The following is Beezone’s look into an ‘incident’ with M.S. Merwin – U.S. poet laureate twice – his girlfriend Dana Naone and Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche in 1975.

The “Great Naropa Poetry Wars” erupted at the seminary that was held in fall, 1975, in Snowmass, Colorado, some four hours west of Boulder. Trungpa presided, but neither Ginsberg nor Waldman was present. The poet W.S. Merwin, interested in expanding his Buddhist training, and his then-partner the poet Dana Naone attended the seminary.

On Halloween, a party was given to celebrate the end of the second and the

beginning of the intense third and final stage of the seminary. Merwin and Naone attended but did not stay. Summoned by Trungpa, they refused to return, and were confronted in their apartment by other seminary students who, acting for Trungpa, met their resistance by assaulting them and abducting them to the party, where, against their wills, they were stripped naked at Trungpa’s order, and humiliated.

These facts are not in dispute. This shocking event circulated through published

writings in the aftermath and in Buddhist communities, and has reverberated in

the record of Beat poetry and poetics. – Editors at Journal of Beat Studies

Let’s begin.

Chapter 7

L’ affaire Merwin quickly became a hot gossip item on the coast-to-coast literary scene.

Its first effect was to create a wave of poetry-politics backlash against the Kerouac School. Robert Bly, who’d already been quietly criticizing Ginsberg for inviting only his friends to teach poetry at Naropa, now opened fire, discussing the “Merwin episode” (whose facts he had a very fuzzy idea of) in public at every opportunity.

Ginsberg, fearing the loss of a $4000 grant to the Kerouac School from the National Endowment for the Arts, responded by initiating the “Merwin cover-up” (later known as “Buddha-gate”). He contacted both Bly and Merwin and asked them to inform the NEA that there was no connection between Trungpa’s alleged misbehavior and Naropa or the Kerouac School.

Chapter 8

At the summer, 1978 session of the Kerouac School, the Merwin episode was constantly under discussion. Few, if any, of the poets on the summer faculty had seen the class report, but all had an opinion. Robert Duncan, for instance, compared the stripped lovers, Merwin and Dana, with Adam and Eve, expelled from the Garden. (Which made Trungpa into — God?)

Toward the end of that summer there appeared in the Rocky Mountain News a very interesting story about Naropa. Tibetan Brings Buddhism to Boulder, the headline announced. Inside the story, a scene at a Trungpa lecture was described. A student asked a question about why classes already paid for are constantly being interrupted by requests from the administration for more money. Trungpa dismissed the question by telling the student to be patient, then, snapping his fingers for a glass of water, continued to speak, telling his listeners they were “nothings,” that their lives were like “flat Coca-Cola — full of yukiness, and yukiness has no personality.”

The original Don Siegel picture had long seemed a perfect allegory to fit the Trungpa story. In mid-December, the new version of The Invasion of The Body Snatchers hit the screen of the Village Theatre in Boulder.

By New Years, “pod,” a new generic term for the local Buddhists, was sweeping through the non-Buddhist segment of Boulder’s population. “Do the pods know what we’re up to?” we asked around Boulder Monthly. “What are the pods going to do next?”

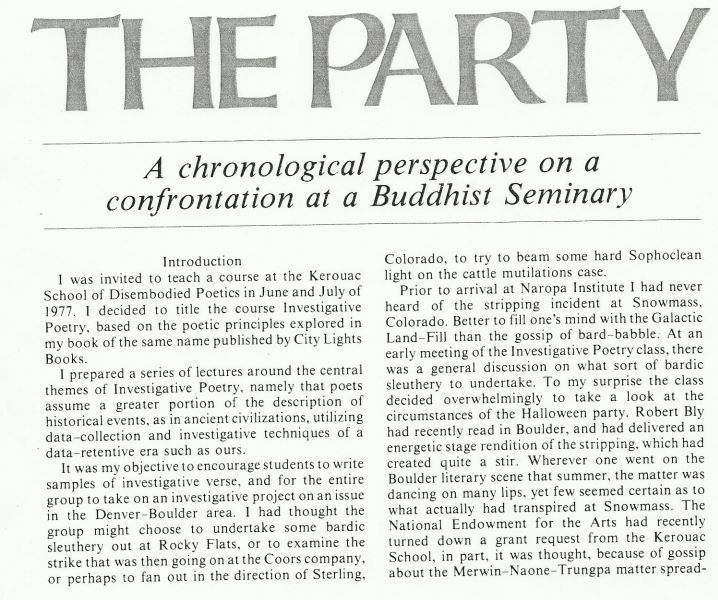

‘The Party’ PDF Link below

Chapter 10

Why was the publication of The Party kept a secret until the last minute?

There was the consideration of possible sabotage. Some of the pods we at the magazine had encountered had been very intense people, when it came to defending the dharma. Rumor had it that one follower of Trungpa, a man we knew, had recently performed a scalping. Such characters might be capable of anything.

Further, we feared that Allen Ginsberg would find some way to interfere with or prevent the publication. “Watch out for Allen,” Ed Sanders had warned us from the beginning. “He’ll do anything he can to keep this thing from coming out.”

Chapter 11

Two days after the magazine came out, Ed Sanders flew in from California. His arrival and one-night stay were kept a close secret. At least one physical threat against Sanders had been received, and this came from a male pod with an unstable history and a record of violence. Sanders was understandably apprehensive about being in Boulder at all, and slipped out of town in the morning, clutching a brown paper shopping bag full of Boulder Monthlys and looking both ways as he climbed into his ride to the airport.

At my house, the phone kept ringing. We’d pick it up, and no one was at the other end. Made us nervous, yes, but nothing ever happened.

Chapter 12

At Boulder Monthly, we started to lose ad accounts from local Buddhist businesses, like the Boulder Bookstore, biggest in town. One Naropa faculty member wrote in to accuse us of a “blatant smear.” On the other hand, many, many people with axes to grind against Trungpa and the Buddhists began to beat a path to our offices, eager to spill their stories to anyone who would listen.

On March 19, the Naropa poets held a big reading at the University. “Where are Tom Clark and Ed Dorn?” somebody in the audience called out. “Home watching television,” sneered Michael Brownstein.

I was asked by the Berkeley Barb to report on the recent Buddhist/poetry doings in Boulder. To my subsequent piece of reportage on the “Buddha-Gate” affair I attached the signature “Robert Woods,” which became my byline in the Barb.

The following is an excerpt from:

The Urgency of Community: The Suturing of Poetic Ideology During the Early Years of the

Loft and the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics

A DISSERTATION

SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA

BY

Rebecca Weaver

***

A great deal of writing about the original incident that involved Trungpa, W.S. Merwin, and Dana Naone (and the subsequent events) appeared in literary reviews, popular interest magazines, reports, and letters, during the five years immediately following the incident, but no one performed a scholarly study of what the events meant to poetry, even though they were collectively called “poetry wars.” After the 1980 publication of Tom Clark’s The Great Naropa Poetry Wars, which collected some reports, interviews, and letters,

there was a precipitous drop-off in writing about the events until the late 1990s, a fact I discuss later. While the Beats and those connected to them have received increased critical attention over the last decade, the amount of poetry scholarship on the Beats or those they influenced (such as Anne Waldman) is still relatively small, and to my knowledge, there is no scholarly study that treats the Great Naropa Poetry Wars as a problem of poetry. There is

one that treats Trungpa’s behavior during the Merwin / Naone Incident (as well as other incidents) as a problem of theology.

3

This chapter reviews the literature about the event from that time period and is the only scholarly treatment of the Great Naropa Poetry Wars.

In what follows, I describe the original incident and read the written reactions to it as documents of poetry and community.

In the fall of 1975, the poet W.S. Merwin and his partner, the Hawaiian poet Dana Naone, traveled to Snowmass, Colorado, to attend Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s Intensive Training Seminar.

In early 1975, Merwin mentioned to Anne Waldman that he was interested in

expanding his Buddhist training, and she suggested that he come to Naropa to investigate its offerings.

He and Dana Naone traveled Boulder that summer, and Merwin informally

participated in some of the activities of the Poetics School. While there, Merwin became acquainted with Trungpa and asked if he and Naone might attend the intensive training seminar to be held in Snowmass that September. The couple had not completed any of the prerequisite trainings, and so at first their request was denied, but Merwin prevailed upon Trungpa, who eventually acquiesced.

As the training progressed through September and October, Merwin and Naone

participated selectively in the training exercises and group activities, specifically in some of the chants used during meditation. These chants contained some violent imagery, and owing to Merwin’s background as a pacifist and peace activist (through which he met and became friends with Allen Ginsberg) he felt that he could not recite those chants. This selective participation created some distance and tension between the couple and some of their fellow seminarians. For Halloween, Trungpa threw a party to celebrate the end of the second stage

of training and the beginning of the intense third and final stage. It was a costume party: come as your neurosis. Merwin and Naone stopped briefly at the party and decided to retire early. Trungpa arrived later and asked after the couple. On discovering that the couple had already left for the evening, he asked students to invite them back down to the party, but the couple declined. Trungpa then ordered the students to bring the poets down from their

room, even if by force. Merwin and Naone locked and barricaded their doors, and the seminary students managed to get in by breaking their glass patio door. Merwin engaged in fisticuffs and broke a bottle to use as a weapon. When he realized that he had drawn blood, he surrendered, and Merwin and Naone were taken to Trungpa.

Trungpa insulted the couple and they argued back. Trungpa tried to get Naone to agree with his argument that because the two of them were Asian, they had access to wisdom that white people did not. She refused and turned the discussion toward war, and Merwin joined in. Trungpa instructed the couple to strip, as he had ordered other revelers to strip previously that evening. Naone and Merwin refused, and he ordered his students to strip them. Merwin and Naone fought the students who attempted to strip them, and Naone asked students to help her. A student stepped in to help, Trungpa attacked him, and

eventually the pair was stripped naked and left standing in the room. After Trungpa stripped himself and ordered everyone else still clothed to disrobe, Merwin and Naone left the party.

A few days later, they met with Trungpa and stayed for the rest of the training (another three weeks), but left before the next big party.

Over the years, many who heard this story have wondered why they stayed after such treatment. In an interview with the Investigative Poetry students, Merwin explained their decision to stay:

(Trungpa) asked us to stay on. I said the decision must be Dana’s, since I thought she had had much the worst of it. He urged her to please stay. Said there would be no more incidents; “one landmark was enough.” We had talked it over, of course, and we did so again, in front of him. We’d come to study the whole course; we’d taken it (as he knew) seriously; we wanted to finish what we’d begun, and not be scared off. The last lap, about to begin, was the famous Tantric teachings. We said that if we stayed, it would be with no guarantees of obedience, trust, or personal devotion to him. He said alright [sic]; so did we, and we shook hands.

They stayed through the end of the training, but left soon after, declining to attend the end of-training bash.

Over the next five years, events related to and written about the Merwin / Naone Incident at Snowmass came to be known as “The Great Naropa Poetry Wars.” They highlighted the frictions evident in the changes in attitudes among poets, in hidden tensions (subsequently laid bare) lurking underneath the amicable relationships of poets who had some investment in the success of the poetics school, in decisions the poets were forced to make because of these rupturing events, and in how these events altered or created persistent perceptions about Naropa and the Poetics School. Some of these perceptions included views of the poets as being in thrall to a religious dictator, poets sacrificing “poetry” to Buddhism, the school putting students and poets in danger, and the school creating a “star system” of poets. Those perceptions did damage in the effects they had on the way the school was run and it damaged relationships among poets otherwise friendly to the community. They caused a shift in goals (aesthetic, poetic, institutional, political) and directions. While poetry might have worked as a suturing symbol for a short time, the

instability created by different definitions of poetry, as well as contradictory pressures placed upon it, was too much for it to stand.

The Great Naropa Poetry Wars

Tom Clark

Published 1980

Tom Clark (1941-2018)

Tom Clark Papers – Washington University in St. Louis

Tom Clark – Allen Ginsberg Project

Why did the Dalai Lama, touring America for the first time, cancel from his itinerary a visit to the acknowledged capital of Tibetan Buddhist religion in America, Boulder, Colorado?

The local lama, Chogyam Trungpa, had extended the invitation through his Vajradhatu organization. A Boulder stop on October 5 appeared in the Dalai Lama’s early tour schedule. Then in mid-tour the schedule was changed without explanation. Extra days in Seattle were added, followed by a direct trip to Ann Arbor, leaving out Boulder.

Would a Frenchman tour Canada and leave out Montreal?

What were the Dalai Lama’s reasons?

The word from the Buddhist community here is that there’s bad blood between the big lamas. Karl Springer, an officer in Chogyam Trungpa’s organization, last year charged the Dalai Lama with conspiring to assassinate the Karmapa, another exiled high lama, originator of Trungpa’s power. Assassination talk is common in the Trungpa camp. The Boulder guru keeps a household protection squad, known as the Vajra Guard. They are the Beefeaters of Buddhism. When the guru goes out in public, so do they. (In between times, they meditate.) The rumor is, they’re armed with M-16’s. Others say it’s submachine guns.

Last year the Karmapa, Trungpa’s old benefactor, started an American organization of his own, which now has a dozen or so local branches, challenging Trungpa’s chain of 50 pay-as-you-go spiritual outlets. Trungpa’s is the most recent Oriental sect to capture the Yankee carriage trade. What he doesn’t need is competition from back home.

This summer, when Trungpa attended a show of Japanese floral arrangement at a university art gallery in Denver, he was attended by six guards.

You never know whose hitmen are liable to be hiding out in the Ikebana.

Tenzin Gyatso, the Dalai Lama, is in his early 40’s, as is Trungpa. He’s got a nice life provided by his followers in India and Switzerland.

No wonder the Dalai Lama is steering clear of the Rockies. Trungpa’s army carries guns that shoot poems. To a Tibetan paraphysician, those are more dangerous than bullets.

As recently as 1960, the year after a mass exodus from Tibet of that country’s religious moguls — including the Dalai Lama and Vajracarya the Venerable Chogyam Trungpa —there were still 2,400 Buddhist monasteries and 106,000 practicing clergy in the Chinese-occupied mountain kingdom. Today only ten monasteries remain physically intact and open to the faithful. The total of Buddhist priests has dwindled to about 2000.

Under Chinese rule, the religious life of Tibet has been severely diminished but by no means extinguished. A recent visitor to one of Lhasa’s remaining monasteries, reporting in the Manchester Guardian, told of flocks of pilgrims and penitents —many of them in modern Chinese-style proletarian clothing — flinging themselves to the ground in deep prostrations, mumbling fervent prayers, kissing the hands of statues, rubbing their faces in the cloth drapes behind holy images, and gluing offerings of coins and cash to the walls with gobs of yak butter.

The people of this remote, mysterious, and primitive land still take their religion seriously, despite two decades of active attempts by the Chinese colonial government to discourage, if not extirpate it.

Literacy in both Tibetan and Chinese languages is on the rise in Tibet. Public health standards, which previously did not exist, are im proving rapidly. The population is increasing. There is now a guest house in Lhasa for foreign tourists. And there is even that trademark of the contemporary, inflation: a shared single room in the guest house will set you back $136.

The Chinese have shown an interest in improving living conditions in Tibet. The Tibetan people, however, seem to prefer their old religion to their new living conditions, if we can believe reports like the one in the Guardian. The Chinese governors would be glad to oblige them, except for one thing: : religion in Tibet is very closely related to politics.

This year the Chinese made the news wires by saying come on home to the Dalai Lama, his 20,000 followers in India, and the rest of the 85,000 religious refugees who fled Tibet in 1959.

“We welcome them and will receive them cordially,” Peking says.

“Nice words are not sufficient,” replies the Dalai Lama, and leaves for a summer vacation in Switzerland, where he has 1200 followers, to be followed by a fall tour of the U.S., where he now has several times that many.

Who wants to leave a nice quiet contemplative life in Switzerland or America to take a chance on getting thrown off a Himalaya by a bunch of goons from the Red Guard?

The Chinese Parliament recently approved new laws guaranteeing religious freedom in Tibet.

“Let’s wait and see,” says the Dalai Lama from his Alp, as he plans his coast-to-coast U.S. itinerary.

The Chinese are inviting the monks back, but nobody’s promising them a return to the days when they got to make up the laws, act as the national police force, and run the country. Still-fresh memories of life during the Chinese invasion in the fifties have convinced Tibet’s emigre clergy to stay put in exile for the time being.

Remnants of their spiritualistic hegemony over the homeland drew the eye of Alain Jacob, the Guardian’s Peking correspondent. Visiting the Lhasa Museum, he saw “dried and tanned children’s skins, various amputated human limbs, either dried or preserved and numerous instruments of torture that were in use until a few decades ago …”

These were the souvenirs and instruments of the vanished lamas, proof, Jacob notes, that under the Buddhist religious rule in Tibet “there survived into the middle of the 20th-century feudal practices which, while serving a well-established purpose, were nonetheless chillingly cruel.”

The “well-established purpose”? Maintaining social order in a church-state.

Old habits die hard. The dream of a harmonious religious kingdom under the rule of a stern but compassionate guru-monarch survives in Tibetan Buddhism to this day —but not in Lhasa. Nor elsewhere in Tibet. The kingdom is something in the minds of the exiled clergy, who are working in the “outside world” — for in their hearts none of them can ever really leave the homeland—to obtain it. Of them, the Chinese unconvincingly claim to know nothing. Even the Tibetan tour guide Alain Jacob met in Lhasa professed to be “unable to say whether any of the spiritual leaders of Tibet had ever gone to a country other than China.” Jacob points out the guide was Chinese-trained. Peking doesn’t wish to publicly acknowledge what its recent behavior so clearly shows: the exiled religious government, as long as it thrives in exile, remains a threat to Chinese rule in Tibet.

2.

In 1938 the supreme abbot of Surmang, a district of Eastern Tibet, sat down one day, said “This is the end of action,” closed his eyes and went into Samadhi, the standard yogic trance that signals the death of a Tibetan holy man.

The abbot was the tenth Trungpa Tulku – tenth reincarnation of the Trungpas, an 800-year-old succession in the Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism.

The monks of Surmang badly needed a new abbot, so they sent somebody to see the head man of the Kagyu school in Lhasa, the sixteenth Gwalya Karmapa.

“Where can we look for the eleventh reincarnation of Trungpa, Holiness, and we mean quick?”

“I’ll work on it,” said the sixteenth Karmapa. “Gimme two, three weeks.”

Before long it came to the sixteenth Karmapa in a vision that the monks could find the eleventh Trungpa by traveling five days north from their monastery to a certain village where in a south-facing hut there dwelt a farmer with a red dog and a year-old son . . . the sixteenth Karmapa supplied every detail but the farmer’s phone number.

The monks made their way to the high plateau country, where, under the 18,000 foot spire of a mountain known as the “home of the king of spirits,” they stepped into a tent made of yak’s hair, which housed a considerable stench, and saw by the light of a smoky yakbutter lamp the diminutive eleventh Trungpa, who as he relates in his autobiography, waved his little hand and gave them a smile as wide as a Hammond organ.

A month later, the young eleventh Trungpa was taken in a formal procession to the Surmang monastery and deposited on the “lion throne,” a gold chair with white lions carved on the sides. In front of him was placed a table piled up with his formal seals of office. Sitting in a monk’s lap, the eleventh Trungpa received robes and gifts and homages from incarnate lamas, heads of monasteries and simple monks of the district. At the climax of the ceremony, the sixteenth Karmapa gave the baby a ceremonial haircut, the first snip-snips of which caused a sudden thunderstorm, followed by a brilliant rainbow, regarded without dispute among the gathered lamas as an auspicious sign.

At the age of five American kids are in kindergarten. At five, the young Trungpa had already been separated from his parents and from all children of his own age; had learned to think of himself as part of his country’s spiritual royalty; and was receiving training from the monks in reading and writing, the recitation of the Tibetan alphabet and mantras.

The monks saw to it that the young supreme abbot stayed too busy to remember it’s lonely at the top. After a hard night of Buddhist scripture study, however, the eleventh Trungpa dreamed restlessly of airplanes, trucks and cowboy boots.

“Forget that nonsense,” the monks advised when the boy confessed his dreams.

One day when the young Trungpa was prostrating himself, some Chinese soldiers marched past the monastery. The boy was eleven years old.

It was 1950. The Dalai Lama was for a time allowed by the invading Chinese Communists to stay on his throne in Lhasa. The monasteries remained largely untouched. But native resistance grew over the years, especially in the Kham Territory of Eastern Tibet, where the Dalai Lama’s loyal swordsmen were being supported by CIA airlifts. The swordsmen were flown out to Colorado, trained in modern warfare, then flown back into Tibet. Their guerilla activity accelerated the conflict, which turned the eleventh Trungpa’s throne into a hot seat by the late 1950’s.

In 1959, the Chinese advanced into Tibet in force. Helped by his CIA-trained guards as well as by actual CIA case officers, the Dalai Lama slipped away from his palace in Lhasa and out of the country.

The eleventh Trungpa, now twenty, survived an arduous trek across the Himalayas into India. On the way, finding himself stranded briefly by seasonal floods, he spent several days playing around with plans for a millenial kingdom called “Shambhala,” whose ruler would liberate mankind from the Dark Age. This imaginary kingdom is of some importance in the eleventh Trungpa’s story, since it later came to be a corporate reality in the United States —under the names Vajradhatu, Nalanda, Naropa.

3.

In India the eleventh Trungpa received political asylum from the government, personal greetings from Nehru and Radhakrishnan, and a job from the Dalai Lama —as spiritual adviser to the Home School for young lamas in exile.

Perhaps even more important than any of these other gifts and homages, however, was the English language tutoring he received in India. It prepared him for Oxford, where he matriculated on a Spalding scholarship in 1963.

(In his autobiography, Trungpa credits his English teacher, a welfare worker, and the Tibet Society of the United Kingdom for procuring the scholarship. Al Santoli, a later student of Trungpa and currently a researcher of things Tibetan, suggests that the CIA may have had a hand in getting the eleventh Trungpa into Oxford. The CIA, however, has declined to release to Mr. Santoli any files their Tibetan office may hold on Trungpa, and Trungpa himself does not communicate with journalists, so this is a difficult point to clarify.)

In the thin, pure mountain air of his home, the eleventh Trungpa had lived the discreet, ascetic life that befits a young abbot. At Oxford, he encountered a different life. Young English gentlemen of his age were not discouraged from tasting alcohol. In his Buddhist robes, women found the eleventh Trungpa appetizingly exotic. He also discovered Western art, literature and philosophy— inhaling a whole culture in gulps.

But you can’t learn your way into a millenial kingdom.

With Akong Tulku, a monk of his own age who’d helped him escape from Tibet, Trungpa now founded the Samye-Ling Meditation Center at a former English Buddhist retreat house in Scotland. Among the disciples who consulted him at Samye-Ling were several artists and writers, including the American poet Robert Bly, who made the pilgrimage in 1971.

The eleventh Trungpa was now called Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche. “Rinpoche” is Tibetan for “precious one” —a title given to lamas, abbots and kings.

He published his autobiography, Born In Tibet, in an English translation. With the help of Bly and others, he prepared a series of lectures for publication under the title Meditation In Action.

In 1968, Trungpa returned to the East. The high point of his trip was the ten days he spent on retreat as a guest of the royal family of Bhutan. On retreat, he determined to expose the materialism of the modern world. At the age of 29, the materialism of the modern world can seem like a problem, especially if you’re being comfortably put up by royal families all over the globe.

Returning to the British Isles, the eleventh Trungpa became the first Tibetan ever to receive British citizenship, which he maintains to this day.

But even as a British citizen and resident of Scotland, Trungpa continued to find the spreading of the Dharma in the West to be slow going. The materialism of the modern world proved as infectious as it was condemnable. Trungpa speaks in his autobiography of a period of “ambivalence,” and then of “blacking out” at the wheel of a car —had he been drinking? —and of the car smashing through the window of a joke shop, leaving his left side partially paralyzed.

After the accident—“it was a message that I wasn’t serious enough about what I was doing,” he said years later —the eleventh Trungpa renounced his monastic vows and married an aristocratic and virginal 16-year-old Englishwoman who had been one of his students.

The marriage provoked the displeasure of Trungpa’s longtime friend and colleague, Akong Tulku. Akong opined that for a guru to drop his pose of inscrutability and mystery would be a serious lapse in “con-manship.” How can you ever make Occidentals serve you properly, Akong asked, if you are overly familiar with them?

Faced with an internal revolt at Samye-Ling, led by Akong, the eleventh Trungpa consulted the I Ching, which told him to cross the big water. America had been bothering the eleventh Trungpa’s dreams for years. With his wife, he now fulfilled an eighth-century Buddhist prophecy which said that when the metal bird flew in the sky, the teachings would be carried over the Western Ocean.

4.

It was March 1970, when Trungpa and his bride stepped off the metal bird in Canada. They spent the next six weeks obtaining U.S. visas, and finally entered this country in May.

In the mountains of Northern Vermont, an advance contingent of Trungpa’s students had taken over a 500-acre farm, which they now called Tail of the Tiger. There Trungpa quickly established the first Tibetan Meditation Center on this continent. Tail of the Tiger was incorporated as a non-profit, tax-exempt church where disciples of Trungpa could meditate, study and reside.

The town clerk of the nearest village, Barnet, estimated the value of the farm and land at $350,000. Trungpa explained that the purchase price had been raised through dues and donations from the members of his church.

The construction of new buildings at Tail of the Tiger—the name was later changed to Karme-Choling—took six years. The Meditation Center was built almost entirely by students, one of whom estimates that a million dollars in labor costs were saved by avoiding outside contractors. Over $600,000 was spent on construction materials. That money was raised from dues, donations, and loans from students. (The practice of borrowing money from students has gone on to become a traditon in Trungpa’s educational system.) Once the extent and seriousness of the project had been demonstrated, loans were also obtained from local banks.

The Center was completed in time for the December, 1976 visit to the U.S. of the sixteenth Gwalya Karmapa — the man who’d conjured the eleventh Trungpa out of a yak-hair tent and into the lion throne of Surmang.

(In keeping with Trungpa’s sense of the occasion, Karmapa was received as visiting royalty, with the maximum pomp and circumstance. He pulled up at Karme-Choling at the head of a caravan of snowmobiles containing his retinue of a dozen red-robed monks, plus personal appurtanances that included 50 singing canaries. A red carpet longer than several end-to-end football fields was unrolled to keep “His Holiness'” feet from touching the snow. Prostrate disciples lined both sides of the red carpet as the visiting holy man made his way to the Center, where he was regaled with a banquet fit for a king, in a setting of poinsettas and birds of paradise. Later, Karmapa continued on to Boulder, where the town’s most impressive mansion was rented to provide him with a rest stop.)

But Trungpa’s first set of students at Tail of the Tiger possessed neither the discipline of Tibet nor the decorum of Oxford, both of which he expected of them.

“You look silly,” Trungpa told one student. “Get a haircut.”

The student obediently did so; he also put on a suit. Today he is an executive director of Trungpa’s Naropa Institute, where the administration always sports neat suits and fresh haircuts.

The brand of philosophy Trungpa dispensed at Tail of the Tiger and elsewhere was a weird blend of aristocratic decorum, monastic stringency and personal eccentricity. “Crazy wisdom” was a tradition in the Trungpa line. Depending on the time of day, it could include anything but the kitchen sink.

Trungpa soon established a name for himself on the East Coast. The poet Anne Waldman made a pilgrimage from New York to meet him in the fall of 1970. (The same week, she had been planning a trip to Cuba which fell through for financial reasons —though Waldman later admitted she has “often thought Trungpa jinxed it.”) Waldman told the guru she was exhausted by her work at the St. Marks Poetry Project. Should she give it all up?

“New York City is a holy city,” Trungpa told her. “Go back to New York City and be a warrior.”

Waldman, later to become an important soldier in Trungpa’s American poetry army, has never forgotten the concept of spiritual warfare to which the Tibetan master introduced her in 1970. “What I like about the situation (at Naropa Institute),” she told an interviewer years later, “is everybody coming here specifically to be a warrior.”

The idea of ongoing universal metaphysical combat is as ingrained in Trungpa’s version of Tantric Buddhism as it was in Milton’s vision of warring angels in Paradise Lost. It found early expression in his American teachings. His lectures of 1971-1973 overflow with images of battle, swords, crushing, cutting, decapitating . . . uneasy symbolism, indeed, but apparently not totally unattractive to Trungpa’s American disciples.

“In the Vajrayana (Tantric Buddhism),” he told them in one lecture, “war is regarded as an occupation. You need to learn from a master warrior.” The crazy-wisdom guru, Trungpa explained, is like a “wild doctor or surgeon” — the Great Warrior, whose function is to hack your ego into little pieces. “We do not want to trust a wild doctor or surgeon,” Trungpa pointed out. “But we must.”

“Cutting through” became a Trungpa touchstone. “Cutting through spiritual materialism” was his working slogan. He ridiculed his students to their faces: the wild doctor has to cut through all attachments.

In a culture where a very popular song by The Crystals once carried the message “He hit me … it felt like a kiss,” it isn’t totally surprising that religious students should take to the image of the wild doctor who “cuts you into pieces” and “throws darts at you.” If Trungpa’s description doesn’t exactly make you want to bump into the crazywisdom guru on a dark night, then maybe you’ve got a lot of squeamishness to “cut through.”

“Trungpa is like a doctor,” Anne Waldman said in 1977. “The situation in this country is so sick, so neurotic-materialistic, spiritually materialistic, general insanity —things are so out of hand that he is coming into a situation that needs doctoring.”

Trungpa’s crazy-wisdom doctor is at least a spiritual cousin of Dr. Benway, the apocalyptic junkie surgeon of William S. Burroughs. Dr. Benway enters the operating room raving and flings his scalpel into the patient from 15 paces.

In 1966, in the Massachusetts Supreme Court, poet Allen Ginsberg testified that Naked Lunch, the book in which Dr. Benway made his American debut, was not obscene. The book, said Ginsberg, was a serious work, treating the serious national problem of multiple addictions — “addiction to materialistic goods and properties . . . and most of all, an addiction to power or addiction to controlling other people by having power over them . . . throughout the book there are dramatic illustrations of people whose obsession or lust is for control over the minds and hearts and souls of other people.”

Naked Lunch, said its creator, “treats a health problem.”

Chogyam Trungpa, the wild doctor of Buddhism, was treating a national spiritual health problem in his new country. How else could you found a Shambhala Kingdom in a nation of neurotic materialists?

With a few drinks ot sake under his belt, the gentle, playful “Rinpoche” became Dr. Benway.

“When in the mood to crack the whip,” an ex-disciple later recalled, “the prince does so with heavy-lidded wrath, taking a minimum of shit, his retainers looking on with sneering awe. I remember a night in Vermont. It got ugly.”

Trungpa did not take up permanent residence in Vermont. Instead, like an important lama making the rounds of his spiritual wards, he traveled quite a bit—to Berkeley, where Shambhala Publications was bringing out his books, to Boulder, where his students were part of a considerable local religious ferment, and anywhere else the Buddhist free-dinner circuit took him.

On his first visit to Boulder in 1970, the nearby mountains stirred in the eleventh Trungpa’s memory treasured scenes of his native land. He soon rented a house in the mountains, then later several buildings in town, including one that had housed the former Satchidananda Yoga Institute. In 1971, he established a formal meditation center, Karma Dzong, in a large older building downtown. Three floors of the building were eventually put to administrative use, with the fourth reserved for sitting meditation.

Working out of this building, a new corporate organization called Vajradhatu controlled a rapidly growing coast-to-coast network of “dharma centers,” or Dharmadhatu. (There are now 50 such centers in American cities.)

Trungpa purchased 360 acres of land west of Fort Collins, to found the Rocky Mountain Dharma Center. He also bought land in Southern Colorado and in half a dozen other states. The Shambhala Kingdom, with landholdings approaching $1 million in value, was growing like Topsy.

During a 1971 visit to the Tassajara Zen retreat center south of San Francisco, Trungpa established an informal alliance with Suzuki-roshi, the West Coast’s most respected Zen master. After Suzuki-roshi’s death in December, 1971, many of his followers abandoned Zen practice and joined Trungpa.

Trungpa’s avowed intention at the time was to establish not only a Tibetan Buddhist church but a Tibetan Buddhist culture in America. To this end, he held a conference on Tibetan dance in Boulder in 1973. Out of this developed the Mudra Theatre Group. Concurrently, the Maitri therapy project was formed, based on a 90-acre farm outside New York City.

In 1973 Trungpa inaugurated his Vajradhatu seminary, an annual 3-month intensive retreat for selected advanced students. Seminaries since 1973 have taken place at resort centers of Tibetan-type beauty all across the northern part of the continent —from Lake Louise to Snowmass to Land O’ Lakes.

The first seminary was held in the shadow of the Grand Tetons at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Among the eighty students Trungpa guided through the “three yanas” (hinayana, mahayana, vajrayana) was the famous poet Allen Ginsberg, already a meditation student of the master.

By 1974, the eleventh Trungpa was one of the most prosperous of America’s new religious leaders, with followers numbering in the thousands. The only major component missing from his American organization was a school of arts, letters and religious studies—an institute that would not only educate but draw national attention and respect—and even, why not, financial support—to his burgeoning kingdom.

The Book

The Great Naropa Poetry Wars

Tom Clark

Bits and Pieces

Chapter 5.

Naropa Institute, founded in Boulder in 1974, became that component.

The Institute was formed by Chogyam Trungpa as a non-profit educational institution, subsidiary to the Nalanda Foundation, a “secular wing” of Vajradhatu. While legally distinct, Naropa and Vajradhatu maintained common officers and boards of directors.

Trungpa’s directors and officers included several men with excellent minds for law and business. The careful division of Trungpa’s holdings into separate corporate entities served at least two important purposes. Tax money could be saved, and the reputation of Naropa as a civilian institution could be protected by “the water-tight compartment argument” —an appeal to the original corporate legal divisions.

Chapter 6.

From almost the beginning of the seminary, Merwin’s presence created a problem. A pacifist, he first of all refused to participate in the prescribed chanting of poems addressed to horrific deities. So did Dana Naone.

I later asked Allen Ginsberg to describe these poems. He read several aloud. They had lines like “as night falls you cut the aorta of the per-verter of the teachings,” and “you enjoy drinking the hot blood of the ego.” An RX straight out of the prescription book of Dr. Benway!

“The poems are very un-American to say the least,” Ginsberg didn’t have to explain to me. “From the point of view of somebody who hasn’t been a poet, they’re really off the wall.”