Essay by Jonathan Ott

Ecstasy! The mind harks back to the origin of that word. For the Greeks ekstasis meant the flight of the soul from the body. Can you find a better word than that to describe the bemushroomed state? In common parlance, among the many who have not experienced ecstasy, ecstasy is fun, and I am frequently asked why I do not reach for mushrooms every night. But ecstasy is not fun. Your very soul is seized and shaken until it tingles. After all, who will choose to feel undiluted awe, or to float through that door yonder into the Divine Presence?

R. Gordon Wasson, The Hallucinogenic Fungi of Mexico

R Gordon Wasson first tasted ecstasy late on the night of June 29, 1955, high in the mountains of Oaxaca, near the Mazatec village of Huautla de Jimenez, in the Sierra Madre Oriental of southern Mexico. Wasson and his photographer Allan Richardson were that night introduced to the hallucinogenic mushrooms of Mexico by the Mazatec shaman Maria Sabina. To the tune of the thaumaturge’s chanting, singing, and percussive clapping in the stillness of the night, Wasson and Richardson knew a soul-shattering experience under the influence of the divine inebriant Pszlocybe caerulescens. To the best of our knowledge, they were the first outsiders ever initiated into the Mexican sacred mushroom cult (81).

Wasson rescued the last vestiges of the cult from imminent extinction in the few remote parts of Mexico where it survived into the twentieth century, and today the renown of the mushrooms has spread far and wide. From the epicenter in Huautla, the shock waves of Wasson’s discovery spread throughout the world, provoking widespread recreational use of numerous species of mushrooms chemically related to the Mexican sacred fungi (21,22,54,83). This remarkable resurgence of interest in an ancient sacrament has shown no signs of abating, and I expect that our modern ‘magic mushroom’ cult will continue to grow in coming years.

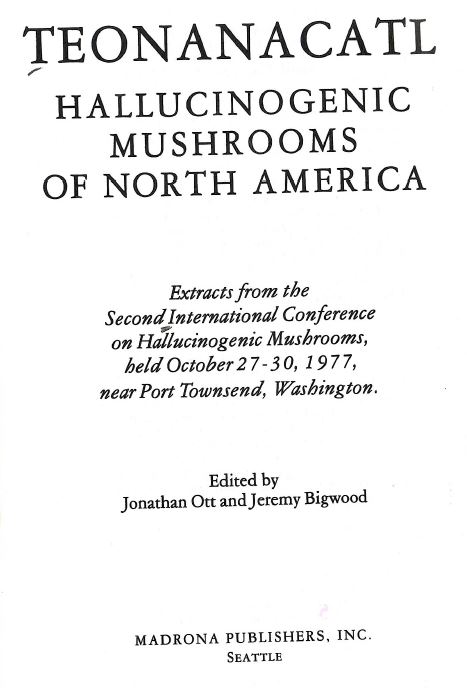

TEONANACATL: HALLUCINOGENIC MUSHROOMS OF NORTH AMERICA

In this introduction, I will trace the history of the Mexican hallucinogenic mushrooms. An examination of the archaeological record will establish the antiquity of the cult, while a chronicle of the modern studies of the mushrooms will detail their introduction to the modern world. I hope this information will enhance the reader’s understanding of the current legal and medical status of the hallucinogenic mushrooms of Mexico.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD

Among the oldest archaeological artifacts of Meso-America are a group of carved stone icons in the form of mushrooms, usually with human or animal figures emerging from the ‘stipe’ of the mushroom. Some 200 of these icons have been discovered in Guatemala, El Salvador, and southern Mexico (4,5,27,37). The oldest of the ‘mushroom stones’ have been dated at about 1500 B. C., and Valentina and Gordon Wasson have suggested that they were emblematic of the ancient mushroom cult in the Maya area (27,68,81).

Mushroom motifs also abound in the Tepantitla frescos of the great Meso-American metropolis Teotihuacan. These murals are believed to have been executed sometime in the middle of the first millennium A.D. The most striking of these murals depicts the Toltec rain god, Tlaloc, from whose upturned palms water emanates. Beneath the falling raindrops, we find a number of mushrooms. These are juxtaposed with the figures of priests attending the deity, suggesting that they represent our sacred mushrooms. Beneath Tlaloc is a picture of Tlalocan, the watery paradise or Elysian fields ofToltec mythology, and again we see the mushrooms growing where men disport themselves with mythic butterflies ( 2 7, 81).

The sacred mushrooms appear in several of the few surviving pictographic books of pre-Columbian Meso-America (27,81). These beautifully painted scrolls, called amoxtli by the Aztecs, were accessible only to the priests, and detailed the history and rituals of the peoples who painted them. The mushrooms figure most prominently in the Mixtec Codex Vindobonensis, painted early in the sixteenth century. One entire panel of this codex is devoted to the mushrooms (6,25).

These and other precious artifacts place the mushroom cult at least as far back as 3500 years ago. They show that the cult held sway from the Valley of Mexico (site of the modern capital) through Central America, and they testify to the importance of the mushrooms in the spiritual life of the Meso-American· Indians of pre-Columbian times.

THE CONQUEST AND INQUISITION

The Spaniards, under Cortes, conquered Mexico, or the Aztec Empire, in 1521 (56). A number of sixteenth century writers referred to the use of the mushrooms in various parts of Mexico (27,81). An educated Indian, Tezoz6moc, writing in Spanish in 1598, described the ingestion of inebriating mushrooms in celebration of the coronation of Moctezuma II in 1502. Moctezuma II, the last emperor of the Aztecs, ruled until he was imprisoned by Cortes in 1519 (56). From the writings of Sahagun, a friar, and Hernandez, a botanist, we learn that the mushrooms were called teonandcatl, ‘sacred mushrooms,’ or, more precisely, ‘wondrous mushrooms.’ We learn that there were several species, that these were bitter and often taken with honey and cacahuatl (a stimulating decoction of cacao beans, chile, and other spices) (27,81).

By and large, the accounts of the Spaniards were superficial and condescending, and the mushrooms were repeatedly vilified as an idolatry. ‘God’s flesh’ became ‘Devil’s flesh’ in the minds of the sixteenth century clerics (27, 78,81). The Indian communion with teonanacatl was unfavorably compared to the Holy Communion of Catholicism. As friar Motolinia expressed it late in the sixteenth century: ”They called these mushrooms teonandcatl in their language, which means ‘flesh of God,’ or of the Devil that they worshipped, and in this manner, with this bitter food they received their cruel god in communion. ” In the seventeenth century the mushrooms were denounced as an idolatry by the Office of the Inquisition, and a horrendous autoda-fe was celebrated (36, 78).

There is no indication that any of the Spaniards ingested the mushrooms or attempted to study their use (70,81). Perhaps their reluctance was motivated by fear of the iron arm of the Inquisition. Somtime before 1629, Hernando Ruiz de Alarcon wrote, in the language of the Aztecs, the terms the shaman used to invoke his God. His was no disinterested study-the information was extracted under duress from the terrified Indians (36, 78) .. The Spaniards ruthlessly forced apostasy on the hapless Indians, and by the advent of the twentieth century succeeded in eliminating the use of the mushrooms in all but a few remote mountainous zones (25,27,81). With the passing centuries, the bigotry of Ruiz de Alarcon and the accounts of the sixteenth century friars were forgotten. The vision-producing mushrooms were unknown to modern science, with the exception of a few scattered reports in medical literature of accidental intoxications.

THE PHARMACOTHEON IS RECOVERED FROM OBLIVION

In 1915, the American ethnobotanist W. E. Safford advanced the daring hypothesis that the hallucinogenic mushrooms had never existed, that the Spaniards had mistaken peyotl (peyote buttons, dried tops of Lophophora williamstii) for mushrooms, or were deliberately misled in this regard by the Indians (59). Because of his prestige, Safford’s theory won wide acceptance, and many readers first learned of the mushrooms from his paper, only to be told that they never existed (61,70). Safford’s error, combined with the overwhelming forces of’ acculturation,’ would have interred forever the memory of the mushrooms had it not been for the indefatigable work of Dr. Blas Pablo Reko, a pioneering ethnobotanist in Mexico. Reko declared that he did not accept Safford’s thesis, and began to search for the remains of the ancient cult in the mountains of Oaxaca ( 61, 70).

Reko’s work attracted Richard Evans Schultes, then a young graduate student at Harvard University. Schultes had worked on the ethnobotany of peyote in Mexico, and so was familiar with Safford’s theory regarding the mushrooms. In 1938, Schultes and Reko traveled to Huautla de Jimenez, and obtained the first identifiable botanical specimens of teonandcatl. *

*Schultes discusses the botanical identification of teonanacatl in Pan I-A.

These were deposited in the Farlow Her barium at Harvard ( 61), and were ultimately shown to represent three different species (70). Two years earlier, Robert J. Weitlaner had become the first outsider to handle the mushrooms, but his specimens, also sent to Farlow Herbarium, arrived in unidentifiable condition (70). In 1939, Weitlaner’s daughter Irmgard and her future husband, a young anthropologist, Jean Bassett Johnson, became the first outsiders to attend a velada (literally a ‘night vigil,’ the Spanish word used by the Mazatec Indians to describe a mushroom ceremony) (34). The Johnsons’ ve!ada took place in Huautla. Although they observed the use of the mushrooms, they did not partake of them. Reko sent dried mushroom material to C. G. Santesson for chemical study. He observed a ‘half narcosis’ in frogs and mice following administration of extracts of the mushrooms but this intrjguing lead was not pursued (60).

Despite this promising start in the late thirties, the Second Worl? War delayed the rediscovery of the mushrooms. Johnson was killed m combat m North Africa, and Schultes was diverted to South America. Santesson died in 1939, and Reko applied himself to other studies until his death in 1953. The mushroom cult again fell by the wayside and began to lapse into oblivion. This was the situation in 1952, when the American ethno mycologists Valentina and Gordon Wasson first learned of the Mexican mushroom cult. The Wassons had by that time been studying the cultural role of mushrooms ‘ethnomycology’ for over 25 years. Their studies of the field they named ‘ethonomycology’ had led them to surmise that our primitive ancestors worshipped mushrooms. They knew not which mushrooms nor why they were worshipped, but they had been led to their conclusion by the peculiar connotations of mushroom names in Europe, and the diametrically opposed attitudes toward fungi that these names conveyed. The Wassons learned that all Eurasian peoples were emotional about mushrooms, either loving them or hating them, so they devised the words ‘mycophilia’ and ‘mycophobia’ to describe these contrasting attitudes (68, 76, 79,81).

After a thorough review of the sixteenth century accounts of the mushroom cult, and a study of the fieldwork of Reko, Schultes, and Johnson, the Wassons, with the assistance of Robert W eitlaner, made their first expedition to Mexico in the summer of 1953. That year and the following summer, the Wassons were able to learn tantalizing bits of information about the mushrooms, and to obtain a few precious samples. Persistence paid off and on June 29, 1955, Gordon Wasson was able to collect a large quantity of Pstlocybe caerulescens and was that same day introduced to Maria Sabina, who agreed to perform a ve!ada for him that night. Sensing that he was on the brink of a great discovery, Wasson hoped Maria would offer him a dose of the mushrooms. He was delighted when that night in the home of Cayetano Garcia, he was served chocolate, for he remembered that Sahagun had written that the mushrooms were taken with cacahuatl. Maria Sabina, solemn, dignified, reverently incensed the mushrooms Wasson had collected earlier that day, and offered him and his photographer six pairs each. She ingested 13 pairs. The hallucinatory effects of the mushrooms were a revelation to Wasson, explaining the enigmatic phenomena of mycophilia and mycophobia (51,81). Valentina Wasson, a physician, also ingested the mushrooms. Later, she reported her reactions in This Week magazine (80).

The Wassons teamed up with the prominent French mycologist Roger Heim, who accompanied them to Mexico in 1956. Heim returned to Paris with specimens and cultures of the Mexican sacred mushrooms. Heim was able to identify 14 species of divinatory mushrooms, 12 of which were new to science. He was able to grow many of these species in his laboratory in Paris (27). Heim sent cultured specimens of Psilocybe mexicana to the world-famous discoverer of LSD, Albert Hofmann of the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Sandoz. Self-experimentation by Hofmann and his assistants determined that the psychoactive effects were caused by two unique indole alkaloids, designated psilocybin and psilocin, which were expeditiously synthesized (27,28,30,62).* Heim, Wasson, and Hofmann summarized their research in Les Champignons Hallucinogenes du Mexique (27), the most complete and authoritative interdisciplinary study of any drug plant every published. Later research has expanded our knowledge of the distribution and use of hallucinogenic mushrooms in Meso-America (10,13-19,31,38,41,50,58, 63).

TEONANACATL IS RENDERED AVAILABLE TO THE WORLD

In the May 13, 1957 issue of Life magazine, R. Gordon Wasson revealed the discovery of the sacred mushroom cult of Mexico. His article, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” depicted several species of hallucinogenic mushrooms, and described _the modern cult and its history (75). The title, chosen by the editors of Life, caught the popular fancy, and psilocybian fungi were known thenceforth as ‘magic mushrooms.’ Wasson timed the publication of his article to coincide with the release of Mushrooms, Russia and History, which he coauthored with his wife Valentina. ( 81). This magnificent two-volume limited edition of 512 copies detailed 30 years of study of the field the Wassons named ‘ethnomycology.’ Starting with an arduous study of European mushroom names, the Wassons’ astonishing odyssey had led them to the rediscovery of the sacred mushrooms of Mexico. In this remarkable book, they presented their initial observations on the modern cult of teonandcatl, and included a thorough review of its history. With precision and perspicacity, in moving language, Gordon Wasson reverently described the effects of the mushrooms and the significance of his discovery. As befits a great book, Mushrooms, Russia and History became an instant classic, and has sold for up to $1750 at auction.

The Wassons had found the last dying remains of a once mighty cult. In only a few remote areas of Mexico did the mushrooms continue to hold sway over the Indians. In every case where ritual use of the mushrooms was encountered, the beliefs surrounding the cult were mingled inextricably with Christian concepts. The mushrooms were personified as Jesus, and rites were celebrated before crude wooden altars bearing icons representing the baptism in Jordan and Santo Nino de Atocha (a Catholic conception of the youngJesus) (27,53, 78,81).

Soon after the publication of the Life article, outsiders, in search of the mushroom experience, began to make the pilgrimage to Huautla de Jimenez. Maria Sabina became the high priestess of a modern mushroom cult born, like the Phoenix, from the ashes of its predecessor (11,48). In Huautla and other villages, the mushrooms were profaned, reduced merely to articles of the tourist trade. Postcards depicting mushrooms, clothes embroidered with mushroom motifs, and the mushrooms themselves were widely and conspicuously sold (46,47). The transformation of the mushrooms to articles of commerce virtually destroyed the remains of the ancient cult. Self-styled shamans staged spurious mushroom ceremonies for the benefit of the tourists. Maria Sabina herself pronounced a fitting epitaph to the secret cult she had divulged to the world: “Before Wasson, I felt that the mushrooms exalted me. Now I no longer feel this….From the moment the strangers arrived…the mushroom lost their purity. They lost their power, they decomposed. From that moment on they no longer worked.” (11)

A young psychologist named Timothy Leary learned of Wasson’s discovery and journeyed to Mexico to ingest the mushrooms. In 1960, he had his first psychedelic experience with the mushrooms in Cuernavaca (35). Like Wasson, Leary found the effects of the mushrooms to be a revelation, and he eagerly began his own investigations. Leary obtained a supply of synthetic psilocybin from Sandoz Laboratories, and began. his now infamous experiments at Harvard which led to his dismissal from the faculty amid a storm of controversy. Leary then began working with LSD, and the rest of his story_ need not concern us here. In 1968, Leary published High Pnest, a chronicle of his experiences with hallucinogenic drugs ( 3 5). One chapter concerned his experience of the mushrooms in Cuernavaca, and contained marginalia excerpted from Wasson’s startling paper “The Hallucinogenic Fungi of Mexico” (68). Leary’s book was instrumental in introducing the mushrooms to the American public, especially to users of LSD and other hallucinogenic drugs.

Public consciousness of psilocybian mushrooms was further expanded by the publication in 1968 of The Teachings of Don Juan by Carlos Castaneda (7). Castaneda described his apprenticeship to an aging Mexican sorcerer,Juan Matus, who allegedly smoked dried specimens of Psilocybe mexicana. Castaneda’s book became a bestseller, and surely contributed to the growth of the cult of psychedelic mycophagy, despite the fact that he presented no information on the identification of the mushrooms. Wasson eagerly entered into correspondence with Castaneda and even met him twice. In spite of Wasson’s prompting, Castaneda was unwilling ( or unable) to procure specimens of the mushrooms for reliable identification (77). Moreover, certain disconcerting inconsistencies in Castaneda’s accounts defy credibility, and it has even been suggested that Castaneda invented Don Juan, drawing liberally from Mushrooms, Russia and History for his ideas (8,49, 71, 72).

While the books of Castaneda and Leary served to inform the American public (most of whom had not heard of the Wassons or their monumental book) of the existence of hallucinogenic mushrooms in Mexico, they provided no practical information on obtaining or using the mushrooms. In the early sixties, chemical studies showed that many United States species of Psilocybe and Panaeolus produced psilocybin -and/ or psilocin, and were therefore hallucinogenic ( 1, 2, 20, 21,4 3, 5 7 ,64, 66). Chemical, mycological, and ethnological work elsewhere in the world showed that hallucinogenic mushrooms were cosmopolitan ( 3, 25 ,26, 32, 3 3 ,43 ,44, 50, 52 ,65, 7 4, 84). As veterans of the mushroom pilgrimage to Huautla learned that hallucinogenic mushrooms grew in their homelands, the modern cult of psychedelic mycophagy spread far and wide. Australia became an early center of the cult, as did the Indonesian island of Bali (54).

With the advent of the seventies, ‘field guides’ to American hallucinogenic mushrooms began to appear. The first of these was Leonard Enos’ A Key to the Amenican Psilocybin Mushroom, which described 15 species and was illustrated with useless watercolor drawings (9). Though regarded by some to be a pioneering work, Enos’ book in reality was a shoddy fraud. It is obvious that the author never saw the bulk of the mushrooms in his ‘field guide,’ but merely copied the illustrations from line drawings in mycological literature, and colored them according to verbal descriptions in the same literature. Enos also presented a worthless chemical test for psilocybin in mushrooms, and a ridiculous appendix describing some pseudo-religious phenomenon called ‘Subud’ which had nothing to do with mushrooms and was added to flesh out his meager pamphlet.

Numerous mushroom ‘field guides’ that follow Enos’ formula have been published over the years, and continue to appear at an alarming rate. While the information in the pamphlets has not changed much since 1970, at least the current imitators of Enos present actual photographs of the mushrooms, which are usually properly identified (12,23,24,40,42).

Because of the abundance and diversity of indigenous psychotropic mushrooms, the Pacific Northwest has become the modern center of psychedelic mycophagy in the United States (21,22, 83). A number of species are used in the Northwest, notably Psilocybe cyanescens, P. semilanceata, P. pelliculosa, and P. stuntzii, a new species discovered in the course of my own investigations (21,22,83). *

* See Pan II for descriptions and illustrations of the most important hallucinogenic species of the United States, Mexico, and Canada.

Use of hallucinogenic mushrooms is also common in the Gulf Coast states. Stropharia cubensis, a species collected by Schultes and Reko in Huautla in 1938 (27 ,61), and later observed in use by Wasson (81), is the mushroom widely used in Texas, Florida, Alabama, and Louisiana, where it commonly grows (46,54). There are incipient signs of psychedelic mycophagy in the northeastern United States.

In 1976, Jeremy Bigwood and his collaborators published Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower’s Guide, a book that detailed and illustrated effective techniques for growing S. cubensis, one of the species first grown by Heim in Paris( 45) and now proven to be the most easily cultivated psilocybin mushroom. Recently, a number of less distinguished cultivation guides have followed on the heels of the Bigwood book (24,55). Technology for simple home cultivation of hallucinogenic mushrooms has allowed the practice of psychedelic mycophagy to spread to areas of the United States where the mushrooms do not naturally

In the last two years, mushroom ‘truck farms’ have been established in various parts of the country to supply the black market with hallucinogenic mushrooms. In addition, numerous pro

fiteers have begun to offer viable (if unsterile) spores of cubensis to would-be growers via national magazine advertisements. It is indeed unfortunate that these entrepreneurs have exacted exorbitant rates for spores and paraphernalia. (Composted fecal matter, worth only a few cents per pound, has been magically transmogrified to ‘mushroom compost,’ and has sold for as much as $10.00 per pound!).

LEGAL AND MEDICAL STATUS OF PSYCHEDELIC MYCOPHAGY

Even before most Americans had heard of psilocybian mushrooms, they came within the compass of our overzealous legislators, who classified psilocybin and psilocin as controlled substances. Public Law 91-513, the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Contol Act of 1970, made unauthorized possession, sale, or use of psilocybin and psilocybian mushrooms a crime punishable by fine or imprisonment. This ill-conceived action has in no way served to deter use of the mushrooms as recreational drugs, and there is every indication that many more people would begin to use them if given the chance.

I can see no medical justification for proscribing psilocybin. Animal studies have shown this compound to be remarkably non-toxic (29), and I know o{ no case where an adult has been made seriously ill by psilocybian mushrooms. (Children may show a particular reaction to psilocybin with life-threatening symptoms, and a child in Oregon died in 1960 following accidental ingestion of Psilocybe baeocystis (39). It should go without saying that children should not be given the mushrooms or any other psychoactive drug.) Tens of thousands of intentional inebriations occur each year with psilocybian mushrooms in the Pacific Northwest alone, yet no conspicuous medical problems have emerged. Even if the mushrooms were demonstrably dangerous, legal sanctions would not necessarily be warranted. Deadly poisonous mushrooms of the genera Galerina and Amanita, which have killed numerous people in the United States, are controlled by no legal strictures whatever.

Our ill-advised laws against psilocybin have immeasureably hindered medical experimentation with a drug some researchers believe to be the most effective aid to psychotherapy yet discovered. Their good intentions notwithstanding, our lawmakers would do well to examine the writings of Wasson; then they might appreciate the significance of his discoveries, and learn something of the possibilities of the mushrooms. The history of teonandcatl gives us a glimpse of the veneration in which our ancestors held the sacred mushrooms, and, surely, the modern use of the mushrooms is a phenomenon worthy of careful and systematic study. Wasson wrote:

As man emerged from his brutish past, thousands of years ago, there was a stage in the evolution of his awareness when the discovery of a mushroom with miraculous properties was a revelation to him, a veritable detonator to his soul, arousing in him sentiments of awe and reverence, and gentleness and love, co the highest pitch of which mankind is capable, all those sentiments and virtues that mankind has ever since regarded as the highest attribute of his kind. It made him see what this perishing mortal eye cannot see. What today is resolved into a mere drug, a tryptamine or lysergic acid derivative, was for him a prodigious miracle, inspiring in him poetry and philosophy and religion. Perhaps with all our modern knowledge we do not need the divine mushrooms any more. Or do we need them more than ever? Some are shocked that the key even to religion might be reduced to a mere drug. On the other hand, the drug is as mysterious as it ever was.

Maria Sabina was doubtless correct when she said that the influx of strangers to her remote Mazatec hills caused the sacred mushrooms to lose their mystical power ( 11). Although there may today be more communicants with the ‘magic mushrooms’ than ever before, it is a profane and puerile, largely hedonistic cult which has succeeded its venerable ancestor. Wasson has rightly observed that the superficial use of the mushrooms by ignorant thrill-seekers is a desecration (51). Today’s mushroom eater is likely to ingest a mild sub-threshold dose of the mushrooms, often in a social setting, in combination with alcohol and other drugs. Truly, it can be said that he knows nothing of the meaning and potential of the miraculous fungal drug which held his remote ancestors in thrall. The mushrooms deserve better, and we might hope for a resurgence in their use as sacraments. After all, the wise user of teonandcatl may, to paraphrase Blake, hold infinity in the palm of his hand, hold eternity in an hour. He may experience ecstasy, like his predecessors the ancient shamans of Mexico, even know, for a time, the awe, terror, fascination, and mystery of communion with the Gods.

Olympia, Washington

Christmas Day, 1977