SOCRATES: … Among the ancient gods of Naucratis in Egypt there was one to whom the bird called the ibis is sacred. The name of that divinity was Theuth, and it was he who first discovered number and calculation, geometry and astronomy, as well as the games of checkers and dice, and, above all else, writing.

Now the king of all Egypt at that time was Thamus, who lived in the great city in the upper region that the Greeks call Egyptian Thebes … . Theuth came to exhibit his arts to him and urged him to disseminate them to all the Egyptians. Thamus asked him about the usefulness of each art, and while Theuth was explaining it, Thamus praised him for whatever he thought was right in his explanations and criticized him for whatever he thought was wrong.

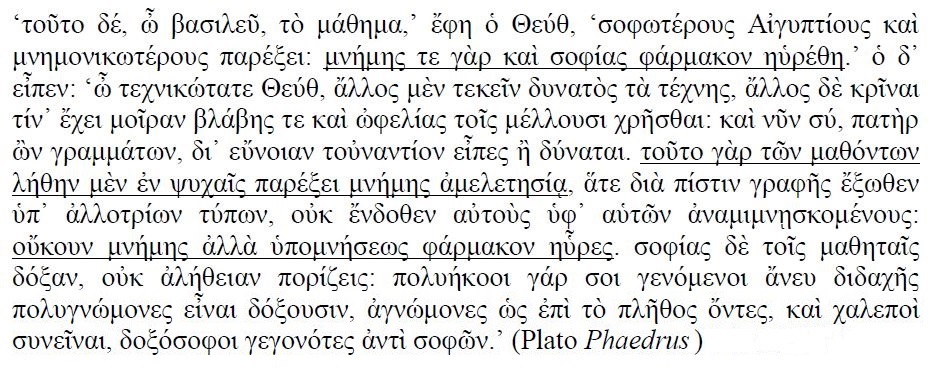

The story goes that Thamus said much to Theuth, both for and against each art, which it would take too long to repeat. But when they came to writing, Theuth said: “O King, here is something that, once learned, will make the Egyptians wiser and will improve their memory; I have discovered a potion for memory and for wisdom.” Thamus, however, replied: “O most expert Theuth, one man can give birth to the elements of an art, but only another can judge how they can benefit or harm those who will use them. And now, since you are the father of writing, your affection for it has made you describe its effects as the opposite of what they really are. In fact, it will introduce forgetfulness into the soul of those who learn it: they will not practice using their memory because they will put their trust in writing, which is external and depends on signs that belong to others, instead of trying to remember from the inside, completely on their own. You have not discovered a potion for remembering, but for reminding; you provide your students with the appearance of wisdom, not with its reality. Your invention will enable them to hear many things without being properly taught, and they will imagine that they have come to know much while for the most part they will know nothing. And they will be difficult to get along with, since they will merely appear to be wise instead of really being so.”

PHAEDRUS: Socrates, you’re very good at making up stories from Egypt or wherever else you want!

SOCRATES: But, my friend, the priests of the temple of Zeus at Dodona say that the first prophecies were the words of an oak. Everyone who lived at that time, not being as wise as you young ones are today, found it rewarding enough in their simplicity to listen to an oak or even a stone, so long as it was telling the truth, while it seems to make a difference to you, Phaedrus, who is speaking and where he comes from. Why, though, don’t you just consider whether what he says is right or wrong?

PHAEDRUS: I deserved that, Socrates. And I agree that the Theban king was correct about writing.

SOCRATES: Well, then, those who think they can leave written instructions for an art, as well as those who accept them, thinking that writing can yield results that are clear or certain, must be quite naive and truly ignorant of [Thamos’] prophetic judgment: otherwise, how could they possibly think that words that have been written down can do more than remind those who already know what the writing is about?

PHAEDRUS: Quite right.

SOCRATES: You know, Phaedrus, writing shares a strange feature with painting. The offsprings of painting stand there as if they are alive, but if anyone asks them anything, they remain most solemnly silent. The same is true of written words. You’d think they were speaking as if they had some understanding, but if you question anything that has been said because you want to learn more, it continues to signify just that very same thing forever. When it has once been written down, every discourse roams about everywhere, reaching indiscriminately those with understanding no less than those who have no business with it, and it doesn’t know to whom it should speak and to whom it should not. And when it is faulted and attacked unfairly, it always needs its father’s support; alone, it can neither defend itself nor come to its own support.

PHAEDRUS: You are absolutely right about that, too.

SOCRATES: Now tell me, can we discern another kind of discourse, a legitimate brother of this one? Can we say how it comes about, and how it is by nature better and more capable?

PHAEDRUS: Which one is that? How do you think it comes about?

SOCRATES: It is a discourse that is written down, with knowledge, in the soul of the listener; it can defend itself, and it knows for whom it should speak and for whom it should remain silent.

Plato. c.399-347 BCE. “

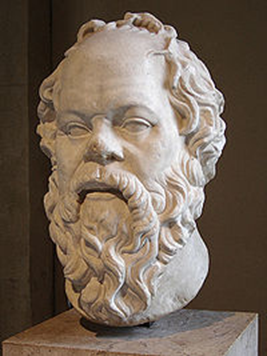

Socrates on the Forgetfulness that Comes with Writing

Socrates (469-399 BCE) was a Greek Philosopher who thought and taught through argumentative dialogue, or dialectic. Socrates did not write down any of his thoughts, however his dialogues were recorded by his student and protégé, the philosopher Plato (428 – 347 BCE). Here Socrates discusses the deficiencies of writing.

SOCRATES: … Among the ancient gods of Naucratis in Egypt there was one to whom the bird called the ibis is sacred. The name of that divinity was Theuth, and it was he who first discovered number and calculation, geometry and astronomy, as well as the games of checkers and dice, and, above all else, writing. Read more >>>