and illumine the spirit of the bacchants, the “ravers”. For the participants, the Dionysian celebratory rites served to transform all that was subjectively dark into ecstasy– or, to borrow a phrase from Blake, Dionysus indicated “the path of excess that led to the palace of wisdom.”

Just after literacy congealed the bardic legends, the “oriental” Dionysian religious practice of intense celebration, orgia, spread like wildfire across the Balkan peninsula.8 For the ancient Hellenes, the orgiastic teachings and shamanistic rites promised a spiritual release through raving celebration, or bacchos ecstasy. These Dionysian celebrations served to resurrect, enliven, and illumine the spirit of the bacchants, the “ravers”. For the participants, the Dionysian celebratory rites served to transform all that was subjectively dark into ecstasy– or, to borrow a phrase from Blake, Dionysus indicated “the path of excess that led to the palace of wisdom.”

However, in response to the excesses of Dionysus, another voice emerged in the seventh century, the Apollonian song of Orpheus. Both Orpheus and Apollo were said to have come to the Hellenes through Thrace from Vedic Hyperborea, about the time of the Upanishads. With the advent of “Lord Orpheus,” mystic consciousness enlightened those shamanistic mysteries with Apollonian penetration and harmony. This transformation was universally acknowledged throughout the ancient world, so that by the sixth century, the poet Ibykos referred to the Master of the mysteries as “famous Orpheus”.

Orpheus was “the realizer of Dionysus” and “Priest of Apollo,” triumphantly acknowledged as the one who tamed, measured, and revealed the meaning of the intoxicating rites. He was called “Lord (or) Master of the Mysteries” for over a thousand years, and was also known as “the Prophet who enlightened the raving rites.”

“Clothed in radiance,” the legendary Lord Orpheus brought Apollonian stillness, temperance, and restraint to the sensual shamanic. As the Western hymnist of Upanishadic realization, Orpheus represented the mystic completion and transcendence of shamanism in ancient Hellas. Restrained, yet unsuppressed, free within the limits of harmony, Orphism balanced pleasure and wisdom, body and soul, outgoing and inward energies, joy and transcendence.

“When the five instruments of knowledge stand still, together with the mind, and when the intellect does not move, that is called the Supreme State. This, the firm control of the senses, is what is called yoga.” — Katha Upanishad II.ii.10

The avenue for this enlargement of conscious joy began for the Orphic practitioner as a cleansing, followed by a deeply expressed communion, which in turn matured into an ecstatic self-realization.13 This three-staged way of purification, sacred communion, and ecstasy expressed itself in invocations, in rhapsodic, sacred hymns and wise teachings, in the noble call to limit-transcendence, and, it was said, by the mysteries and divine presence of the source person: “Reformer and Prophet” Orpheus — and through the lineage of his initiates. As Walter Wili so clearly stated (1944), “The Mysteries are then the common line between the Paleolithic shaman and the tragedian of the classic age.”

Purification and Remembrance

Unabashedly Western, the Orphics used the natural harmony found in pleasure as the first sign of the transcendental harmony. Dionysian sensual dance and intoxicants, the music of the flute, lyre, drums, and the incantations, recitations, and poetry of the theologoi (the men attending to theos logos, the logic of the divine) all combined to guide the feeling, breathing psyche toward the joy that is unlimited. In joyous ecstasy, the immortal nature of the soul flashed forward and the initiate began the great transformation to a life divine. Ecstasy was considered the evidence that flesh may intercourse with the divine, proof that the union with the immortal was possible.

The substance of the Orphic life was to prepare the soul for sustained ecstasy, to live a life signed not by the usual destiny of ordinary self-fulfilling pathos but by balanced, self-transcending divinity (apathos). This katharsis had many implications in behavior and prescription; the most mentioned was vegetarianism and general nonviolence. “He taught men to abstain from killing.” Many of these Orphic precepts prescribed the spiritual necessity of engaging the balanced, moral life as the cleansing foundation of sustained religious embrace.

This balancing life consisted of vowing to a life of moral actions, dietary restraints, study, meditation, and purifications (such as fasting). It is interesting to note that Orphics ritually daubed their skin with wet clay and let it dry to absorb impurities. Another earthly (and meditative) ritual is seen in the Orphic practice of being buried up to the neck in the mother earth — serving not only the purification of the body, but also requiring strength in “utter stillness,” hesychia.

Thereupon balanced, cleansed, and stilled by the way of Orpheus, every intoxicating ritual of Dionysus was an occasion to release feeling and realize the divinity of existence. It was noted that only those who were well-cleansed could behold the vision of sustained ecstasy. For those dedicated disciples, the mysteries of divine communion (koinonia) and divine knowledge (gnosis) grew as an immortal and moral soul. Immortality came to those imprisoned as passing breathers*. [*psychein, “to breathe”, is the root of “psyche”]

The immortal psyche that became evident in growing balance and purity resonated to the ambrosial awareness found as the self-radiant, numinous essence of everything. The harmonia of the kosmos overwhelmed the inner being and the soul found itself already within the white divine.

For centuries in the ancient world, the phrase “according to him” referred to Orpheus, and, “according to him,” when one becomes cleansed by the purification work and divinity invades the body, the seat of right thinking is found in the diaphragm and full breath. Therein, the soul finds itself already rising and eternally resting in the royal Fields of Elysium. This enlightened joy began (in words ascribed to Orpheus) “the years of pleasure.”

The Transforming Soul of Orpheus

Even though Orpheus was legendary for his vibrant conduction of mystical divine power to those in his presence, this loving, direct experiential effect he had on people is often overlooked or dismissed. Speech about sacred company is easily misunderstood — especially in the West. This is partly due to the ineffable nature of all such experiences (which are therefore described in “mythological” metaphors), and partly due to the fact that the very notion of sacred transmission is unknown to most Westerners, incongruent with our world view of insistent independence — and therefore spiritual transmission is generally rejected, neither believed nor understood.

In the case of Orpheus, it was said that his lyre’s heart-force exceeded all animal and siren calls — and was reported to have even calmed the waters of a troubled sea. Like the Buddha touching the earth and transforming this world into the divine domain, Orpheus transmitted a lyric joy stronger than death itself.

Having realized Atman, which is soundless, intangible, formless, undecaying, and likewise tasteless, eternal, and odorless, having realized That which is without beginning and end, beyond the Great, and unchanging — one is freed from the jaws of death. — Ka Up I.iii.15

Prior to Orpheus, athanatos (immortality), was the epithet of gods and goddesses. Pure Orpheus was credited by his Hellenic descendants with the numinous drawing-down of the immortal godhead to the soul of man. By the wisdom and lineage of the “god-infilled Initiator,” the immortal soul became the essential mark of being human.

The wise man should merge his speech in his mind, and his mind in his intellect. He should merge his intellect in the Cosmic Mind, and the Cosmic Mind in the Tranquil Self. — Ka Up I. iii. 3

Orpheus was the first in the West to advocate a full-time devotion to the divine — not merely the social religion of cultural adherence, but a lifetime occupation. For the first time in the West, renunciation was possible as a religious path.

The golden sheets (the lamella) give us the triumphant voice of an Orphic adept in tones suggestively Upanishadic:

I have escaped from the sorrowful, weary round;

I have entered the ring desired with eager feet;

I have passed to the bosom of the goddess of the Underworld.

Happy and Blessed

My soul is immortal.

In the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, the followers of Orpheus toured Hellas, teaching those who would enter into the disciplines of Orpheus. For the first time in the West, devotion to the divine life became a full-time possibility. The priests of Orpheus had no holy ground or set temple, but they toured the land with scripture, meeting people in their own villas or humble huts, and they admonished their listeners to live an acetic life devoted to the divine.23 They carried the promise that those who fulfilled the disciplines would enjoy the same ambrosial Remembrance of immortal ecstasy.

The Orpheteletai, or Initiating Priests of Orpheus, intoxicated those who responded to their galvanizing with their ecstasy and knowledge. Exposure to the ecstasy of the priest brought telete, or “initiation.” Pausanias describes this initiator power thus: “Now in my opinion Orpheus was one who surpassed those who went before him in the composition of verses, and readed a position of great power owing to the belief that he had discovered how to initiate one into communion with the gods, how to purify them from sin, to cure diseases and to avert divine vengeance.”

This ecstasy was transmitted through their devotion and divine realization, demonstrated by ecstatic music, lyrics, and literature — and ritually augmented by the intoxicants of Dionysus.

Interestingly, telete is rooted in telos, meaning completion. Yet telete is translated into Latin as initiare! To be initiated is to feel the completion! The Way begins with divine intimacy. To receive initiation (telete) was to feel the transmission of divine communion from the god-possessed Initiator. It was to see, feel, and remember the “constant ecstasy” of the Master. The Orphetelete radiated their ecstasy through lyric ceremony, devotional hymns, and sacred rites — bodily, emotionally, and intellectually communicating the joyous ground for remembrance (anamnemisis).

Orpheus reminded his listeners in flowing sutras, “song stitches,” or Rhap-sodies; these rhapsodies served to purify the devotee of the Underworld’s persuasions of fleshy logic and lazy indulgences so that joyous anamnemisis, the spiritual practice of remembrance became one’s responsibility. When this remembering and regathering religious practice became stable in sustained embrace, the psyche was illuminated by the kosmic harmonia and theos came to the soul. This entheos or “god infusion” enthusiastically established a rich ground for sweet remembrance.

What was remembered? The Bright Source at the Core of Everything, Zeus (Indo-European root: dhyas, Bright): the singular, self-existing, giving light of Phanes, the Clear Light of Reality, Bright-Zeus. “Out of the One the many, and out of the many, the One,” goes the Orphic recitation. The Bright divinity, Zeus, was not a pre-rational, sentimental or mythic embrace for the sophisticated Hellene mystic, but was rational and trans-rational intuition realized to be at the core of everything, the source of all, the blossoming radiance and singularity of harmonia. In the words of Herakleitos, “The Wise is One Only. It is willing and unwilling to be called by the name ‘Zeus.'”

Or, again, in the words of the ancient Orphics chanting Apollo’s hymn,

ZEUS EVERYWHERE — ZEUS EVERYWHERE — ZEUS EVERYWHERE

Zeus the first, Zeus of the flashing lightning bolt the last; Zeus the head, Zeus the middle, from Zeus have all things been made. Zeus is the foundation of the earth and of the starry heaven; Zeus was male, Zeus was the immortal bride; Zeus the breath of all things, Zeus the rush of the flame unwearied; Zeus the source of the sea, Zeus the sun and moon; Zeus the king, Zeus of the flashing lightning, the beginning of all things. For he concealed all and again brought them forth from his sacred heart to the glad light, working wondrous things.

ZEUS EVERYWHERE — ZEUS EVERYWHERE — ZEUS EVERYWHERE

Prior to Orpheus, athanatos (immortality), was the epithet of gods and goddesses and a few heroes, like Heracles.29 Pure Orpheus was credited by his Hellenic descendants with the numinous drawing-down of the immortal godhead to the soul of man. This epochal change was noted with ancient clarity by the famed classics professor William Greene in his 1948 work Moira, “[T]he conception of the soul as divine, and the idea that it comes into its rights only in sleep or after death, are Orphic, and meet us here for the first time.” By the wisdom and lineage of the “god-infilled Initiator,” the immortal soul descended from the gods to the essence of being human.

Harmonia and Dike

Faced with an immortal condition, the soul embraced a new commitment to morality. Upon the strength of a balanced life, followers of Orpheus’ ascetic demands grew in sensitivity to the vibrance of divine joy — the joy that is distinct from body-based pleasures. They were transformed by this divine power into a new maturation and resonance — harmonia, defined in Orphism as “being in tune”. When the personal practice of harmonia became sufficiently strong, then one resonated to the harmonia of the kosmos. This wisdom was called sophia; this temperance, sophrosyne.

The theologoi spoke for the logic of divine existence (theos logos, theology), instead of the logic of body and belief. This theological preference for the soul’s importance over the fleshy orientation was expressed repeatedly as soma-sema, usually translated as “the body is a tomb.” It was through this chant (soma-sema-soma-sema) that Orpheus harped upon the immortality of the soul. Emphasizing the beyond-mere-body fountain of divinities, Orpheus emphasized attention to the soul’s needs by disciplining the body.

But the root meaning of sema is “a sign,” or “marks the spot,” and by this significance became associated with “tomb.” While the common understanding of soma-sema is “the body is a tomb,” a further implication of “soma-sema” indicated a sensitivity to how one was presently buried in his or her own mechanical existence, or spindle destiny. Understanding this already-underground, ordinary suffering was indeed the first noble truth of both East and West. Plato again summarizes, “Now some say that the body (soma) is the sema of the soul, as if it were buried in its present existence; and also because through it the soul makes signs it is rightly named sema.”

Beyond the senses are the objects; beyond the objects is the mind; beyond the mind, the intellect; beyond the intellect, the Great Atman; beyond the Great Atman, the Unmanifest; beyond the Unmanifest, the Purusha, the Divine Person. Beyond the Purusha there is nothing: the Divine Person is the end, the Supreme Goal. — Ka Up I.iii.10-11

The feeling, breathing psyche of Hellas was called atman in Vedic India, and both are translated into English as soul. It was this emphasis of soul over mere body and mere sentiment that formed the soulful way to immortal happiness — both in the Upanishadic East and the Orphic West. (And both the Upanishads and Orphisim easily degrade into body-negativity and schismatic idealisms.)

Understanding the grave implications of fleshy logic would inspire the newly initiated, the myste to renounce all but the soul’s needs, pleasures, and sacrifices. A life wherein this recognition of bodily-oriented suffering and renunciation of illusion was absent was compared to “living in a dark cave” in Orphism. Plato’s metaphor of the cave is built upon this Orphic light.

“According to him,” if a person would be attentive to their own blockage of the divine nature, and freely look upon the stain of their soul, then they could abstain from adikia — unjust acts. Dike, the righteous goddess of balance and justice, stood at the Gates of Hades and was “the Primal Way of Things,” the required divine Way to the kosmic harmonia.

Prominent in Orphism is this goddess Dike (Justice), who “shared the same house as Hades.” It was well noted that the divinity of balanced living was the first encounter in the mystic way through the darkness. (The divinity of justice was also the means whereby the disbursement of power from the throne and the wealthy to the citizens was accomplished. Wise laws purified the society and made the city balanced.) Also resonating with the goddess Dike were the underworld “Judges of the Dead,” who weighed the soul’s oaths (juris) and deeds soon after the last breath.

Right and wrong, the simplest of indications, were known by dikaios and ekdikos. Dike, justice, balance, rightness — this divinity brought one next to the divine that is eternal joy.

“They who are righteous beneath the rays of the sun, when they die have a gentler lot in a fair meadow …”

To cleanse the impurities, the adikia, from the soul, the recommended purifications (katharsis) were abstention, restraint, retribution (nemesis), and recompense. Katharsis was a cleansing that included moral acts, right diet, right relations, and right emotions. Fear and pity and anger were to be expressly purged along with the rest of injustice.35 As the pollution (adikia) was countered with right acts, a clearer body and mind would slowly appear, like rinsing a dirty sponge.

A practicing Orphic would make a commitment to forever confront and restrain the adikia, the unbalanced, unjust, addicted modes of dark sympathies– “the unreasonable, disorderly, and violent part of us”.36 Katharsis was a spiritual work, a natural obligation of perpetual cleansing– a labor of refreshment that led to a spiritual clarity.

Many Orphic precepts revolved around the injunction to katharsis, or purification. This katharsis was explicitly described as the disciplined giving of one’s soul to Dike, divine justice.37 By passing through this divine balancing and justice, disciples began to practice while alive what was certain to come in death.

“According to him,” if balance and just ways were practiced while alive, the balancing divinity provided the way for feeling to become free (to the aither). From the Rhapsodies: “And all the others marvelled when they saw the unlooked-for light in the aither, so richly gleamed the body of immortal Phanes [‘to bring primal light’].”38

Aither, “the dazzling light of the sky,” the etheric, was known in the East as prana. Prana, like aither, was associated with the breath and the breath-spirit of all living beings. Embracing the divinity of restraint led the dedicated disciple to the liberation of feeling and an enhanced sensitivity to the all-pervading life.

Instead of unbalanced indulgence and exploitation, the Orphic practiced honor of all living beings, balanced restraint, and harmonious morality– and exclaimed ceremoniously, “Evil have I fled, better I have found.”39 The expressed Orphic promise of this cleansing work was that all things would be released and shed that were not divine and come to the perfection of bliss.40 Divine balance was the just foundation of being “god-infilled” (entheos), and coming to “open eyes” (epopte).41

The fulfillment of desires, the foundation of the universe, the endless rewards of sacrifices, the shore where there is no fear, that which is adorable and great, the wide abode, and the goal — all this you have seen; and being wise, you have with firm resolve discarded everything. — Ka Up I.ii.11

The golden sheets sing the Orphic liberation,

Out of the Pure I come

I have paid the penalty for unrighteous deeds

I have flown out of the sorrowful, weary Wheel of Generation

I have passed with eager feet to the Circle desired

Thou art become god from human.

Through this purification, the nature of the world and oneself became transparent in a single joyous harmony and divine-self realization was possible. In the words of the “poet-scientist” Empedokles, the Orphic torch-bearer and primary disciple of Pythagoras, “From what divine honor, what height of bliss come I, to wander in the land of mortals… I tell you I am a god immortal, no longer a mortal.” 42

Over a century before the birth of Socrates, the “Purifying Priests of Orpheus” became widely influential as they went about the land with their many scrolls and ceremonies, dressed in white raiment, teaching the way, founding communal societies, and purifying and healing the land via their invocation of Dike — suggesting fair laws. (Later charlatans would give such service a bad name and received acrid disdain from Herakleitos, Plato, and the playwrights.)

In the early sixth century (BCE), these priests were giving purifying laws (Dike) to “polluted” (adikia) cities. The most famous of these law-giving purifications was demonstrated by the Sage Epimenides, “one of the ecstatic mystics,” and the “greatest [spiritual] master of all the magically-gifted men.”76 Epimenides came to an Athens in 593 BCE, counseled the poet and statesman Solon in new, balanced laws; he performed rituals, taught openly, and “purified the city.” The three year plague ended, and Epimenides (noted, like Orpheus, for his “prolonged ecstasy”)77 was hailed as the Liberator, Eleutherios. Historians give all the credit of Athen’s leveling and invigoration to the political savvy of Solon, but anciently Epimenides was equally praised for this miracle. It can be presumed that his famous works on politics and ritual were composed then, and added to his widely acclaimed Theogony. (Neither of which have survived.) This spiritual and political balancing between the rich, the poor, and the growing middle class began the inevitable march to full democracy.

The Orphic Acme

The mysticism of the later sixth century was a revival of the spirituality which had begun the century, and this revival was noted at Delphi, Eleusis, Athens, and in all the Dionysian and Orphic cults. Also during this Orphic resurgence, just prior to the golden age, Peisistratus’ theosophical advisor, the genius Onomakritos, collected and recast the Rhapsodes, fully establishing Orphic canon. It is no wonder that Aristotle thought Onomakritos was Orpheus.

Onomakritos’ legacy can also be seen in the marbling of the hillside seats below the Acropolis in Athens for the Orphic story of Dionysus — beginning theatre in the West — and we can easily presume that it was the wisdom of Orphic Onomakritos that opened the Eleusian Mysteries from the privileged royalty to everyone.

Onomakritos promoted Orphism as a high priest and, having the ear of the throne, had the power to dessiminate the refreshed teachings of Orpheus to the colonies. Known as the “minister of cults,” he served to establish Orphism in every Hellenic center. He was a great force in the dissemination of the many Orphic scrolls from Athens to the rest of the Hellenic world. From hometown Athens to Eleuthernai on Crete, to sacred Delphi, to Miletus, Thrace, and to the ashram of Pythagoras at Crotona, brief communities founded on divine realization flourished. Pythagoras’ school is the archetypal, and probably most developed, Orphic renunciate society we know.

The Origins of Greek Theater – Steve Brown

The influence of Orphism can be found in all the pre-Socratics and tragedians, but let it be pointedly repeated that upon the Orphic conception of the immortality of the soul, Plato cast his immortal Forms.80 Even Plato’s cave was an Orphic cave. The grandfather of all philosophy was an Orphic through and through, and his brilliant thought bequeathed the theological and religious thought of Orphism to all Western souls. With this in mind, let us not forget the Upanishadic influences upon the spirituality in the West, influences that transformed ancient Hellas from shamanic ravings into a mystical purity.

Marcus, in Cicero, On the Laws, 2.14.36, with reference to the transfomative power of the mysteries of Eleusis:

For it appears to me that among the many exceptional and divine things your Athens has produced and contributed to human life, nothing is better that those mysteries. For by means of them we have been transformed from a rough and savage way of life to the state of humanity, and have been civilized. Just as they are called initiations, so in actual fact we have learned from them the fundamentals of life, and have grasped the basis not only for living with joy but also dying with a better hope.

Literacy and Theology

“Lord Orpheus” and his disciples founded a new religion in his reformation of Dionysian worship, and it has been said that his was the New Testament to the Olympian Cosmogony. The bardic, spoken word of myth was suddenly superseded by the literacy of Orpheus, breaking the spell of childish belief in the mystic dawn of a new realism.

A religion founded on books, not places, was a relatively new and suddenly widespread manifestation — with Indian, Hellenic, Levatine, and Asian developments. Prior to literacy, the sacred, oral teachings were usually studied only by those who had expressed a great desire and intent to live for (and with and in) the divine, and had been adopted by a qualified teacher. “Upanishad” means the teachings found “at the feet of” the enlightened One.

Through literacy, the intimate wisdom of the oral tradition became common property and scripture flourished. Empowered by literacy, the wall around the palace became the wall around the city and the palaces became sacred Temples. The knowledge reserved for royalty and the wealthy was now open in the Holy Center. The rule of the king was replaced by the rule of law. At the leading edge of culture, adult authencity and mystic revelation replaced the mythic modalities of common membership. Literacy was a revolution.

The written teachings of Lord Orpheus, the Orphika, were effective on a personal level as it broadened the disciple into a deeper being with a higher enjoyment. Socially, it transformed the parental power of the bardic story into a self-empowering literacy, and, in doing so, introduced spiritual authority to the reader.

Orphism was noted for its body of literature, the Orphika. To be an Orphic was a life-long commitment to study a “mass of books,”43 and to feel, reason, and realize the truth therein communicated. To be an Orphic was the epitome of learning. Euripides noted, “They do not eat meat, they honor the rites of Dionysus, they honor many books, and they have Orpheus for their Master.”

It was said that Orpheus was the first and brightest of the theological poets (theologoi),44 whose precepts and principles stepped beyond the mythic mind of belief to a theological nous — an ecstatic, mystic understanding (gnosis).

Prior to the theologoi, only poets and bards (like Homer) mythically sang of the divine, but the theologoi communicated the divine wisdom in both sacred story and logical clarity. Theological authority revised the sacred story with a fresh voice — a voice made true by a lineage of divine realizers (creating scripture in their wake). Theology was the “literal” bridge between mythology and philosophy. Walter Burkett, in his seminal work, Greek Religion, emphasized the transfomative force of this theology, “Orphic literacy takes hold in a field that had previously been dominated by the immediacy of ritual and the spoken word of myth. The new form of transmission introduces a new form of authority to the individual….The emancipation of the individual and the appearance of books go together …”

Blessed Orpheus, the one who possessed “the secrets of Hades,” amended the cosmogony, illuminated the nature of the Underworld, and literally gave the Hellenes a new world view — a view full of mystic and metaphysical understanding. The one who spoke with the Lord of Death gave humankind access to the eternal domain, beyond waking, sleeping, dreaming, and dying. The one who witnessed “stillness in dark places” and the “soul of deep sleep” changed what was understood about the vibrant way of divine awakening.

Orpheus reportedly began his day with an austerity apparently learned from the Indian yogis: rising before the sun and walking to a spot where the sunrise could be seen. In predawn slowness, the yogis would go through a routine of postures to awaken and harmonize the body. Breathing practices would inspire the pranic, etheric energies and feelings to rush through inward and outward pathways. As the life-force vaulted awake and sunlight broke forth, the practitioners looked into the horizon sunshine, letting the soft star relax into their sight. Closing the eyes and breathing inward with skyward feelings, the yogis would swoon upwards to the creative bright star at the mystic origin of the body and all things. Orpheus was noted for this practice.

Orpheus, the “god-infilled Initiator,” founded western spirituality by blending Upanishadic enlightenment with the Homeric/Hesiodic religiosity of the Hellenes. To the spatial cosmology of Hesiod, Orpheus added temporality: the knowledge of destinies and the wisdom of associating with divinity. With an empowering Orphic step forward, mythos transformed to hiero logos, or sacred and moral story, then to mystic ek-stasis, ecstasy — the evidence of divine intercourse. Ecstasy gave birth to the immortal soul (psyche), speech about the blossoming being (physis), and divine reason (theologos). Theogonies flourished, all inspired by the prophet Orpheus. “The legends of Orpheus are sacred song, the other world, and the ennobling a man by song and transcendence, by the mysteries and the divine suffering of the founder.

The feeling, breathing psyche of Hellas was called atman in Vedic India, and both are translated into English as soul. It was this emphasis of soul over mere body and mere sentiment that formed the soulful way to immortal happiness — both in the Upanishadic East and the Orphic West.

Orpheus was well-known for his soulful tempering (sophrosyne) of the raving rites (bacchos). By the advent of sophrosyne, Orpheus incarnated the dynamic dance of still Apollo and energetic Dionysus in person. His power was the dynamis of the two gods in a single being, and he was likened to the Temple at Delphi itself (where the Hellenes housed Apollo and Dionysus together).

It has been said that Delphi itself was only fully baptised and empowered with the Orphic “Dionysation of Delphi.”51 Indeed, upon the lesche wall of Polygnotos at the Delphi was Orpheus revealing the realm of Hades.52 And also there, upon a recovered metope is Orpheus with his lyre assisting the Argonauts, giving the adventurers more power than brute force could deliver, more power than even clever cunning could conceive, more enchantment than the call of sirens. With his heart-lyre, Orpheus even calmed the waters of the stormy sea, and called down sleep upon the eyes of the untamed dragon which guarded the Golden Fleece — all through his “god-infilled” joy.

Orpheus, the mad priest of love, was far more than the mythical and magical minstrel who could charm and move men, gods, trees, and even stones. Rather, his songs, legends, and myths belong to a body of spiritual instruction, and, together with abundant fragments of the Orphika, it seems obvious that Orpheus was a powerful spiritual teacher — a communicator of wise liberation with a wide impact.

As the “Reformer,” Orpheus recast the cosmogony and cosmic order, such that the kosmos, instead of coming out of Darkness or Night, was first born of Primal Light, Self-Existing Brightness (Phanes), and Love — from which the Gods, Goddesses, and humanity would come.

Amending the spatial “Hesiodic” framework with the fateful sense of time-flow, Orpheus challenged his followers to comprehend the destiny of their choices. According to him, Chaotic Dark is illumined by the seed of spiritual Love. More important that all other cosmological revisions, Orpheus added Love, Eros (known also in its lighted sense as Phanes). Eros joined Night, embracing even Chaos (“gap”, “void”) with divine communion. Thus, Eros, Night, and Chaos were known as “Orphic powers.” The new Orphic cosmogony carried a challenge for the moral and immortal soul.

The orthodoxical Aristophanes captures for us the common Orphic cosmological description:

It was Chaos and Night at the first,

and the blackness of darkness,

and Hades’ broad border.

Earth was not, nor air, neither heaven,

when in the depths of the womb (delphi)

of the dark without order

First thing first-born

of the black–plumed night was a wind-egg

hatched in her bosom,

Whence timely with seasons revolving again

sweet Love burst out as a blossom

Gold wings gleaming forth of his back (Phanes),

like whirlwinds gustily turning,

He, after his wedlock with Chaos,

whose wings are of darkness,

in Hades broad-burning

For his nestlings begot him the race of us first,

and upraised us to light new-lighted.

And before this was not the race of the gods,

until all things by Love were united:

And of kind united with kind

in communion with nature, the sky and the sea.

The blessed are Brought forth

and the earth and the race of the gods are blest and everlasting.

The Orphika, or the body of Orphic teaching, was fully developed by the sixth century, and was known in two forms: “Sacred Stories” (Heiros Logos) and “Rhapsodies.” The rhap-sodes, or “song stitches” were philosophically and etymologically resonant to the “thread” of Hindi “sutras,” and also the etymological root of today’s medical “thread,” “sutre.” Orpheus’ threads, sodes, were full of flow (rhea), weaving the fabric of truth, musing the revelation, dancing upon a point again and again in joyous demonstration. The rhapsodies were the first teachings to be known as the wisdom of the very divine, theo-logos.

As a spiritual teacher, Orpheus described the Bright numinous divinity that can be found in both the death process and in the mystic passage through the dark unconsciousness, revealing Elysium, “the abode of divinity.” As a rationalist, Orpheus elucidated the evolutionary structure of the kosmos. He suggested that life came out of “water and slime warmed by the sun,” then evolved through higher animals until Life recognized itself in the purified human form. As a realist, he required the understanding of suffering rather than belief in myths in order to serve one’s attunement to the unlimited. He rearranged the Western conception of the afterlife, taught palingenesis (reincarnation of the soul), and spawned a soulful emergence of individualism.

The rising individuality transmitted by this Upanishadic/Orphic gift of soulful immortality began a new turning of the world, and civilization was refreshed and moved forward. Mythological modes of orientation were exceeded by theosophical doctrines, where insight outshined belief. Speculative theology and prophetic speech illumined the Dionysian faith in the ecstatic, theological birth of reason. This divine knowledge is gnosis&endash;linked etymologically to Vedanta’s jnana, “divine knowledge,” and also to Arabic jnna, “divine madness,” from which we get “genius”.

Orpheus’ transformed and transforming influence went down the west coast of Asia Minor to Ionia and became physics and metaphysics; his cosmogony and mystic gnosis went south to Athens and became the Rhapsodies, philosophy, theatre, and democracy; his enlightened joy moved west to Italy and emerged in harmony, mathematics, community, Stillness, and Being without genesis. The influence of Orpheus and Orphism can hardly be overstated.

Orpheus could be called the first Dharma-Bearer to the West, and philosophy’s first light. Indeed, the soul of Orpheus can be found in Anaximander’s necessity and justice, in “Law-Giver” Parmenides’ poem of Being, in Herakleitos’ Logos, and in Socratic ignorance, epistemology, and care. Then Plato’s metaphysics gave it a classical form which has lasted for thousands of years. To look out of your eyes, feeling that you are a soul, being mysteriously led to the Light, is to see the effect of Orpheus now.

Listen!

It has been suggested that the word Orpheus is rooted in orfne, “chthonic dark.” If this is true, then it can be said that accepting and knowing the darkness is coincident with light. This stillness in dark places and light-piercing-the-darkness (Hindi gu-ru) is the herald-call of human maturation. Blessed Company awaits all who heed the invitation.

It has been suggested that the word Orpheus is rooted in orfne, “chthonic dark.” If this is true, then it can be said that accepting and knowing the darkness is coincident with light. This stillness in dark places and light-piercing-the-darkness (Hindi gu-ru) is the herald-call of human maturation. Blessed Company awaits all who heed the invitation.

Myste also implied that one should close the mouth and listen to the word of One who is Awake beyond the dreams of Hades. Myste! (Listen!) When asked why new initiates to his company had to keep silent and only listen to the Master for five years, Pythagoras answered, “Like cloth is whitened before dyes color it.”

To receive initiation (myste) was to accept adoption by a god or master — it was to be re-born to another fate beyond your common destiny. To submit to the grace of a divine being and receive his or her blessings was what was meant to be a myste (myste in Latin is also translated as initiare). Myste is rooted in myeo, “to close,” and the social suggestion is to close your mouth and keep secret the mysteries, like intimate knowledge. Myste carries the implication of “secret,” a heartful respect for initimate, mysterious “knowing”. Listen to the Testament of Secrets and receive the Initiation of a Master!

This sensitivity to the lineage of wisdom was the school of character, to answer the noble (ariste) call of excellence (arete). Those who answered this call harvested the “wisdom of suffering” (paqei maqos). (Otherwise, suffering just leads to more suffering.)

Arise! Awake! Approach the great and learn. Like the sharp edge of a razor is that path, so the wise say, hard to tread and difficult to cross. — Ka Up I.iii.14

Closure is also the motion of restraint, of tempering (sophrosyne) and taming the outgoing energies of a dissipated life, likened to taming a steed. To be a myste, an initiate, was a great and honored challenge to divine living. Intimacy, listening, discrimination, and temperance characterized the life recommended by the Master of the mysteries.

If the buddhi, being related to a distracted mind, loses its discrimination and therefore always remains impure, then the embodied soul never attains the goal, but enters into the round of births.

But if the buddhi, being related to a mind that is restrained, possesses discrimination and always remains pure, then the embodied soul attains that goal from which he is not born again.

A man who has discrimination for his charioteer, and hold the reins of the mind firmly, reaches the supreme goal. — Ka Up I.iii.7;9

The myste understood the necessity to listen, not just to the Master, but to their stream of experience. To develop sensitivity to one’s participation in the play of experience was the quintessence of the myste’s “purifications.” One who listens, hears. Listening to the unbalanced, out of tune actions, one is graced with sensing the resonant truth. Indeed, the mystic, esoteric order of Pythagoras was referred to as the Akoustomaki — “the Hearers.”

The self-revelations encountered in the ascetic way Orpheus recommended empowered the myste to a realistic self-understanding. Similar to the practice of dukkis, or the First Noble Truth of the Buddha, the foundation practice of the mysterious Orphics fostered a sensitivity to the self-created nature of suffering. Practitioners East and West were called to listen in order to hear.

What is here, the same is there; and what is there, the same is here. He goes from death to death who sees any difference here. — Ka Up II.i.9

The Spindle Destiny

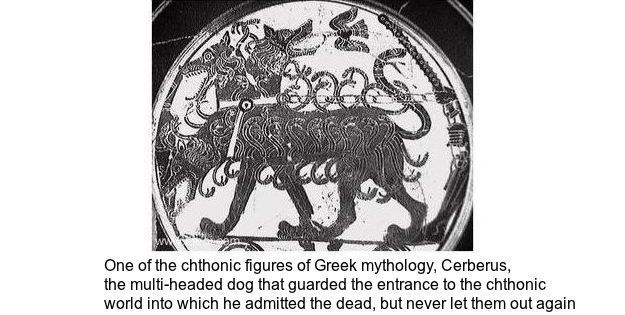

Orpheus, “the great realizer of Dionysus,” came “full of god,” and proclaimed the secret way beyond the usual destiny and death. His mythic description of the underworld contained a description of the passage beyond the prisons of life and afterlife, as well as liberation from the mechanics of destiny.

Well then, I shall tell you about this profound and eternal Brahman, and also about what happens to the atman after meeting with death. — Ka Up II.ii.6

According to Orpheus, lord of the mysteries, the soul comes into the body with the first breath, and when the body expires, the psyche, breath or spirit no longer animates the body. Life flows out of the body, dissolving flesh and thinking — as the “shade” emerges from the top of the head (or out of the mouth with the last breath). Hermes, the “Crosser of all Boundaries,” comes with his magic staff to take the “shade” or soul (psyche) on its journey. There is the inherent cognition that the staff of Hermes is the mystical path up and out of the body, and likewise there is the recognition that the flow of death is the river Styx.

After the body and mind are left behind, the only quality that remains is one of thirst.53 It is the thirst or need that moved one while alive to be fulfilled. Now the yearning is without an object; neither wealth, nor adoration, nor sexuality, nor glory, nor pleasure of any kind obscures the naked unfulfilled need itself.

Thus possessed of a naked thirst, the tour of the previously un-seen (a-des “Hades”) begins. First, Dike and the Judges of the Dead judge or weigh the oaths (juris) the souls made during life to see how well oaths were kept:54 this weighing was known as psychestasis. (This is essentially identical to the Egyptian description of balancing the soul’s heart against a feather.)

Coming to depth of self-knowledge too late, most souls are tormented, confused, and driven about the Underworld. Pindar sings of this psychestasis after death,

The guilty souls of the dead straightway pay the penalty (for their sins) here on earth, and the sins committed in this kingdom of Zeus are judged by the One beneath the ground.

The “shade” wanders further down into the muddy darkness of Hades and soon comes upon the Pool of Lethe (Forgetfulness). Those souls whose habit of immediate satisfaction dominated their heart while alive desperately throw themselves upon the shores of Lethe to satisfy their driving thirst.

Drinking from the waters of Lethe, their need is satisfied, but they forget who they are and wander forever aimlessly and in confusion throughout the Underworld — in the muddy, flatland of Asphodel — where neither trees nor any of the fruits of the earth appear.

Satisfying new thirsts by drinking from the river of Indifference (“been there, done that”), un-lighted souls eventually gather in the meadow of Tartarus. There, they journey the Milky Way to the celestial axis of Ananke (Necessity), where her daughter, the Fate Lachesis (who presides over lots), gave each soul a “daimon appropriate to his choice.”

To understand the interplay of the Fate Lachesis and the soul is critical. The soul must choose its daimon, its character,56 which Lachesis then assigns to the soul as his or her “guardian and the fulfiller of his choice.” Thus, the soul and Fate, self and luck, free will and determinism, future choices and the “tragic tense” share responsibility for the fabric of life. (And this leads to the later-in-life wisdom of knowing what you can and cannot change.)

The daimon leads the soul to another daughter of Zeus and Necessity, the Fate Clotho (the spinner) — who turns the spindle to ratify the destiny that the soul got “by choice and by lot”.57 The soul then receives the “inflexible” news of his or her eventual atrophy and termination from the final divine daughter, Fate Atropos (“she who cannot be turned”), “who makes the web of destiny irreversible.”

As the three daughters of Necessity, together with the sirens (lit. “to bind”) sang the fate of the soul in the music of the spheres, souls were again brought before the throne of Necessity. The way to rebirth began and ended with Necessity. At the knees of Necessity rested the Spindle which governed the movement of incarnation into the kosmos — arising in concentric spheres or “whorls” — according to the fates of necessity.

The souls destined for reincarnation were made to drink again from the waters of Lethe,58 so that their recollection of their previous life and Underworld experience dimmed and was forgotten. Thus rendered lethargically unconscious, souls are thrust into a new incarnation, to try again and learn the wise way (philosophia) to divine reason (nous) and thereby immortality. To be liberated from the mere “cycle of generation” was the lesson and challenge by which the transmigrating soul (metempsychosis) would pass out of the dreamy afterlife into birth and breathe again.59

Some enter the womb for the purpose of new embodiment, and some enter into stationary objects — according to their work and according to their knowledge. — Ka Up II. ii.7

Upon the first breath, each soul is imprinted with its “spindle destiny,” the implied fate of everything surrounding the newborn — mother, father, family, village, language, culture — even the sun, moon, and stars. (In India, this spindle destiny is known as karma).

To penetrate the spindle destiny was the great challenge in moving beyond “the tomb of ordinary destiny” to a free divinity. Such penetrating authenticity was the trademark of the theologoi. In the words of Plato, the theologoi were “divine men, who may be expected to know the truth about their own parents.”60 (Here we can also recall Herakleitos’ injunction, “Do not be the child of your mother and father.”) And Plotinus made this quite clear (11.3.9), “In every moment you have a choice: you can live your Spindle destiny or you can live authentically.” To live authentically is to outshine the spindle destiny; to live authentically is to outshine the mechanical reaction in responsive mutuality; to live authentically is a kind of deathlessness, even while all forms pass away.

From the Icy Halls of Hades to the Riches of Pluto

With the advent of Orpheus, death ceased to be a grey copy of life on earth like it was portrayed in Homer and the Near East mythologies. With mystic Orphism, death became another moment in an eternal process whereby one can look up from the pool of changes and choose to be already awake.

On the Orphic sheets of pure gold, or lamellae, we find awake awareness about the transcendence (or utter acceptance) of feared Hades and death, and how to be awake in the afterlife, and what that means for living now. We read the injunctions to a divine life here, injunctions on how we should live to best serve the immortal soul. The rhapsodies of Orpheus not only taught purification and balance, they empowered the soul to choose paradise while living — as well as when the body falls away. From the lamellae,

And the Kings under the earth will pity you,

and they will give you to drink from the lake of Remembrance.

And it is a thronged road you are setting out on,

a holy one along which other famous initiates and bacchants are proceeding.

Thou shalt find to the left in the House of Hades the Pool of Forgetfulness

To this well-spring do not approach,

Look up to the white poplar

There find another water-source, the Lake of Remembrance.

Cool water flows there, surrounded by Guardians.

Finding the Pool of Remembrance, approach and say:

“I am the offspring of Earth and starry Sky,

“I am parched with thirst and am dying;

“Quickly give me the cool waters flowing forth from Remembrance.”

Those that drink of the waters there go to the same immortal place as the Heroes and also take on the mantel of divinity.

This passage to Elysium was discovered and cultivated in the ancient mystery schools, giving the initiated myste great joy while alive and imparting a mysterious understanding of the process of death. For the initiated, the privilege of Elysium was transferred from the province of the afterlife’s Underworld to the living on the surface of the Earth.72 This knowledge became widespread under the zeal of Onomakritos — when he opened the mysteries at Eleusis to every free Hellene. Suddenly, everyone had access to the experiential basis of the propagandized cosmogonies.

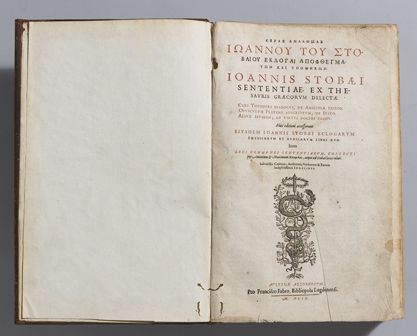

This point is clearly illucidated for us by Stobaios:

The soul [at the point of death] has the same experience as those who are being initiated into the great mysteries . . . At first one wanders and wearily hurries to and fro, and journeys with suspicion through the dark as one uninitiated: then come all the terrors before the final initiation, shuddering, trembling, sweating, amazement; then one is struck with a marvelous light, one is received into pure regions and meadows, with voices and dances and the majesty of holy sounds and shapes; among these he who has fulfilled initiation wanders free, and released and bearing his crown joins in the divine communion, and consorts with pure and holy people. 73

It is worthy of note that the word Hades is from Aides (a-des), meaning not-day, not bright, dark un-conscious, fearful un-known. Its qualities are of shadowy, lazy forgetting, dark and fearful not-knowing; fearful not-accepting; lamentful, un-fulfilled thirsting; shortsighted foolishness; and lethal arrogance. The domain of Hades holds the grave unknown and the unconscious dark.

Interestingly, the Lord of the Underworld was also referred to as the “Most Gracious One,” since He received every soul with open arms. An Orphic hymn invokes Him:

Pluto! Subterranean is your dwelling place, O strong-spirited one…

All-Receiver, with death at your command, you are master of mortals… You delight in the worshipper’s respect and reverence. Come with favor and joy to the initiates, I summon you.74

When the darkness was illuminated by purification and faith, and the unconscious was no longer resisted or covered, when fear, pity, and anger allowed themselves to be known, seen, and accepted, then feared Hades became known as luminous Pluto, the god of riches. Thus it is said, “Where one stumbles, there one finds the treasure.”

Pluto is the name for Hades when his darkness is lighted, revealing the jewels and gold beneath the earth. The Hades-to-Pluto transition is the first hope of every soul.

The power and transformation of Hades held a mighty power in the minds of the ancient wise. From Zeus-Chthonios to Dionysus-Chthonios, from the Kathartic Asklepios to heroic Herakles, from sweet Persephone to the mysteria of Apollo, Dionysus, Eleusis, and Orpheus, Hades was a divinity with which to be reconciled and combined in order to be fully alive and to freely die.

In the words of Pindar, Blessed is he who hath seen these things before he shall pass beneath the ground. He knoweth the end of life, and he knoweth this god-given origin.

This transformation from dark trouble to gracious riches was emphasized by Orpheus as he repeated the already famous saying, “like a [goat] kid who has fallen into milk.” The presumed tragedy and fear was suddenly found to be a blessing and overwhelming joy.75 Incarnation is not a grave matter only — it is an unfathomable blessing, the ecstatic place of divine intercourse.

Orpheus and Eurydice

Orpheus’ well-known passage through Hades’ Underworld for his Eurydice transmits the spiritual lessons on the power and the limits of human love. A spectrum of self-knowledge graces those who examine the kinds and stages of love.

Orpheus’ joy was clearly no ordinary affection. Indeed, this heart-joy was to be distinctly seen as being beyond common sentiment. His was the truly powerful love that mastered the urgent animals, the cyclical elements, the sentimental sirens, and even the problem of death. But still that powerful love had a limitation, the requirement of the other. So long as the Beloved is other, the dyadic lovers will be shattered by death. It is this dyadic tension of self and other, I and Thou, that possessed the mythical Orpheus to turn too quickly.

The lesson of Eurydice is the lesson on balancing the three loves: sentiment, real love, and spiritual love. This three-folded spectrum of heart-knowledge was the context wherein the Orphic located his true self-knowledge (confluent with the three-fold way of purification, communion, and ecstasy). To grow beyond the limits of object-dependency, human love, and religious deification is the Orphic fruit of understanding the dyadic error. This purification of sentiment into real love and the maturation of real love into divine love was the deeper lesson learned from Orpheus, Eurydice, and Hades.

Orpheus’ mature demonstration of real love beyond brawn and sirens revealed the strength of real love in contrast to the ordinary weakness of immature sentiment. Orpheus’ eventual loss of Eurydice revealed the limitation of human love: as long as the Beloved is Other, the love will be shattered. By the lesson of Orpheus and Eurydice, we are called to grow beyond sentiment and even human maturation into divine love. (Rumi once summarized his life: “I was immature, I matured, I was consumed.”) Sentiment is transformed by katharsis into real love, and human maturity is further purified by the “invasion of divinity” (entheos) to the soulful love of the divine.

The three loves were the three stages of the soul: sentiment, psyche, and divine self-realization. The deepest soul which witnesses the three common states — waking, dreaming, and sleeping — comes into its own in death, but can be sensed in deep sleep, and learned in mystical self-realization.

Later Christian theologians would echo this maturation of love via the ancient Hellenic words eros and agape. Eros, in the narrow Christian view, was the limited love of sentimental promises and hopeful fulfillment; agape was the free love of self-giving, soulful sacrificial, sacred love. (Eros to the ancient Orphic ranged from the erotic multiplicity to the mystic’s heart thrill of kosmic unity.)

When all the desires that dwell in the heart fall away, then the mortal becomes immortal and here attains Brahman.

When all the ties of the heart are severed here on earth, then the mortal becomes immortal. This much alone is the teaching.

The inner Self, always dwells in the hearts of men. Let a man separate Him from his body with steadiness, as one separates the tender stalk from a blade of grass. Let him know that Self as the Bright, as the Immortal — yes, as the Bright, as the Immortal.

Having received this wisdom taught by the King of Death, and the entire process of yoga, Nachiketa became free from impurities and death, and attained Brahman. Thus it will be also with any other who knows, in this manner, the inmost Self. — Ka Up II.iii. 14-15, 17-18

The Mystic Tour

Orpheus revealed another possibility beyond the tomb of being given to one’s spindle destiny: the souls who enjoyed “the pleasure in the keeping of oaths,” and who were made sufficiently light by the divinely oriented life were not lost in vast chasms after death, not mired in the muddy flats of Tartaros, but were given avenue to the Paradise of Elysium, “eternal drunkenness,”61 the Islands and Company of the Blessed.

Learning the passage through the echoing halls of icy Hades was of utmost importance to the Orphics — for then the soul was liberated from fear, death, and all the spindled labors on the wheel of birth.62

Souls who were initiated into divine knowledge while alive knew not to settle for the first satisfaction that came along.63 Instead, they looked away from the waters of Lethe and turned their eyes upward and looked for the white poplar tree.64 For those seriously prepared, the rapture of this transmission mysteriously illuminated the nervous system of the devotee as a white tree of life — seen internally in mystical vision as the dual-snaked herald of Hermes, the “Crosser of All Boundaries.” This mystical vision of the white tree and nectarous soma was purported to be seen in the process of death as the way whereby one finds the liberating Pool of Remembrance.

This is the eternal Asvattha Tree with its root above and branches below. That root ball, indeed is called the Bright; That is Brahman, and That alone is the Immortal. In that all worlds are contained, and none can pass beyond. This verily is That. — Ka Up II.iii.1

The soul travels up the white tree, and comes upon the Pool of Mnemnosyne, the waters of Heart Remembrance in the center of the brain. Here, desire is finally vanquished by the sweetest of nectars, quenching and anointing every human and evolutionary thirst with baptismal sublimity.

Rising in radiant fullness from this divine pool, the wings of the Caduceus unfold within the mystical brain, crowning one’s own heart-flight into the blissful paradise.

Let us listen again to the songs of Pindar, singing across the millennia the vision of Elysium that Initiates enjoy, For them in the world below the sun shineth in his strength…and in meadows red with roses the space before their city is shaded with trees of frankincense, and is laden with fruits of gold. Some of them take delight in horses and in sports, and some with games of draughts and with lyres, and among them bloometh in perfection with the flower of bliss.

Over the lovely land fragrance is ever shed, as they mingle all manner of incense with the far-shining fire on the altars of the gods…

Flowers gleam bright with gold, with glorious trees, and wreaths intertwine their arms and crown the head.66

This “crowning” was known in the Orphic schools as stephanos, and was ceremoniously celebrated with garlands of laurel. Orphics were noted for their laurel crowns, indicating someone who had drunk from the divine Pool of Heart Remembrance, and had thus awakened into the consciousness of the divine domain. (In later times, the laurel indicated someone who was merely drinking freely or simply drunk.)

The top ball of the caduceus is the mnemonic pool of nectarous soma at the pineal center of the brain (in India, the ajna door), and the staff and snakes are the spine and nervous system harmonies (Anatomically, the spine is represented by the straight staff, and sympathetic and parasympathetic portions of the nervous system are represented by the interwoven snakes. In India, mystics call these the sushuma, ida and pingala). The Caduceus is an image of the nervous system in its native and divinely open state, the balanced soul perfectly alive.

In mystical ascent within the heart’s thrill, one follows the white tree upwards and finds the rapturous pool. According to the mystic teachings, as we rise from the nectarous Pool of Mnemnosyne, the vision of Bright Elysium’s spirit-filled paradise satisfies the soul, allowing the heart nectar to light the ventricles of the brain — where their lightedness appears as the wings within. This mystical vision, felt and seen in the sublimnities of rising and rapturous love, has given cause for religious traditions (from Orphic mysticism and the traditional yogas of India to the Chinese Secret of the Golden Flower) to value the crowning terminus of the nervous system as the very divine.

He, the Supreme Divine Person in the Heart, who remains awake while the sense-organs are asleep, shaping one lovely form after another, is indeed the Pure; He is Brahman, and He is Immortal. All worlds are contained in Him, and none can pass beyond. This, verily, is That. — Ka Up II. ii. 8

For the mystic Orphics, the divine pool of Mnemnosyne or Remembrance at the entrance to Elysium was found in both mystical ascent and in the process of death. They loudly noted that to drink the waters of Remembrance, one must forsake the lethargic waters of Lethe. For the Orphics, to forsake the lethargic satisfactions of bodily pleasures and remember the ambrosial satisfaction of the soul’s deepest thirst is the gateway to Paradise, or “eternal god-intoxication” (Vedanta, samadhi), whereby death is “swallowed up in victory,”69 and the soul falls into “the unbroken radiance of divinity”.

The Truth of Alethia

The understanding of the spiritual process whereby one turns up from Lethe (Forgetfulness or Coveredness) can be appreciated in the ancient Hellenic word for “truth,” alethia. In this most salient of all philosophic words, we find a deep understanding of the process of initiation revealed in the Orphic schools. Alethia, a-lethia, a-lethe, not Lethe, not forgetful, not covered, not lethargic, not lethal — alethia, revelatory Truth.

Understanding the lethargic underworld and understanding the immortal worlds is just a metaphor for understanding the real truth of existence now. Orpheus’ theological understanding of reality can be found in the insight of the lovers of wisdom, the philosophers.

For the ancient lovers of wisdom, Lethe was coveredness and forgetfulness, while its opposite, alethia, was the revealing truth. Truth was to look up from the ephemeral pool of driven-self-obsession. Truth, in this regard, is in no way limited to the factual or material; the implication of alethia was closer to conscious understanding, divine revelation, noble being; rememberance, and paradise. Alethia’s uncovered, un-forgetful, un-lazy quality bespeaks of the wise ones who look up from themselves, who look up from the leth-argic pool of lethal self-satisfaction. Truth is to un-cover, look up, and remember the perfect relatedness and singularity of divine existence.

The Death and Limitations of Orpheus

By the fifth century, the religion of Orphism as a whole had lost much of its purity and discrimination, and was scorned for its disdainful fakery and indulgent illusions. By the late fourth century, differences between the representations of Orpheus and Apollo disappeared, and the legend of Orpheus faded into the mythological background. Mythic Apollo harmonized with the inspired poet, until they became one.

Mythologically, it was reported that the wild women ravers of Dionysus became mad at Orpheus’ allegiance to Apollo and tore Orpheus apart — in the manner that the god Dionysus had been ripped asunder. Apollo’s Muses gathered his body, and his head was said to have survived intact, still spouting oracles (nekymanteion, literally the “manna of death”). And it was repeated again that the process of the mysteries and the process of death are the same.

While an inner circle of serious disciples nurtured the spiritual force for centuries, Orphism became mostly known for its relentless search for purity, for its body-distrusting disharmony, for its schismatic and schizophrenic approach to life. Instead of the blissful unity of god-infilling, Orphics were obsessed with solving the problem of existence!

A thousand years after Orpheus tamed the mysteries, in the post-Plotinus darkness, and after the Imperial forces of the Roman Christians snuffed out the sacred rites, magicians incanted the name of Orpheus to empower a potion,82 and the Fields of Elysium was a heaven found only after death, or in some new, future age. Orphism was certainly dead.

Western Orphic Presumptions

Our gifts from the Orphic tree are many. It is the Orphic Dionysus who transformed from being Zagreus, “torn-apart,” into a pleasure-loving goat, and then into a god — and, by this story, Western theatre was created. Orphism gave us theology and the theological bridge from mythology to philosophy. The Western presumption that there is an afterlife of consciousness and retribution where the soul makes conscious decisions is Orphic. Likewise, our presumption while alive that we are a “soul”, a psyche within, “behind blue eyes”, is profoundly “Orphic”. That we are an immortal soul inside and engage the flow of time as a morality play of wisdom and destiny could be described as “Orphic”. The idea that the force of love exceeds the binding power of sirens is “Orphic”. To feel the power and the limitation of human love is an “Orphic” issue. To view the ordinary round of life as cavelike is Orphic, as is to think of the light outside the cave as divine. To conceive of heaven or eternal wholeness as wise and pleasurable is “Orphic”. To follow the caduceus within as a mystic ascent of rapture is “Orphic”.

On the negative side, to have a negative relationship to the body is “Orphic”. In a similar vein, Orphism was pointedly misogynistic — until the reformation of Pythagoras. To turn away from life is Orphic. To turn away from the world as a requirement of spirituality is Orphic. Orphism suffers all the limitations of religious and mystical paths to God: a dualistic conceptualization that this world and the body are bad, and the solution to human suffering is renunciation of this world and the body and to give your attention to the soul only. In accordance with this negative view of this world, it is from Orphism, via Christianity, we have inherited the tormenting afterlife in hell.

While there is much wisdom in this view, the truth is not schismatic. Even the Orphic realization was “to find oneself already in the Fields of Elysium,” and Orpheus himself is said to describe realization as beginning “the years of pleasure.” But while the realization speaks for the non-dual, unitive joy, the Orphic teaching is dualistic and schismatic, revealing its immaturity in the history of religious thought.

This negative view has contaminated Western thought, and was joined by the contamination of the Christians, and is only recently begun to abate. To revisit Orphism is to revisit this negative view present in the structure of suffering souls.

Of course, what is presented here is the best and highest collection of Orphic thought, probably not all present in any given period, except in the time of the Master of the Mysteries.

I have seen and been served by such a One in the form of Avatara Adi Da. It is because of his initiation and transmission that I reconstruct Orphism in spiritual terms. Through this recounting of ancient spirituality, I can properly introduce a poem of Avatara Adi Da:

I served to Priest the Pharaohs

in an ancient time

I have always lived to serve the Holiness

to kings and lords,

to those who make the rule among men.

I stood behind the battlers