Originally published in

The Laughing Man, 1986

“BEAT THE DHARMA DRUM”

THE TRADITION OF SPIRITUAL DEBATE

by Georg Feuerstein

The words of wisdom are the lost objects of the faithful; he must claim them wherever he finds them.

—The Prophet of Islam

If mankind does not achieve a higher sacred and Transcendental view of self and world and Reality, then there is no alternative to the mad gleefulness of conventional religion and the sorry revolt of angry secular mortals.

—Da Love-Ananda The Transmission of Doubt, p. 451.

INTRODUCTION

Freedom of expression enjoys nearly unparalleled official protection in the democratic West (according to law), yet there are few if any remnants of an ancient tradition wherein matters of high “Dharma” or Spiritual principle are freely and publicly debated. How is it that among all public controversies, this great matter—the Enlightenment of Man—has had no forum to call its own, no participants eager for or equal to the challenge of free and lively debate?

According to Webster’s, to enact a debate is “to discuss a question by considering opposed arguments”. Simple enough. A debate worthy of the name requires the presence of two or more individuals (or groups of individuals) willing to represent differing points of view on the same topic. In politics, sports, business, sex, or any of the common pursuits of the day, one quite readily finds such differences of experience, belief, knowledge, or opinion to be loudly debated. Yet, in the matters of true Spiritual life, renunciation, and God-Realization (rather than pseudoreligious or religio-political issues—such as school prayer or abortion), there remains a hushed silence.

Is it possible that there are no disagreements among the faithful? Beyond the institutional politics of interreligious and church-state conflict, what is the fate of the true “debate tradition”, where the nature of the Divine and the quickest route to God-Realization has always been regarded as the most pressing topic at hand?

That grand tradition, described in the following article, is all but extinct. It has withered in the cultural hegemony of the West and the Spiritless aridity of the institutionalized “great religions”. Precious few genuine practitioners are to be found to engage the Great Matters that occupied the ancient Dharma-bearers.

Today there is but one dominant Church, whose members do not broadly confess or even acknowledge Transcendental Being or Reality or the Divine Person. These religionists generally represent only the “religion” of objectivism, materialism, and political idealism—even when they pay lip-service to higher principles and to the existence of God or Spirit. Holding this mortal ideology of Church and State in place, with its metaphysics of anti-metaphysical positivism, is an entire culture that does not admit of the participatory, psychic dimension of life. As Heart-Master Da Love-Ananda points out:

The ultimate product of Western civilization is technology, scientism, communism, totalitarian political movements, reductionist movements. Western civilization is now infecting the entire world, so these results are becoming part of world history. There really are not two cultures operative. Basically, there is the dominant one of scientific materialism, and it is easily snuffing out and overwhelming the previous and rightly dominant culture of participatory Realization, Spirituality, and truly human culture.

Just as certain cultural movements such as Christianity became dominant in the past by making use of the means of the State, or the means of objective or material power, so also in the present, the culture of scientism, materialism, and objectivism is achieving great power and dominance to the exclusion of the Great Tradition of participatory Realization.1

1. Da Love-Ananda, in an unpublished talk given on January 22,1983

We could hardly be further removed from the cultural milieu described in the following survey of traditional cultures. In the ancient esoteric traditions, where the participatory Spiritual life of meditation and sacramental worship was the foundation of true religion, debates among opposing schools and philosophies had great significance. Training in Dharma, renunciate practice, and argumentation began at an early age, so that even the youngest Brahmacharins could appreciate and later participate in the unique institution of “Dharma combat”.

Because Western Man’s creative energies have been confined largely to the goals and struggles of the gross physical and mental life (the first three stages in Master Da’s sevenstage schema of life), the possibilities represented by the realms of Spirit and yogic mysticism have remained uninspected, and even largely unknown. And Realization of the Transcendental Condition of Consciousness Itself has not even been generally considered as a possibility. In order to truly resuscitate the great tradition of Dharma combat, it is necessary that there be a significant restoration of the culture of participatory Spirituality and Realization, and a renaissance in understanding of the world’s Spiritual legacy.

Da Love-Ananda makes a call to all of us to transcend the provincialism of our childhood training, and to embrace an understanding of the East as well as the West:

In fact we are not truly the inheritors of these provincial religious traditions. At this point in history we are all the inheritors of the Great Tradition, the total tradition, and we should acknowledge this. By acknowledging this Great Tradition, we also cease to be merely secular or pagan, or barbaric even.

Eastern culture, taken as a whole, represents the Great Tradition in its fullness—all the stages of life. Western Man is simply Man uninformed. He is Man denied wisdom. He is Man permitted to develop only the lower features of his existence. Western Man has achieved great political power over the centuries. Now, through the ultimate products ofegoic civilization, Western Man, pagan Man, lower Man, is tending to achieve world domination and eliminate, not merely Eastern Man, but the higher cultural possibilities of Man.

Western Man has been bereft of the higher culture. He has been the lower ego pursuing the ideals of the lower ego, magnifying them culturally, socially, and politically. But in the process wherein Western Man is becoming dominant Man, world Man, the higher possibility and the ultimate orientation of Man as living being is disappearing, being eclipsed, being suppressed.2

As part of The Laughing Man’s continuing effort to bring the Eastern tradition to light (as well as the esoteric features of the Judeo-Christian experience), the following survey by Georg Feuerstein focuses on examples of “Dharma combat” in traditional contexts, where monastic education was responsive to the lively interplay of practitioners and those schooled in the niceties of high Dharma. This article is offered in the hope that the true “debate tradition” may again come alive in the spirit of open dialogue and real self-transcending practice.

2. Ibid.

omething extraordinary occurred in the early centuries of the first millennium before Christ. After countless generations of transmitting cultural mores, values, and knowledge through myth and ritual (which is enacted myth), our ancestors embarked on a new course. A new type of consciousness came to the fore, which permitted a different relationship to the world: Humanity, in the form of a few outstanding geniuses, discovered self-critical thought.

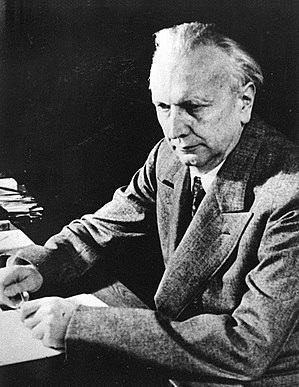

The German philosopher Karl Jaspers rightly spoke of the period between 800 and 500 B.C. as the “axial age”.1

1. See K. Jaspers, The Origin and Goal of History (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1953).

There were Thales, Anaximander, Pythagoras, and then Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle in Greece. And there were Zoroaster in Persia, Lao-tse and Confucius in China, and Mahavira (the founder of Jainism) and Gautama the Buddha in India. They began to ask more searching questions than anyone had dared to ask before, and in many respects they broke with preceding traditions, sentiments, and priorities and formulated new values and lifestyles that, in a complex web of interconnections, were destined to shape the adventure of humanity until modern times.

The “axial age” was marked by the emergence of a new kind of personality, which was more self-defined (or ego-strong) and self-assertive and more capable of sustained clear thinking, but also more selfalienated and doubting. This new type of personality delighted in “independent” (or personal, rather than merely traditional) thought and speech. But, unlike much of today’s professionalized thinking, those early pioneers still developed their thoughts in close discourse with others. Knowledge .held an almost magical fascination for them. It represented both power and danger. And they never missed an opportunity to display and test it in “combat” with their peers.

They began to seriously examine the laws of thought, or logic, and they also studied and showed great ingenuity in formulating principles of logical discourse—the art of discussion or controversy, known as dialectics. Since for most dialecticians the objective was not merely to pursue a logical discussion but also to win the argument, they paid equal attention to the art of public speaking, known as rhetoric.

In Greece it was the Sophists (the “artful teachers”) who drew large crowds whenever they displayed their dialectical skills, more often than not for money. Thinking and arguing were the pastime of well-to-do Greek urbanites, and men like Protagoras, Gorgias, and Hippias catered to their intellectual appetites. They taught the relativity of knowledge and values, and promoted a skeptical or agnostic attitude in regard to metaphysical matters.

Socrates, for whom true knowledge was wisdom, severely censured the Sophists for their pseudo-philosophizing and lack of commitment to a virtuous life. For him rational thought was a means of discovering the Good, though in his dialogues with others we find him as skillful and cunning as any Sophist. His success and charisma were, however, too conspicuous for the establishment, and thus he was executed for treason. But, as is frequently the case with martyrs, Socrates’ fame long survived his tragic death.

The Greek debate tradition was secular in nature, focusing on ethical and political issues. A different situation prevailed in India, where philosophical thinking has always remained within the orbit of religion and spirituality. This is best illustrated in the example of Gautama the Buddha, the Enlightened founder of the ramifying tradition of Buddhism. Gautama was, by any standards, an extraordinary personality. Brought up as a local prince, he was moved to renunciation at an early age. After achieving mastery in two spiritual traditions, he relied on his own native wisdom for guidance in his spiritual search.

At the age of thirty-five, he Realized the State in which there is “neither earth nor water nor fire nor wind”2 and in which all desires are extinguished like the flame of a doused torch. He could have followed the prevailing ideal of living in isolation, “like the single horn of a rhinoceros”. Instead, he chose to turn back to the world—and to communicate the great Truth that he had discovered.

2. Udana VIII.1.

Gautama the Buddha was a culture-creating genius of the first order, and his Teaching was in many respects innovative. It broke with the preceding tradition of belief and mythology. The Buddha advised his disciples not to go by hearsay or the opinion and beliefs of others, but rather to follow their own deepest intuitions after due consideration of the evidence.3 Yet, unlike the Greek Sophists, he did not encourage mere skepticism or relativism.

3. See, e.g., Anguttara Nikaya 1.188.

The “lamp” by whose light he asked his disciples to conduct their lives was not that of the intellect but that of experience and true wisdom, maturing on the basis of rigorous self-inspection, meditative practice, and dispassion. Although he warned of false reliance on reason in spiritual matters, he nevertheless endorsed the use of reason. The rationalism of his Teaching has been found attractive even by modern European minds such as Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Hesse.

The sermons of the Buddha show him not only as an impressive charismatic personality, but also a man capable of penetrating analysis and endowed with extraordinary psychological insight. He possessed the rare gift of “reasoning with the heart”. Many became his disciples after listening to his sermons—undoubtedly a reflection of both his Teaching argument and his personal emanation.

The Buddha’s first disciples were five ascetics with whom he had wandered before he set out on his own quest. When they saw that he was no longer doing penance, they almost refused to even greet him, but were won over by his commanding presence. It was to them that he preached his first sermon, in the Deerpark Isipatana. Then followed many dialogues with other more or less renowned personalities. Among them were Sabhiya (a widely-travelled woman dialectician), Nigrodha (a well-known ascetic who accused the Buddha of hedonism), Upali Gahapati (who came to the Enlightened one to praise his own teacher), King Pukkusati (a skilled debater), and Somadanda (a famous brahmin). They all converted to the Buddha’s Teaching, and became either monks or lay-followers.

The Buddha’s immediate disciples—of whom fifty-nine are reported to have been Enlightened—were also effective disputants. In some cases their effectiveness was not so much due to any great dialectical or rhetorical skills as to their own spiritual radiance. Thus, Vaspa, who made no secret of his ignorance of the subtleties of the Buddha’s Teaching, nevertheless succeeded in converting Shariputra, a well-known debater.

Lacking the greatness and charisma of the born Adept-Teacher, but also needing to vindicate the Teaching in an increasingly complex social environment, the Buddha’s disciples, particularly in later generations, made the verbal and written presentation of his Teaching into an art of communication. They greatly valued in-depth study of the sacred canon, and delved into the intricacies of logic and dialectics. As in Christendom, the custodians and developers of the sacred knowledge were the members of the monastic orders (another of the Buddha’s great innovations).

It was in the monasteries that the Buddhist lore and the secret teachings were passed from master to disciple. It was there that the monks were also trained in rational thinking and argumentation. From the earliest days, they would gather to discuss the Buddha’s Teaching and to test their learning and understanding in dialogue with one another. This led to the “science of debate” (yada vidya) and the “science of logic” (hetu vidya) and the incorporation of all kinds of secular learning into the monastic curriculum. This, in turn, paved the way for later “interreligious” dialogue, the great debates with representatives of traditions other than Buddhism.

While the monastic system did much to preserve and expand the Buddha’s Teaching, it also promoted the kind of arid intellectualism that, in the Christian tradition, goes by the name of scholasticism. The standards of scholarship in the Buddhist monasteries, or viharas, were exacting and high. By the early post-Christian centuries, they had already become influential centers of learning, important repositories of the Buddhist cultural heritage. Apart from the canonical scriptures recognized by their own school, monks and novices were also expected to study the doctrines of rival schools and even nonBuddhist traditions.

One of the greatest of these ancient seats of learning was the monastic university of Nalanda, situated near the modern town of Patna (in Bihar, Central India). It flourished from the middle of the fifth to the end of the eleventh century A.D.

When the Chinese scholar I-tseng visited Nalanda in the seventh century A.D., the monastery harbored more than three thousand monks. Other traditional reports even speak of ten thousand resident scholars, but this is probably an exaggeration. We know, however, that at the philosophical symposium convened by the liberal Emperor

Harsha in the early eighth century, a thousand eminent scholars from Nalanda were present who each could expound twenty collections of Sutras and Shastras. Half that number could expound thirty collections, and possibly ten were qualified to teach fifty collections. Only Shilabhadra, the then Chancellor of Nalanda U niversity, had studied and understood all of them.

It is also recorded that every single day, one hundred pulpits were set up at Nalanda—presumably representing the number of classes held on different topics. Erudition was made into a religious virtue that was richly rewarded by all kinds of honors. However, those who risked themselves in “Dharma combat” and were defeated did not fare too well. According to one source, “The faces of such are promptly daubed with red and white clay, their bodies are covered with dirt, and they are driven out to the wilds or thrown into the ditches.”4 The Chinese traveler Hiuen-Tsang, who visited Nalanda, noted that “Those who cannot discuss questions out of the Tripitaka [the three ‘baskets’, or collections, of the Buddhist Teaching] are little esteemed and are obliged to hide themselves for shame.”5

4. Cited in L. M. Joshi, Studies in the Buddhistic Culture of India (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1977), p. 132.

5. Cited in D. K. Barua, Viharas in Ancient India (Calcutta: Indian Publications, 1969), p. 143.

The atmosphere in the hundreds of monasteries scattered throughout the Indian peninsula was both contemplative and challenging. At Nalanda, and undoubtedly at other similarly renowned temple universities, the competition started at the entrance gate. Applicants were confronted with some hard questions and, we are told, only those demonstrating intelligence and a measure of learning were admitted.

But despite this emphasis on study and erudition, the practical yogic dimension of Buddhism was never altogether neglected. Also, masters like Asanga and Vasubandhu periodically appeared, and their experiential orientation would challenge the scholastic establishment and lead to a revitalization of the primary spiritual aspect of Buddhism.

The great Buddhist masters, of course, always combined in themselves both sanctity and knowledge. Consequently the debates between accomplished adepts was always a dramatic event of historical consequences. One of the best known encounters of this kind is the great controversy between the Indian teacher Kamalashila and the Chinese scholar Hva-san (or Ho-shang), a master of the Ch’an school of Buddhism. The religious debate was a continuation of the Dharma combat fought against Hva-san and his school by Padmasambhava and Shantarakshita in Lhasa, the Tibetan capital. Apparently the outcome of the debate had been inconclusive. Shantarakshita is reported to have left instructions that after his death, should Hva-san’s “heresy” become prominent in Tibet, Shantarakshita’s pupil Kamalashila was to be invited to a formal debate.

The Dharma combat took place at the newly founded Sam-yas monastery in Tibet in the period between A.D. 792 and 794. In the debate Hva-san put his argument first, then Kamalashila responded. The bone of contention was whether Enlightenment was sudden, as the Ch’an school affirmed, or gradual, as was the general viewpoint of Mahayana Buddhism. As can readily be imagined, the encounter was most intense. Kamalashila, spokesman for the gradual approach, emerged triumphant and Hva-san, as was customary, offered the victor’s garland to him. Considering the Ch’an (Japanese Zew) tradition of wen-ta (Japanese mondo), or spontaneous discourse between master and student, the defeat of Hva-san was no mean achievement. Kamalashila’s doctrinal victory was ratified by the king of Tibet, and so Nagarjuna rather than Bodhidharma came to influence the development of Tibetan Buddhism.

At the time of the Buddha, Hinduism (then still Brahmanism) was a chaotic mass of teachers and teachings. Much of what was being taught was simply magical practice, or mythology-laden and heavily ritualistic esotericism. But even within the fold of Hinduism there stirred a new spirit, associated with a more individualistic, rational outlook on life. A testimony to this trend is the Bhagavad Gita, which is an early effort to break away from the world-estranged esotericism of former periods and to formulate a Teaching that could be applied in the midst of an active life rather than only in a remote forest or cave.

The Upanishads, those magnificent creations of Hindu spiritual aspiration, stand, like Gautama the Buddha, at the watershed between the age of mythology and the age of logic. Especially the earlier texts are still filled with mythological stories and imagery. But, significantly, we also find in them the first references to teaching debates. Thus, in the ancient Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (chapter two) is recorded the classic dialogue between the brahmin Gargya and King Ajatashatru. At one point in the debate, Gargya had exhausted his wisdom and fell silent. Ajatashatru asked him: “Is that all?” Gargya replied: “That is all.” Thereupon Ajatashatru exclaimed that Gargya’s wisdom was incomplete and that he did not know the Truth. Gargya humbly replied: “Let me come to you as a pupil.” The king-seer consented, taking him by the hand and leading him away for esoteric instruction.

In the same scripture (chapter three), there is a record of the Teaching contest between the great Sage Yajnavalkya and his challenger Uddalaka Aruni. Uddalaka wanted to test the sage’s wisdom about the Absolute, the brahman, and offered, as was usual in those days, a herd of cows for his stake. At the same time he warned the sage that his head would fall off—we would perhaps say he would “lose face”—if he should fail to answer all his questions convincingly. Yajnavalkya emerged victorious.

Then a woman mystic named Gargi pressed him for answers to her riddle-like questions. Again he proved worthy of his fame, and she acknowledged his victory, saying: “Venerable brahmins, you may think it a great thing if you escape from this man with merely a bow.” One other learned brahmin, Vidagdha Shakalya, questioned the Sage at length. He too was defeated and silenced by the superior wisdom and God-Realization of Yajnavalkya. Then the Sage challenged them to go on questioning him, or else he would start questioning them. Not one of them stirred.

In another story handed down in the same Upanishad (chapter four), we hear of Yajnavalkya’s discourse with King Janaka, who offered thousands of cows to learn the Sage’s secret knowledge. He ended up offering his kingdom and himself at the feet of that great Adept.

Instruction in the esoteric lore did not come cheap. But the brahmin who really knew the Reality behind the teachings about the blissful Ground of the world expected those who had heard and understood not But despite this emphasis on study and erudition, the practical yogic dimension of Buddhism was never altogether neglected. Also, masters like Asanga and Vasubandhu periodically appeared, and their experiential orientation would challenge the scholastic establishment and lead to a revitalization of the primary spiritual aspect of Buddhism.

The great Buddhist masters, of course, always combined in themselves both sanctity and knowledge. Consequently the debates between accomplished adepts was always a dramatic event of historical consequences. One of the best known encounters of this kind is the great controversy between the Indian teacher Kamalashila and the Chinese scholar Hva-san (or Ho-shang), a master of the Ch’an school of Buddhism. The religious debate was a continuation of the Dharma combat fought against Hva-san and his school by Padmasambhava and Shantarakshita in Lhasa, the Tibetan capital. Apparently the outcome of the debate had been inconclusive. Shantarakshita is reported to have left instructions that after his death, should Hva-san’s “heresy” become prominent in Tibet, Shantarakshita’s pupil Kamalashila was to be invited to a formal debate.

The Dharma combat took place at the newly founded Sam-yas monastery in Tibet in the period between A.D. 792 and 794. In the debate Hva-san put his argument first, then Kamalashila responded. The bone of contention was whether Enlightenment was sudden, as the Ch’an school affirmed, or gradual, as was the general viewpoint of Mahayana Buddhism. As can readily be imagined, the encounter was most intense. Kamalashila, spokesman for the gradual approach, emerged triumphant and Hva-san, as was customary, offered the victor’s garland to him. Considering the Ch’an (Japanese Zen) tradition of wen-ta (Japanese mondo), or spontaneous discourse between master and student, the defeat of Hva-san was no mean achievement. Kamalashila’s doctrinal victory was ratified by the king of Tibet, and so Nagarjuna rather than Bodhidharma came to influence the development of Tibetan Buddhism.

At the time of the Buddha, Hinduism (then still Brahmanism) was a chaotic mass of teachers and teachings. Much of what was being taught was simply magical practice, or mythology-laden and heavily ritualistic esotericism. But even within the fold of Hinduism there stirred a new spirit, associated with a more individualistic, rational outlook on life. A testimony to this trend is the Bhagavad Gita, which is an early effort to break away from the world-estranged esotericism of former periods and to formulate a Teaching that could be applied in the midst of an active life rather than only in a remote forest or cave.

The Upanishads, those magnificent creations of Hindu spiritual aspiration, stand, like Gautama the Buddha, at the watershed between the age of mythology and the age of logic. Especially the earlier texts are still filled with mythological stories and imagery. But, significantly, we also find in them the first references to teaching debates. Thus, in the ancient Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (chapter two) is recorded the classic dialogue between the brahmin Gargya and King Ajatashatru. At one point in the debate, Gargya had exhausted his wisdom and fell silent. Ajatashatru asked him: “Is that all?” Gargya replied: “That is all.” Thereupon Ajatashatru exclaimed that Gargya’s wisdom was incomplete and that he did not know the Truth. Gargya humbly replied: “Let me come to you as a pupil.” The king-seer consented, taking him by the hand and leading him away for esoteric instruction.

In the same scripture (chapter three), there is a record of the Teaching contest between the great Sage Yajnavalkya and his challenger Uddalaka Aruni. Uddalaka wanted to test the sage’s wisdom about the Absolute, the brahman, and offered, as was usual in those days, a herd of cows for his stake. At the same time he warned the sage that his head would fall off—we would perhaps say he would “lose face”—if he should fail to answer all his questions convincingly. Yajnavalkya emerged victorious.

Then a woman mystic named Gargi pressed him for answers to her riddle-like questions. Again he proved worthy of his fame, and she acknowledged his victory, saying: “Venerable brahmins, you may think it a great thing if you escape from this man with merely a bow.” One other learned brahmin, Vidagdha Shakalya, questioned the Sage at length. He too was defeated and silenced by the superior wisdom and God-Realization of Yajnavalkya. Then the Sage challenged them to go on questioning him, or else he would start questioning them. Not one of them stirred.

In another story handed down in the same Upanishad (chapter four), we hear of Yajnavalkya’s discourse with King Janaka, who offered thousands of cows to learn the Sage’s secret knowledge. He ended up offering his kingdom and himself at the feet of that great Adept.

Instruction in the esoteric lore did not come cheap. But the brahmin who really knew the Reality behind the teachings about the blissful Ground of the world expected those who had heard and understood not merely to bring cows or gold, but to become his disciples.

In other words, the debaters presupposed each other’s personal integrity: A person was assumed not merely to entertain certain intellectual views but also to live by them. Therefore, to lose an argument meant more to them than it means to us moderns. It was more than a temporary annoyance. It was a complete loss of face and of one’s stance in life. Hence it called for a radical act of reorientation, that is, one’s conversion to the viewpoint and lifestyle of the victor.

Conversion was also the objective of the great debates between different schools within Hinduism, Buddhism, andjainism, but also of the more spectacular interreligious debates, in later times, between Buddhists, Hindus, and Jainas. Hinduism, which lacks an ecclesiastic structure, was never a proselytizing religion, at least not until the time of the missionary efforts of Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda in the nineteenth century. It only developed a meager dialectics under the influence of Buddhism, which, by contrast, had from the beginning an “evangelical” orientation. Although monks did not undergo missionary training, they were expected to learn, like their medieval Christian counterparts, the “liberal arts” of logic, dialectics, and rhetoric. The point of all this learning was, in part at least, to defeat their intellectual opponents in debate.

Often these opponents were supplied from within Buddhism itself. And there was no dearth of such rivals, since Buddhism, like Christianity, is a highly schismatic religious tradition. Thus, over the centuries, the monks of the Hinayana schools would be found arguing with the representatives of the Mahayana schools. Sometime in the middle of the first post-Christian millennium they were joined by the Tantric scholars and masters of the Vajrayana tradition. What was at stake, apart from one’s personal reputation, was of course the “true Teaching”, which had to be vigorously defended. But since there were many different interpretations of the “true Teaching”, the debates were correspondingly heated. The Buddhist spirit of debating the Dharma, or Teaching, is best expressed by an anecdote told of the tenth-century Zen Master Ummon (Chinese “Yun-men”). Ummon, who was one of the great “staff-wielders” of the Zen school, once drew a line on the ground with his staff and stated enigmatically: “All the Buddhas, who are as numberless as the grains of sand at the river Ganges, are here heatedly debating the Buddhist Dharma.”

After centuries of sharpening their dialectical and rhetorical skills in Dharma com

bat with one another but also in dialogue with protagonists of other religious traditions, the Indian Buddhists encountered their most formidable opponent at the end of the eighth century A.D. That great antagonist was none other than Shankara, the most illustrious spokesman of the nondualist school of Hinduism. Shankara was to Hinduism what St. Thomas Aquinas was to Roman Catholicism. He helped usher in a great renaissance for Hinduism, which in the end led to the decline of Buddhism in India.

During his short but rich life, Shankara accomplished two important things. First, he formulated a philosophical system that could stand up to the sophisticated doctrines of Mahayana Buddhism. Indeed, his philosophy has much in common with Buddhist idealism, and both he and Gaudapada, his teacher’s teacher, have sometimes been charged with being crypto-Buddhists. Second, Shankara introduced into Hinduism the monastic ideal, which had proven so workable for over a millennium in the traditions of Buddhism and Jainism. This innovation greatly enhanced Hindu learning and creativity, and the ten monastic orders established by Shankara produced a galaxy of erudite defenders of the Vedic faith.

Shankara traveled widely throughout the Indian peninsula and defeated numerous rivals in debate. According to Taranatha’s history of the development of Buddhism in Tibet, the great Buddhist logician and dialectician Dharmakirti won in a crucial Dharma battle against Shankara. But this is only a pious wish, since Shankara lived at least a century after Dharmakirti. Not surprisingly, therefore, we find no reference to such a debate in the traditional biographies of Shankara.

Easily Shankara’s most memorable encounter was with Mandana Mishra, who was the most influential thinker and debater of Vedic ritualism at that time. The traditional Shankara literature has a record of their Dharma combat.6 According to the account given in Madhava Vidyaranya’s biography of Shankara, Mandana Mishra welcomed the renunciate Teacher with a volley of ill-tempered questions, which elicited humorous remarks and pointed quips from Shankara. Mandana is portrayed as losing the first round in this battle of wits. Seeing that he could not unnerve his visitor by invective and insinuations, he made an offering of alms to Shankara.

6. The earliest historical accounts were written more than one hundred years after the apparent incident. It appears there was a debate resulting in Mandana Mishra’s conversion, but records of the encounter vary and thus exact historical details are unclear.

But that great Preceptor replied that he had not come for edible alms but for the “alms” of disputation. He declared that, as was proper, the wager in the debate should be that the defeated should become the disciple of the victor. Mandana, proud of his erudition, readily accepted, saying that all his life he had been waiting for a fit opponent. He appointed his learned wife Bharati as umpire.

The debate is said to have continued over many days, attracting more and more learned folk. But in the end it was Mandana Mishra who found himself cornered by Shankara’s cogent argument. Then, as some stories would have it, his wife (who later revealed herself as the Goddess of Learning) intervened, arguing that Shankara had defeated only the one half of Mandana and that he should now debate with her. Shankara agreed and for seventeen days disputed with her on a whole range of themes. At last, cunning Bharati turned to the erotic arts. Shankara, the ascetic, promptly asked for an adjournment of several weeks so that he could acquaint himself with the theory and practice of erotics. In solitude he went into deep meditation and, through his yogic powers, entered the body of King Amaru, who was about to be burned on the funeral pyre. Reanimating the corpse, Shankara then assumed the king’s life and role. In this way he acquired, without breaking his vow of renunciation, the practical knowledge in erotics that only householders possess. He soon defeated Bharati, and Mandana Mishra adopted the life of an ascetic. U nder the name of Sureshvara he was to become one of the great protagonists of Shankara’s school of thought.

Dharma debates were an important feature of the religious and cultural life throughout the first millennium of the Christian era. Certainly in the Buddhist tradition they were so prominent that, in the seventh century A.D., the renowned Buddhist scholar Shantideva considered vada vidya, or rhetoric, as a science to be avoided in that it promoted a sterile intellectualism rather than Realization. Early in the Christian tradition, St. Paul (First Corinthians 2:4) made a very similar objection, arguing that conversion is a matter of grace, not of intellectual persuasion.

But Paul’s aversion to dialectics and rhetoric did not prevent the Christian intelligentsia from employing and developing, over the centuries, those “sciences” inherited from the Greeks. Today, with the growing recognition that our lives are interdependent, the concept of dialogue has achieved a new significance and importance. Some Christians are spearheading the “ecumenical” movement (even while their fundamentalist counterparts are tending to suppress free religious exchange). In its more narrow (ecclesiastic) orientation, ecumenism tries to accomplish Christian unity throughout the world. But in its wider, secular orientation, it seeks to establish an ongoing religious dialogue between representatives of all religious traditions of the world.

But this dialogue is only in its beginning stages. It is for the most part a far more subdued affair than was customary in the past. In part this is the result of an understandable cautiousness, born of tolerance. But in part it may also be a symptom of the widespread sense that truth is relative and that belief systems cannot stand up to the scrutiny of the discriminative mind. Because the “contemporary man” (whether nominally religious or not) has not explored the experiential, participatory domain of higher religious and spiritual consciousness, such an individual tends to believe that one metaphysical system is as “true” as any other. And most are ignorant of the tradition of God-Realizers who have achieved true gnosis of the Transcendental Reality. In the last analysis, such a stance embodies an uncertainty about the very existence of spiritual reality, and therefore it also embodies a lack of commitment to or understanding of the process of selftranscending spirituality.

Would it not be possible to have a more forceful dialogue, without falling into sectarian proselytizing? Is passion for one’s way of life necessarily irreconcilable with tolerance? Should one settle for mere “mutual understanding” or the search for possibly spurious parallels and areas of overlap? Or does such an approach simply signal that we wish to preserve each other’s immunity as “believers”? Would we not benefit from a deeper, more challenging consideration of the whole matter of spirituality, risking more than words or dogmas and intellectual systems—risking ourselves?

Christian ecumenists are still searching for a common basis in their dialogue with members of other religions. There is beginning to be more of a recognition that such a common ground will not be found on the level of belief or doctrine. As Yves Raguin, Jesuit and professor of Chinese Studies, observed: “To have a real dialogue we have to confront each other’s experiences on a deeper level than in words, a level beyond any possible expression.”7 Raguin proposed as the “ultimate” common ground that “all men are bound to God by a destiny which is inscribed at the depth of their being.”8 What he means by this is that the human individual has been fashioned in the likeness of God. But this notion is so distinctly Christian that, for instance, few Buddhists would be able to relate to it. It still remains on the level of doctrine.

7. Y. Raguin, “Dialogue: Differences and Common Grounds”, in S. J. Samartha, ed., Faith in the Midst of Faiths: Reflections on Dialogue in Community (Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1977), p. 74.

8. Ibid., p. 76.

An altogether different approach is possible, and that is for religious dialogue to be religious, or spiritual, not only in its content and intention, but also in its method or presentation. In other words, the spiritual orientation, or active practice of selftranscendence, of the participants in the dialogue can serve as a genuine common basis for the meeting of minds and hearts. Indeed, it should be obvious that such selftranscendence provides the only possible foundation. The feasibility of this is demonstrated in the Dharma combat of the great masters of antiquity: More than any skillful argument, it was primarily their spiritual comportment and presence that decided the outcome of the debate. That is to say, what mattered was not so much their knowledge as their being.

In his “Song of Enlightenment”, the Chinese master Hsuan Chueh (or Yung Chia), whose Enlightenment was confirmed by the Sixth Patriarch Hui Neng, exclaims: “Roll the Dharma Thunder and beat the Dharma drum.” No doubt he knew that when the self is eclipsed by the True Being, there is no lack of energy and wisdom; and that Dharma combat is not polite table-talk, but a fierce, if loving, confrontation with Truth.

Few mystics and Adepts have been in accord with Wittgenstein’s comment that “whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Those who bubbled over with the Joy of God, or the Bliss of Reality, have always been compelled to reach out and communicate with others. Gautama the Buddha and Shankara Acarya are the best traditional examples. Both lived the life of an ascetic, and yet they worked tirelessly for the spiritual upliftment of humankind, and neither shied away from argumentation, dialogue, and controversy. They fearlessly spread the Dharma, by way of compassionate Instruction and not least by their own example. And their great disciples did the same.

Clearly, the world’s great religious traditions leave room for dialogue as a form of spiritual practice. Today, more than ever, there is a real need for considering the perennial issues of human life and the great Way pointed to by the Realized Adepts past and present. And such dialogue necessarily leads beyond all proselytizing and the egoic defense of one or another ideology or belief system. What matters, and what has always mattered, is Truth Itself. ■