ORIGIN OF THOUGHT AND LANGUAGE

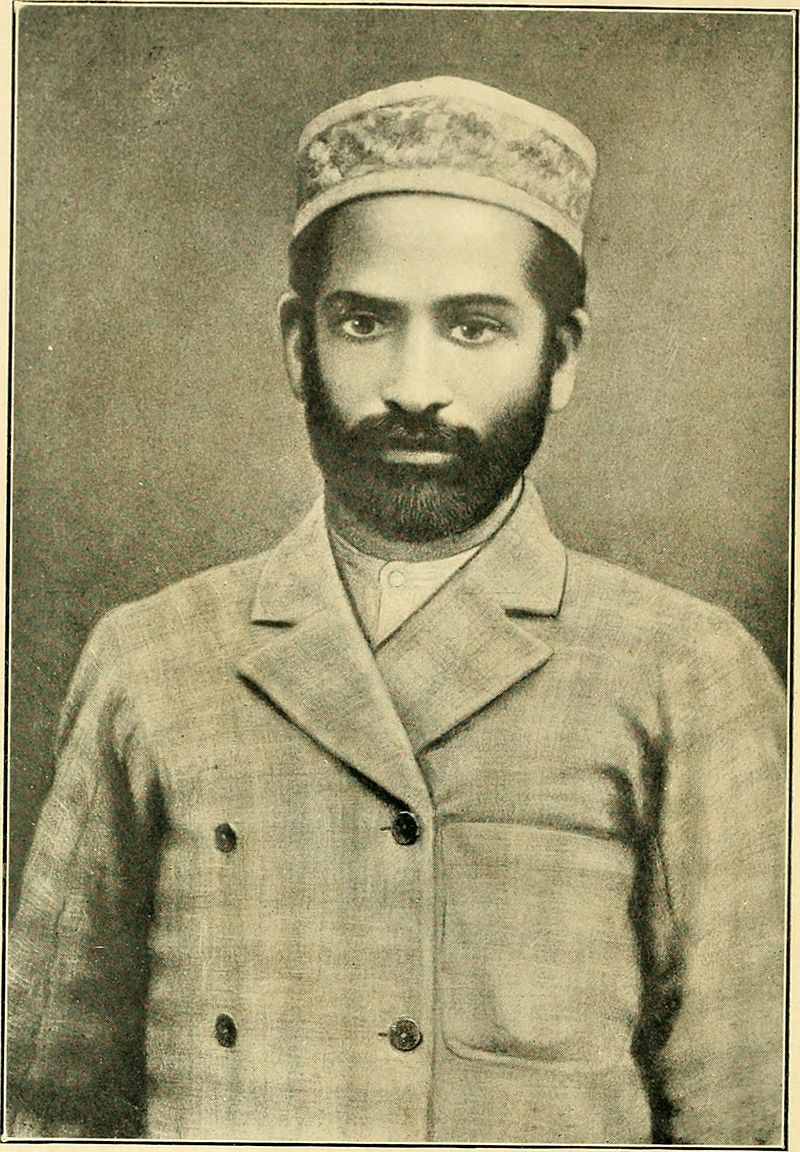

“The Vedas are the oldest books of the world (and) they are coeval with the advent of man”*

Pandit Guru Datta Vidyarthi, Letter to Lala Jivan Das, 1884

t is necessary to say something about the origin of language, which presupposes almost simultaneously with it the origin of thought. Language, as Aristotle calls it, is but the outward thought, and thought is the inward language. Both of them are logos. Wherever a word exists in any language, the corresponding thought is sure to exist, and a thought has no clear and distinct shape in the mind of the thinker, unless it is fixed in a word. So the thought and language of man grew simultaneously, and our surest method of tracing the thought of man to its very root is to trace the history of human speech. Herein lies the greatest importance of the Vedas. They supply us with ample material for tracing the history of human speech and thought to its very origin. And inasmuch as they give us this when and how of the origin of all human thought; they have a right to be called the revelation. No other existing book can satisfy this condition, and can, therefore, be no revelation. But where then did language come from? This theory of revelation will lead us in the right direction.

t is necessary to say something about the origin of language, which presupposes almost simultaneously with it the origin of thought. Language, as Aristotle calls it, is but the outward thought, and thought is the inward language. Both of them are logos. Wherever a word exists in any language, the corresponding thought is sure to exist, and a thought has no clear and distinct shape in the mind of the thinker, unless it is fixed in a word. So the thought and language of man grew simultaneously, and our surest method of tracing the thought of man to its very root is to trace the history of human speech. Herein lies the greatest importance of the Vedas. They supply us with ample material for tracing the history of human speech and thought to its very origin. And inasmuch as they give us this when and how of the origin of all human thought; they have a right to be called the revelation. No other existing book can satisfy this condition, and can, therefore, be no revelation. But where then did language come from? This theory of revelation will lead us in the right direction.

It is well known that the Indian grammarians call the alphabetical sounds of the Sanskrit language the akshara Samanmoya (Akshara अक्षर akṣara). This means the Veda, i.e., the revelation which consists of literal sounds. In other words according to the Hindu theories of revelation, which we have seen to be the only true one, these literal sounds are (318R) the eternal sounds of nature. The origin of the articulate speech of man which is made of these literal sounds is in the sounds of nature. And this every body will acknowledge if he examines carefully the roots of the Sanskrit language, out of which have been formed, as Yaska and Shakatayana tell us, all the nouns and verbs, &c., of the language. The roots are the sounds which man learned to imitate from nature, and out of these by-and-by grew the language which is now our pride, as also did its sister languages. For sometime men used to talk only with roots, as they could not have done otherwise. And these roots expressed single ideas. When man had progressed so far that the combination of two single thoughts became a necessity of his life, two roots expressing the two different ideas were placed side by side. For better understanding, I give an illustration from a later process in the formation of language, the composition of nouns and from the English language, which will be more familiar to the reader. The word kingdom means the house or dominion of a king. Before their composition, both of these words conveyed a separate and independent idea. When the necessity was felt of expressing an idea compounded of these two, these words were placed side by side. But dom did not as yet lose its independence, and carried to the mind of the speaker, as before, the idea of a separate power. By and by, however, it became dependent on king, and lost its separate and independent power. In fact it became to borrow an expressive idea from the Chinese grammarian empty. Hence forward it was only a mere suffix, and nothing more.

Having thus far explained the process of the formation of nouns I may leave the rest, for here I shall only have to do with nouns. One thing let us remember now. It is that in order to understand any thought properly, we must trace the word which is its outward representative to its root, and thence form the radical meaning to trace all the intermediate steps to the then meaning of the word. Then only shall we find what were the sensuous beginning of all our ideas, i.e., their true revelation. But we must have light-houses to guide our courses in this dark ocean of linguistic investigation. There must be some intermediate link that may give us some clue at least to the origin and development. And that light house, that link, is supplied by the Veda. There we see the ideas growing and coming out, and in asmuch they are the only existing revelation.

THE NAMES OF THE VEDA EXPLAINED

Revelation in Sanskrit is called either the Shruti, the Amnaya, or Sumamnaya, and the Veda. I have explained the meaning of Shruti. It means the voice of nature. When these voices have done their work, man has come to know something, to possess all those ideas which he could not have possessed without them;

And indeed it is only by a thorough and critical examination of the Samhitas that we can reach in that mass of song to revelation true. This Veda is quite independent of the Samhitas. It will exist all the same, whether they exist or not. But if the Samhitas be lost, it will become difficult for us to recover the true Veda; for it is to be found in them alone, as their names themselves testify. The Samhitas are called respectively the Rig Veda, the Yajur Veda, &c. The meanings of these are the following: — The Rig Veda means a book, a collection in which the Veda is found in the Richas or praises; the Sama Veda means that in which the Veda is on the Samans or chanting hymns; and so on. With this meaning these books are in a figurative sense, sometimes simply, spoken of as the Vedas; but their true names are simply the Rik, the Saman &c., or, the Rig Veda, the Sama Veda, &c.

Thus we see that in reality the Veda cannot be a book, it cannot even be articulate speech. The true Veda is rather a matter of feeling and knowing. And that feeling and that knowledge the Samhitas give us in a very tangible form.

More on Guru Datta

https://beezone.com/?s=guru+datta

Beezone Note:

The statement “Samhitas be lost, it will become difficult for us to recover the true Veda” reflects a deep concern about the preservation and continuity of Vedic knowledge.

Background:

-

Samhitas: These are collections of hymns, mantras, and chants that form the foundational texts of the Vedic tradition. Each of the four Vedas (Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda) includes a Samhita, which is its core and most ancient layer.

-

True Veda: The term suggests the essence or the unadulterated, original form of Vedic wisdom as it was intended by the seers who composed or received it. This ‘true Veda’ encompasses not only the textual content but also the spiritual and cultural context in which it was used and transmitted.

-

Loss and Recovery: The concern expressed here is that if the Samhitas were to be lost or corrupted, it would pose a significant challenge to rediscover or reconstruct the Vedic tradition in its pure form. This is because the Vedas were primarily transmitted orally for centuries before being written down, relying heavily on meticulous recitation techniques to preserve their exact sound, meaning, and structure.

Contextual Elaboration:

-

Oral Tradition and Its Challenges: The Vedic Samhitas were passed down through generations via an oral tradition known as Shruti (what is heard). The preservation depended on rigorous memorization and precise recitation. Losing this oral chain could result in distortions or gaps in the knowledge.

-

Spiritual and Cultural Significance: The Vedas are not just texts but are seen as the embodiment of divine knowledge in the Hindu tradition. They guide rituals, philosophy, and spirituality. A loss of the Samhitas could mean losing touch with the spiritual heritage they represent.

-

Modern Implications: In the modern era, the preservation of ancient texts has transitioned to written formats and digital media. However, the true essence of the Vedas, which includes the correct pronunciation and intonation critical for their ritualistic and spiritual efficacy, might still be at risk without the continuity of oral traditions.

This concern underscores the importance of safeguarding not just the content of the Vedas but also the traditions and practices that keep their spirit and efficacy alive.

*The claim that the Vedas are the oldest books in the world is a widely held belief, particularly in Hindu traditions, and is often attributed to their antiquity and oral preservation. While definitive historical evidence is challenging due to the Vedas’ oral tradition and the lack of precise dating methods for ancient texts, there are references and scholarly arguments that support this view:

Points Supporting the Claim:

-

Antiquity of the Vedic Tradition:

- The Rigveda, considered the oldest of the four Vedas, is believed to have been composed between 1500 BCE and 1200 BCE, based on linguistic and archaeological evidence. Some Indian scholars propose even earlier dates, sometimes as far back as 3000 BCE or more.

- The oral tradition of the Vedas predates their written form, which adds to their claim as among the earliest works of human thought.

-

Oral Tradition and Preservation:

- The Vedas are unique in that they were transmitted orally for centuries with precise phonetic accuracy using elaborate memorization techniques (e.g., padapatha and krama-patha). This oral tradition is regarded as one of the longest continuous literary traditions.

-

Comparisons with Other Ancient Texts:

- While other ancient texts, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh (circa 2100 BCE), Egyptian Pyramid Texts (circa 2400 BCE), and Sumerian tablets, are older in written form, they lack the comprehensive philosophical, ritual, and poetic scope of the Vedas.

- The Vedas are not merely literary works but represent a comprehensive worldview, including hymns, rituals, and philosophical teachings, which many consider unparalleled in antiquity and influence.

-

Scholarly References:

- Scholars like Max Müller, an Indologist, acknowledged the Rigveda as one of the most ancient religious texts known to humanity.

- In A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature (1860), Müller writes about the Rigveda’s antiquity and its central place in understanding early human civilization.

-

Cultural and Historical Continuity:

- The Vedas remain foundational to Hindu culture and philosophy, influencing later texts like the Upanishads, epics (Mahabharata and Ramayana), and classical Indian philosophy. This continuity underscores their early origin and enduring significance.

Counterpoints:

It’s important to note that while the Vedas are among the oldest religious texts, terms like “oldest books” depend on definitions. For example:

- The Vedas were initially oral and only written down centuries later, while some other texts, like the Egyptian Pyramid Texts, were written down earlier.