A Beezone Discussion with Professor Yates: Tracing the Evolution from Spirituality to Rationality

***

Preface

This discussion is a creative exploration inspired by the interactions Ed Reither of Beezone had with ChatGPT, based on his readings of Frances Yates’s Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. While the dialogue between Beezone and “Professor Yates” is fictitious, it is firmly grounded in real exchanges conducted over time.

This piece demonstrates the enormous potential of AI for educational purposes, showing how artificial intelligence can serve as a tool for deepening understanding and fostering intellectual exploration. However, it also emphasizes that AI is not a substitute for personal educational research. Developing one’s own critical thinking, learning capabilities, and engagement with primary sources remains essential. AI can assist and enrich the learning process but should complement, not replace, the foundational efforts of inquiry and scholarship.

Introduction

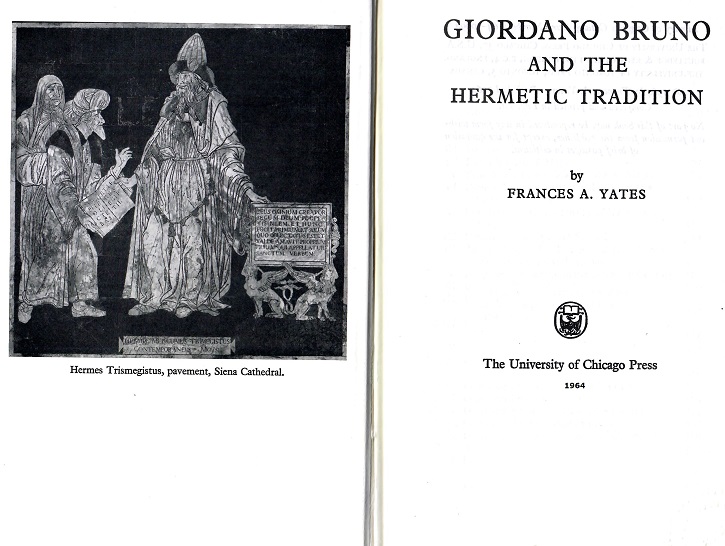

The transformation of authority from spirituality to rationality and eventually to modern science represents one of the most profound shifts in human thought. This evolution can be traced through figures like Augustine of Hippo and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, both of whom operated within the Catholic tradition yet reflect vastly different attitudes toward faith, reason, and the exploration of reality. In this discussion, Beezone engages with “Professor Yates”, the real author of ‘Giordano Bruno and the hermetic Tradition’, to examine this transition and its implications for today’s reliance on science as a dominant worldview.

Beezone: Professor, let’s start with the foundation. In Augustine’s time, the Church was the central authority on truth, with reason serving faith. How did this shape Augustine’s critique of practices like Hermetic magic?

Professor Yates: Augustine lived in a time when the Church’s authority was deeply tied to maintaining a spiritual framework for understanding the world. For him, practices like Hermetic magic—which sought to manipulate natural forces through invocation of spirits or daemons—were not merely misguided but dangerous. These practices threatened to undermine the singular truth revealed through Christian doctrine. Augustine’s critique, particularly of figures like Hermes Trismegistus, reflects his concern that such “magic” diverted attention from divine worship and opened the door to idolatry and demonic influence.

Beezone: So, for Augustine, even the pursuit of understanding hidden forces in nature was problematic if it was outside the Church’s framework?

Professor Yates: Precisely. Reason and inquiry were permitted only insofar as they illuminated and defended the truths of faith. Anything that appeared to operate independently of divine authority was suspect. This is why Augustine’s view contrasts sharply with the Renaissance thinkers who later saw natural forces as a reflection of divine order, accessible through reason and study.

Beezone: That brings us to Pico della Mirandola. By his time, the rediscovery of classical texts and the rise of humanism began shifting how knowledge was pursued. How did Pico navigate this tension between faith and reason?

Professor Yates: Pico was remarkable in his attempt to harmonize these elements. His Nine Hundred Theses sought to show that all philosophical and religious traditions contained fragments of divine truth. By presenting these propositions to the Pope, Pico positioned his work as a synthesis rather than a rejection of Catholic orthodoxy. However, his emphasis on human potential and rational inquiry marked a clear departure from Augustine’s strict subordination of reason to faith.

Beezone: Would you say Pico’s approach was more inclusive, even universalist?

Professor Yates: Absolutely. Pico’s vision was rooted in the belief that human reason could bridge gaps between faiths, philosophies, and even the mystical and the empirical. This inclusivity allowed him to explore traditions like Cabalism and Hermeticism within a Christian framework, arguing that they complemented rather than contradicted Church teachings. His work exemplifies the Renaissance shift toward intellectual autonomy while still respecting religious authority.

Beezone: This seems like the start of a larger transformation. How did the Church respond to the growing prominence of reason and, later, science?

Professor Yates: The Church initially embraced reason through movements like Scholasticism, which sought to integrate Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology. However, as rational inquiry evolved into empirical science, tensions emerged. Figures like Galileo Galilei and Descartes challenged the Church’s authority by asserting that natural phenomena could be understood independently of divine revelation.

Beezone: This tension eventually led to a shift in authority from religion to science, correct?

Professor Yates: Exactly. By the Enlightenment, the scientific method—grounded in observation, experimentation, and reason—had supplanted the Church as the primary arbiter of truth. This transition reflects a gradual secularization of inquiry, where phenomena once attributed to divine or spiritual causes were increasingly explained through natural laws.

Beezone: And today, science is often seen as the ultimate authority on reality. Would you say this is the culmination of the process that began with figures like Pico?

Professor Yates: In many ways, yes. Pico and other Renaissance thinkers laid the groundwork for a worldview where rationality and empirical evidence became central to understanding the universe. However, the modern reliance on science as the sole authority raises questions about whether we’ve replaced one form of dogma with another. The pendulum has swung from faith to reason, but perhaps there’s still room to integrate these perspectives more holistically.

Beezone: That’s an intriguing thought. Could we learn from figures like Pico to bridge science and spirituality in a more balanced way?

Professor AI: Pico’s universalist approach remains relevant. His attempt to unify diverse traditions and see rationality as complementary to spirituality offers a model for navigating today’s divide between science and religion. Acknowledging the limits of both frameworks could foster a more integrated understanding of reality.

Conclusion

The evolution from spirituality to rationality and science reveals a dynamic interplay between faith, reason, and authority. Augustine and Pico, as Catholic figures from vastly different eras, embody this transition, illustrating how the Church both shaped and responded to the rise of rational inquiry. Today, as science assumes the role of ultimate authority, their examples remind us of the ongoing need to balance empirical understanding with spiritual insight. By revisiting their ideas, we may uncover ways to reconcile these often-divergent paths in our pursuit of truth.