A Talk by the Vajra Regent Osel Tendzin

originally published in

The following talk was given by the Vajra Regent Osel Tendzin to the Vajradhatu sangha at Lyndon State College, in Lyndonville, Vermont, on May 27, 1987.

“If you have to generate something in your mind, the best thing to generate is the memory of the guru, which is the same as your yidam”

***

Good evening. I was requested to make a talk this evening. The Dorje Loppon suggested I say something after the cremation, and I thought that would be good, if just simply to mark the time.

In terms of the past, present and future, in the 17 years that the Vidyadhara taught in our world, we trained our minds, tamed our minds, we learned dharma, both buddhadharma and Shambhala. We learned how to practice meditation. We learned how to regard phenomena as empty, we learned how to generate kindness and compassion, bodhicitta, for ourselves and others, and we learned how to practice the vajrayana path of transmuting confusion into wisdom. So in the 17 years of his teaching, he presented the full-blown three-yana journey to all of us, and depending on our capacity, we have been able to absorb that teaching and practice. So that’s why at this particular time, which we could call the present, everything is vividly real in emptiness.

The cremation itself seemed to mark that passage of time in that the past is marked by the present moment, and the present moment points to the future. It seemed to me that, especially since his death and particularly yesterday, all of our training became obvious, and that the future is the legacy we have inherited. For myself, there’s a particular legacy of the transmission of the Trungpa line and especially, the teachings of meditation in the mahamudra lineage. Aside from that specific transmission, what we’ve received is a total view of the mandala principle altogether, which actually goes beyond technique, so to speak.

The’.future is mind’s projection, since it doesn’t exist, at least right now. We can project what the future will be like. I think most importantly we should keep in mind the intention of our teacher, our root guru, and that intention appears to be twofold: firstly, to free the individual from the obstacle of believing in a self, or as we say, ego, and secondly, to create enlightened world or to reveal the world as an enlightened mandala or sacred mandala.

I was talking to a reporter and he asked me what I thought was the significance of this cremation. I said that when Buddha died, entered parinirvana, then his teaching became like space, permeated the environment, and that’s the way we regard Rinpoche’s death. In terms of the transmission of the awakened state of mind, Trungpa Rinpoche was such a great teacher that all of his students received it. It wasn’t the province of one particular person. Just as Buddha himself transmitted the essence of the teaching, which exists at this very moment, so in the same way the Vidyadhara transmitted the essence of the teaching.

The confidence in that is the confidence to fulfill his wishes in our lifetime. There is obviously a tremendous sense of loss that cannot be denied. Somehow, waking up in the morning is not the same. For myself there is a constant feeling of death, which is so central to the Buddha’s teaching. Milarepa said that if you don’t remember death, you are wasting your time. Trying to practice the dharma and learn certain rituals and mantras might make you accomplished at those things, but at the time of death, if you don’t remember, it doesn’t make much difference.

Now that could give rise to a rather depressing point of view. We could look at the rest of our lives as simply a preparation for death, which might be depressing if you don’t really want to get anything done in the world except practice those rituals which would prepare you for death. And since we don’t really know how many mantras it would take, it makes us somewhat edgy, which is Rinpoche’s great legacy to us: no guarantees, and a constant sense of intelligent paranoia.

I once asked Rinpoche about whether it is better to become a monk because I had heard that it is easier to attain enlightenment through that path. He said. “Yes. that’s true. However, if you take care of your family, that is much better for the world and everybody in it.”

I once asked Rinpoche about whether it is better to become a monk because I had heard that it is easier to attain enlightenment through that path. He said. “Yes. that’s true. However, if you take care of your family, that is much better for the world and everybody in it.” So we have been given this particular path, which is a very difficult one in terms of living in the world and taking care of things, because things beget other things. Somehow you never seem to get rid of things. Every time Rinpoche decided to begin a new project, it would make all of us nervous, because we had usually just finished something to the degree we felt proficient and accomplished, and we had to begin something else. That kind of legacy is really important for us in realizing how strong his compassion was for all sentient beings. He would endlessly embark on different projects. It wasn’t simply just to keep people busy; however, that helped. It helped in two ways: it helped to calm the mind, and it also helped to create benefit for future practitioners. So when we look at all the different forms of Vajradhatu and Nalanda Foundation, and the Shambhala teachings, there are so many things to attend to. so many things to accomplish. However, we have such a great example in our lifetime—someone who lived and in a very short time actually transformed the world as we know it. All of us have a share of that inheritance, and it’s startling and shocking but very basic.

It is my wish that we will continue in his way, with his intention. For myself and the Vajradhatu and Nalanda administrations, we intend to make it grow and spread throughout the world. At the same time, we should not forget our personal and individual realization, which is to say, we should practice as we’ve been taught, so that as we realize more and more, we can actually fulfill his wishes. It is a personal journey but at the same time it’s completely wide open.

One of the things I remember most dearly about Rinpoche was his willingness to accommodate chaos. In fact, we could say he was the lord of chaos, and therefore the king of mahasukha. I don’t have any particular doubt about chaos and the intelligence in the chaos. I am simply amazed that that enlightenment experience has been transmitted to so many people. Intelligent chaos is the nature of our minds in any case. We should not step back from that. Being put on the spot is the very best training and also the very best expression of the awakened state of mind.

I’m sure that all of us have some feelings of anxiety or uncertainty about the future. When the unsurpassable guides passes into the parinirvana and becomes the dharmakaya, students like ourselves feel uncertain about whether we have the stamina to attain that perfect enlightenment. However, I have great faith in the power of the teaching because so far I have not seen any error, any mistake. What we do with our life, including our mental life, is extremely important for the future. And the basic thing is not to do anything at all, that is, mentally.

If you have to generate something in your mind, the best thing to generate is the memory of the guru, which is the same as your yidam. If you practice vajrayana sadhanas and you visualize Vajrayogini or Cakra-samvara. that’s the best thing you can do with your mind. If you practice the mahayana discipline, the best thing you can do with your mind is to exchange yourself for others because that’s basically the wish of the guru. And if you practice hinayana discipline, the best thing you can do with your mind is to practice in a hinayana way—not taking thoughts to be solid. In that way you are never separated from the essence of the teaching. But altogether it’s best not to do anything.

I was reading the Mandala Sourcebook today, and Trungpa Rinpoche said that when presented with this particular teaching people would say, “Don’t you think there’s a problem with the world? There’s so much aggression, there’s so much pain, so much that needs to be done. Don’t you think we should do something?” And I think the point is that if you can actually master not doing anything, then the action that proceeds will be beneficial.

So please take that to heart. It’s not a question of forcing yourself to be still. It’s more a question of recognizing the completeness of one’s own experience. And since we as Buddhists don’t particularly talk about any origin to experience, then we should not try artificially to generate some state of mind we consider spiritual or enlightened. It appears that everything happens all at once, so the simple freshness of ordinary mind is the best thing.

I think it’s very good for us to get together like this. In the future, whenever we have the opportunity we should do so. Maybe the term “ganacakra” is appropriate, a vajra feast, a feast of dharma, but more precisely, a feast of things as they are.

“I think it is important for us to continue Rinpoche’s teaching about how to relate with the sacredness of the phenomenal world—how we should relate with our children, our friends, our relatives, our employers and employees, in other words, how to make the world into the sacred world of the warriors of the Shambhala teachings.”

We have been taught all the various methods, and I’m confident that all of those methods will bring us to the experience of one taste, which can allow us to progress on the path towards Buddhahood. In particular I think it is important for us to continue Rinpoche’s teaching about how to relate with the sacredness of the phenomenal world—how we should relate with our children, our friends, our relatives, our employers and employees, in other words, how to make the world into the sacred world of the warriors of the Shambhala teachings. That means the body has to be respected, not thinking that the body is permanent, but recognizing it as a vehicle for the teachings and for the expression of the awakened state. Phenomena have to be appreciated in terms of seeing perceptions as vividly real and sacred and, at the same time, empty. We also have to pay attention to the emotional world, because when seen clearly those emotions are expressions of wisdom.

So we have a lot to do and not much to do. Make it simple. Well, that’s all I have to say. You take care of yourselves. I hope we’ll be seeing each other. And wherever you’re going you should all remember that you are part of that legacy of Trungpa Rinpoche, so all of our minds are together on that. And in your body, speech and mind you should freely display that to the world, because it will be of benefit to everybody. Thank you.

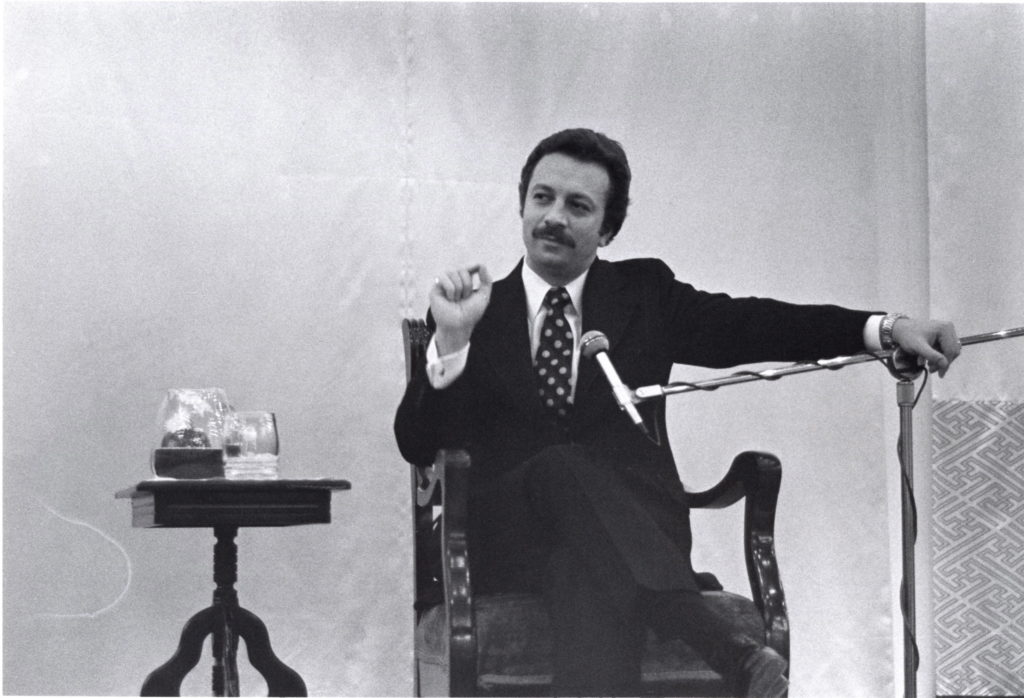

Osel Tendzin on first meeting Chogyam Trungpa in February 1971

“How could anybody be solidly there like a rock, like a monument, and yet be empty at the same time?”

I met the Vidyadhara on a Sunday afternoon at his home in Four Mile Canyon. I was wearing a red ruffled shirt and red velvet pants, a la L.A., and was sporting long hair and a beard. I was ushered into the sitting room, where I was confronted by a person much younger than I had expected, surrounded by several students, some of whom I knew from my previous stay in Boulder. With a piercing gaze that seemed to comprehend my entire history, he greeted me courteously. We had a conversation in the company of his students, which lasted perhaps twenty minutes. He asked about Swami Satchitananda’s whereabouts and inquired as to his health. I invited the Vidyadhara to the so-called World Enlightenment Festival. He said that he would have to check his schedule, and I departed, not failing to notice a bottle of Johnny Walker Red Label and a glass jar of orange juice beneath the table in front of him. I recall driving down from Four Mile Canyon in a quizzical mood, which began to expand as the evening wore on. This particular mood took shape in the form of a question, which itself described the experience of meeting the Vidyadhara, and described my first taste of How I Met the Vajra Master, Buddhism as well. I had met many teachers, but none had ever evoked this question. I thought to myself, over and over, ““How could anybody be solidly there like a rock, like a monument, and yet be empty at the same time?” Those were my exact thoughts….

…… in March of 1971, I rang up the Four Mile Canyon house, said I had been invited to visit and asked when I could come up. The voice on the other end seemed rather sharp, and said that I could come by tomorrow. I did, and when I arrived I was How I Met the Vajra Master seated in the breakfast area off the kitchen and told to wait. As I sat there by myself feeling completely out of place, as if I had a gigantic head, arms, and legs, various students walked by without saying hello or inquiring who I was. Needless to say, that made me even more apprehensive and unsettled. After about an hour or more, I suddenly looked toward the doorway leading to the kitchen, and at that moment the Vidyadhara appeared. He walked slowly but directly to the table and sat down next to me. “Hello. So you’re here,” he said, after which he said nothing for what seemed to be fifteen minutes. He had an eight-ounce glass of scotch in his hand. When it had been refilled, he turned to me, lifted it, and said, “Here.” I had not had a drink of liquor in five years, and I asked him, “Is this prasad?” which, loosely translated, means “the guru’s grace.” “Yes,” he said. “That means you have to take three big sips,” which I did. After a while, he said, “Three more,” and still later, “Three more.” Years later, he remarked that the incident was like the first meeting of Gampopa and Milarepa.