Rick Fields

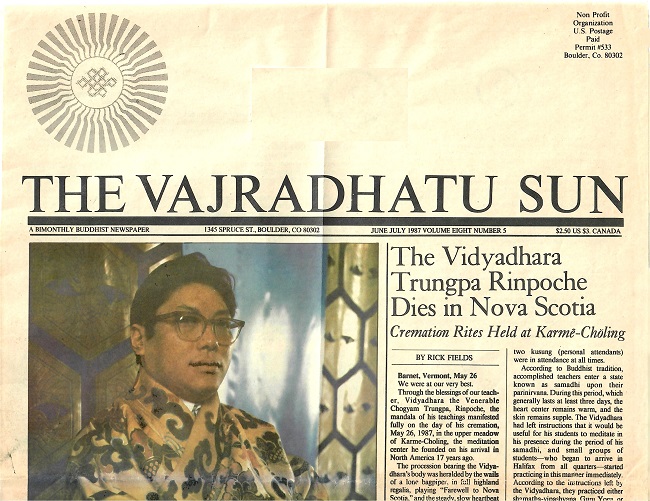

Barnet, Vermont, May 26, 1987

We were at our very best.

Through the blessings of our teacher, Vidyadhara the Venerable Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche, the mandala of his teachings manifested fully on the day of his cremation, May 26,1987, in the upper meadow of Karme-Choling, the meditation center he founded on his arrival in North America 17 years ago.

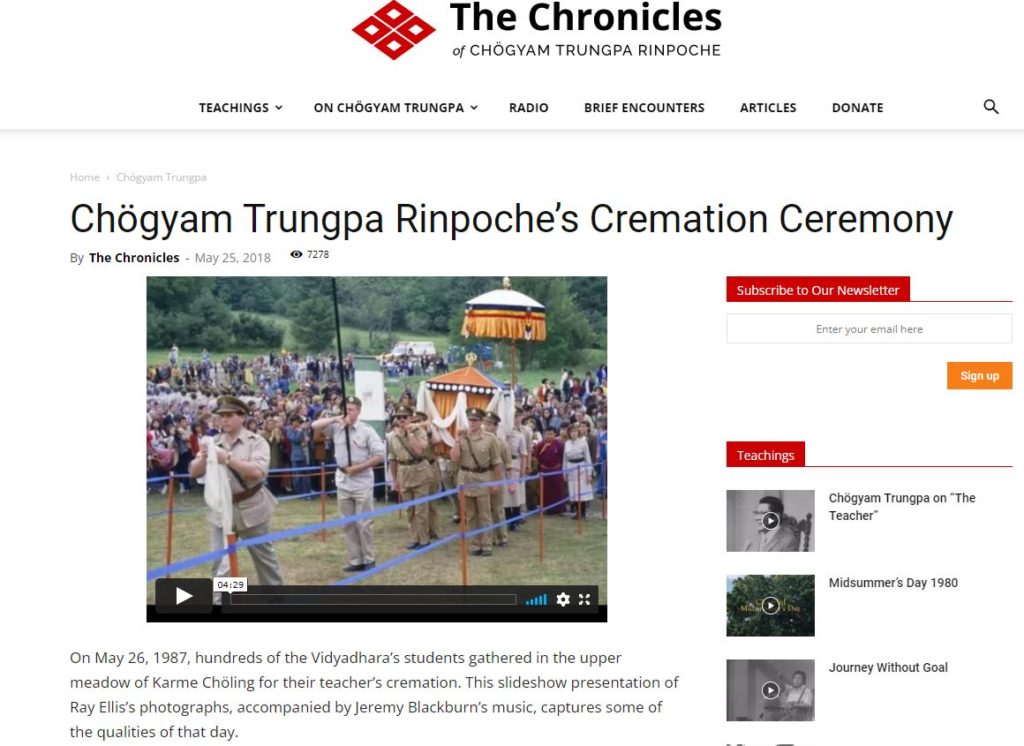

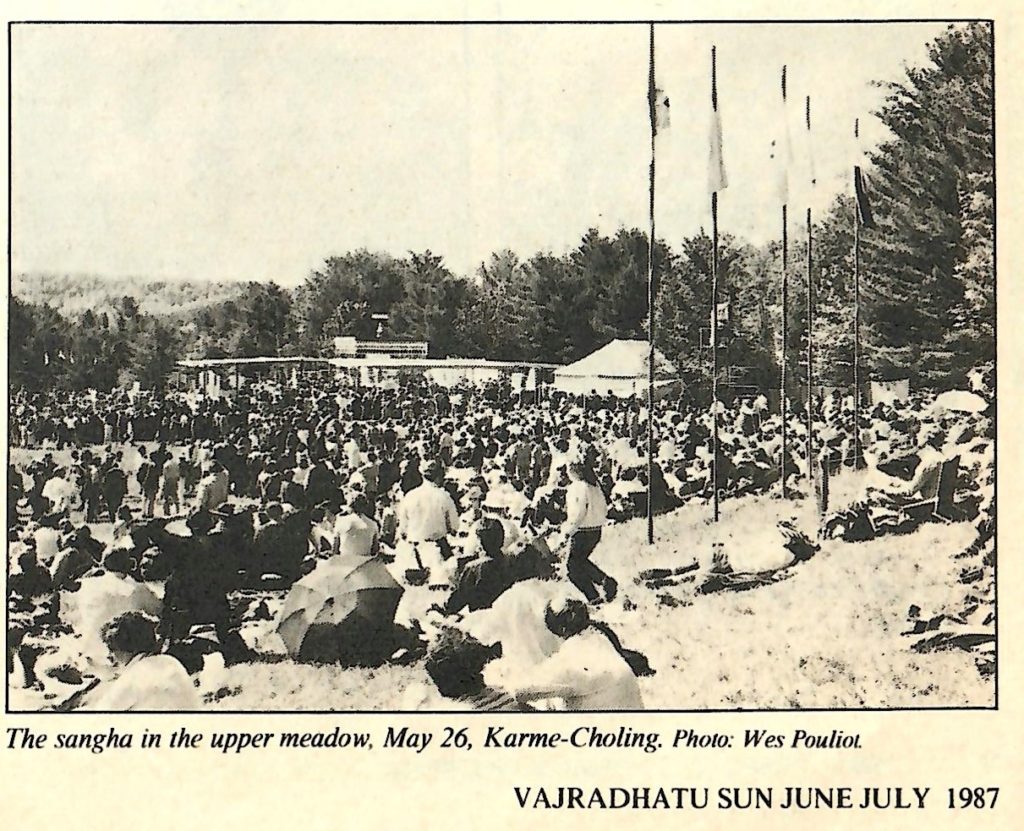

The procession bearing the Vidyadhara’s body was heralded by the wails of a lone bagpiper, in full highland regalia, playing “Farewell to Nova Scotia,” and the steady, slow heartbeat of a deep bass drum. An honor guard of Dorje Kasung, khaki-clad, and marching six abreast in slow, meditative cadence followed. A crowd of more than 3,000 watched in silence as the procession emerged from the forest and passed beneath the Tori gate, which marked the entrance to the meadow and the cremation site.

The Vidyadhara had passed away on April 4, 1987, in Halifax, Nova Scotia. For six months previous to this, he had been ill ever since he suffered a cardiac arrest and respiratory failure in Halifax on the afternoon of Sunday, September 28.

The Vidyadhara’s parinirvana, which took place in the Intensive Care Unit of the Halifax Infirmary, was witnessed by his wife, Lady Diana Mukpo, his eldest son, the Sawang Osel Mukpo, and the Vajra Regent Osel Tendzin, his American-born successor, as well as by a number of his closest students. Just before his parinirvana, the Vidyadhara opened his eyes, and looked slowly and calmly around the room. At that moment, the assembled company spontaneously sang the Shambhala Anthem in muted tones, and when they had finished the Vidyadhara had entered parinirvana.

Though his passing was not completely unexpected, it nevertheless came as a great shock to the Vajradhatu community. As one student said, “It was as though a huge hole had been torn in the fabric of the universe we had known.” It was—and still is—hard to imagine a world without him.

The Vidyadhara had left precise instructions for the ceremonies following his parinirvana. Following these instructions, his body was immediately bathed in saffron water, and marked with certain seed syllables. He was taken to the Kalapa Court, dressed in a gol chuba and red meditation hat, and seated in the meditation posture on a brocade covered throne. An honor guard of two kusung (personal attendants) were in attendance at all times.

According to Buddhist tradition, accomplished teachers enter a state known as samadhi upon their parinirvana. During this period, which generally lasts at least three days, the heart center remains warm, and the skin remains supple. The Vidyadhara had left instructions that it would be useful for his students to meditate in his presence during the period of his samadhi, and small groups of students—who began to arrive in Halifax from all quarters—started practicing in this manner immediately. According to the instructions left by the Vidyadhara, they practiced either shamatha-vipashyana, Guru Yoga, or the Vajrayogini sadhana.

The samadhi ended after five days, and a few hundred sangha members gathered outside The Kalapa Court as the Vidyadhara’s remains were taken by motorcade to the Halifax airport, and then by charter plane to Burlington, Vermont, and finally to the shrine room at Karme-Choling in Barnet, Vermont.

At Karme-Choling, the Vidyadhara’s remains were placed in a sitting posture in a brocaded upright box, which in turn was placed on a shrine in the center of the shrine room. Again, an honor guard of Dorje Kasung and Kusung was in attendance, with one Kusung slowly circumambulating the shrine. A stationary Kasung marked the time, every fifteen minutes, with wooden clappers. The body was preserved by a traditional Tibetan method that uses salts, camphor, and various herbs.

The shrine was ringed by 108 butter lamps, and embellished with the Vidyadhara’s personal effects, including his robes, his grey suit, photographs, and his personal shrine implements on all four sides. As in Halifax, groups of students began to practice meditation around the clock.

Arrangements for the cremation had begun in Halifax with calls and telegrams to the four principal regents of the Karma Kagyu lineage—H.H Shamar Rinpoche, H.E. Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, H.E. T’ai Situ Rinpoche, H.E. Gyaltsap Rinpoche— in India, Nepal, and Sikkim, as well as to His Holiness Dingo Khyentse Rinpoche, one of the Vidyadhara’s principal teachers, and one of the major teachers of the Nyingma lineage, in Nepal. Arrangements for the cremation had begun in Halifax with calls and telegrams to the four principal regents of the Karma Kagyu lineage—H.H. Shamar Rinpoche, H.E. Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, H.E. T’ai Situ Rinpoche, H.E. Gyaltsap Rinpoche— in India, Nepal, and Sikkim, as well as to His Holiness Dingo Khyentse Rinpoche, one of the Vidyadhara’s principal teachers, and one of the major teachers of the Nyingma lineage, in Nepal.

Arrangements and work intensified at Karme-Choling, which shortly became an example of the Tibetan “tent culture” the Vidyadhara had introduced to house the Vajradhatu Seminary at Rocky Mountain Dharma Center in northern Colorado. As hundreds of volunteers began arriving at Karme-Choling, they were housed in tents trucked in from RMDC. The Dorje Kasung occupied an entire self-sufficient tent camp on higher ground. Temporary bathhouses were built, the kitchen upgraded and resupplied, and a small hotel in Barnet that had been bought coincidentally to augment Karme-Choling’s housing was completely gutted and restored to serve as home, called Ashoka Bhavan, for the large party of Tibetan lamas and monks who were expected for the cremation ceremonies.

The central focus of all this activity was the construction of the traditional cremation stupa for a high lama—a purkhang (literally, “corpse palace”), which was built in the upper meadow, as well as the four canopied platforms surrounding the Purkhang itself. Built out of cinder block and white plaster, with decorations painted by Ngodrup Rongae and various helpers, the Purkhang stood about 25 feet high, and was surmounted with a gold spire.

The day for the cremation had been set as May 26 by His Holiness Dingo Khyentse Rinpoche. As it turned out, it was just barely enough time (or just the right amount of time) to properly prepare the site and develop the logistics needed to host the estimated 2,000 to 5,000 people expected.

Everyone taking part in the preparations found themselves playing a part that fit like the missing piece of a puzzle into the larger whole. There were throne seats to be built for the visiting lamas. The sewing room seamstresses worked through the night more than once. The kitchen staff (assisted by regular rota assignments from all) accomplished miracles daily. Carpenters, painters, construction workers, office workers, road builders, housing finders, transportation coordinators, administrators, translators, drivers, attendants, housekeepers, and suppliers—we were all stretched to the limit and then beyond, and beyond again. “Don’t Take Anything Personally” was the useful motto that came out of the morning work meetings.

At a certain point, it became apparent to everyone working at Karme-Choling, as well as those of its who helped in so many ways from our homes, that the entire experience of the Vidyadhara’s parinirvana, including the preparations for the cremation itself, were simply and splendidly a confirmation and extension of our training with the Vidyadhara. As usual, he had once again pushed us beyond our own conceptions of what brilliant world of the guru.

Still, the center of the mandala we were so busily creating was the shrine room where a steady stream of students, friends, and visitors came to pay their last respects to the Vidyadhara. Practice went on continually and intensified, particularly after the visiting lamas and monks arrived. His Holiness Shamar Rinpoche, the present head of the Karma Kagyu lineage, arrived first.

The main party of lamas and monks—including now H.E. Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, H.E. T’ai Situ Rinpoche. H.E. Gyaltsap Rinpoche, as well as the Ven. Beru Khyentse Rinpoche, the Ven. Surmang Gar-wang Rinpoche, and the Ven. Dabsang Rinpoche—arrived just a day or two before completion of the Ashoka Bhavan. The last to arrive was H.H. Dingo Khyentse Rinpoche, at 77 the most senior of lamas, and his party—the Ven. Sechen Rabjam Rinpoche, the Ven. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche. Ven. Tulku Perna Wangyal. Ven. Trulshig Rinpoche, and Ven. Pewal Tulku Chi-Me Dorje Rinpoche, a teacher from Dzokchen Monastery who had just recently managed to leave Tibet.

The Tibetan monks and lamas performed pujas and feasts in the shrine room in Tibetan, while we did ours in English (and others simply practiced sitting meditation), and it all worked wonderfully. A great silence reigned in the midst of a great cacaphony.

The morning of the day of the cremation a thick, foggy mist hung like a canopy over the hills. At the top of the road leading to Karme-Choling, the Dorje Kasung and Vermont State Troopers directed traffic. Buses from Dunbar’s Field in Barnet, which acted as a staging area, came, unloaded, and went back. The Dorje Kasung managed to orchestrate the arrival of thousands of people, seemingly all at once, with humor and precision. As a reporter for the St. Johnsbury Caledonian-Record wrote about the over the Karme-Choling grounds, dressed in khaki uniforms, checking visitors at the gate, directing traffic at the road, and instructing people where to park. An aura of crisp efficiency, combined with friendly expectancy, gives a feeling that everything will run smoothly.”

The morning of the day of the cremation, the procession broke out of the woods and came into view just as the fog began to lift. The bagpipe’s wail mingled with the bass drum and the deeper wail of the long Tibetan horns played by the party of monks following the slow marching ranks of kasung. The body was carried in a canopied, silk-curtained upright box, a palanquin on the shoulders of eight of his closest students, with an incense bearer and the Vidyadhara’s Trident standard leading. A traditional round embroidered parasol followed held high above the palanquin.

The Vidyadhara’s wife. Lady Diana Mukpo. his eldest son. the Sawang Osel Mukpo. and the Vajra Regent Osel Tendzin. followed, along with other close students, including members of the Vajradhatu Board of Directors.

The procession entered the Purkhang area, and the palanquin bearers climbed a stairway and placed the upright box bolding the body into the Purkhang itself. A cannon fired, and flags raised. Khatas and other offerings were then made in front of the Purkhang. to the east, by the visiting teachers and monks, the family, and visiting dignitaries, including former Canadian High Commissioner to India James George, the ambassador from Bangladesh. Obaidullah Khan. Zen Masters Kobun Chino-roshi, Jakusho Kwong-roshi. Tetsugen Glassman Sensei, and John Daido Sensei. Then the entire sangha began to pass in front of the Purkhang with their offerings.

The principal practice, as is. traditional at cremations, was the fire puja. The fire represents purification. As David Rome, for many years the Vidyadhara’s personal secretary explained to reporters, the fire puja “helps students clear out obstacles to understanding, and reaffirms their connection with the teacher, particularly the mind of the teacher.” During the fire puja various substances were offered. These included ghee, black sesame seeds, grains, grasses, juniper, willow branches with tiny lotuses carved at the tip, betel nuts, torma, small amounts of powdered gems and metals, including pearls, turquoise, silver, gold, copper, and iron.

Four different types of fire pujas were performed simultaneously: H.H. Khyentse Rinpoche and party on the east, H.H. Shamar Rinpoche and party on the west, H.E. Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche and H.E. Gyaltsap Rinpoche and their parties on the south, and Lady Diana, the Vajra Regent Osel Tendzin, the Sawang Osel Mukpo, and senior Vajradhatu students on the north. (H.E. T’ai Situ Rinpoche had left the day before for a previously scheduled meeting with the Pope.)

Around eleven a short tea break was taken, and the gold spire atop the Purkhang removed. Just after twelve, with the pujas resuming, the fire at the base of the Purkhang was lit by a monk, who, as required by tradition, had never met the Vidyadhara. The cannon fired once more, and a lone trumpeter played the Shambhala Anthem, which was joined by Tibetan horns. As the small canopy above the Purkhang caught fire, orange flames shot into the now bright blue sky.

About 20 minutes after the fire had been lit, Shibata Kanjuro Sensei, Imperial bow-maker to the Japanese court, and three of his students performed a traditional ceremony done when an emperor dies. At the four corners of the Purkhang, they plucked empty bows, and then offered straw sandals to the fire.

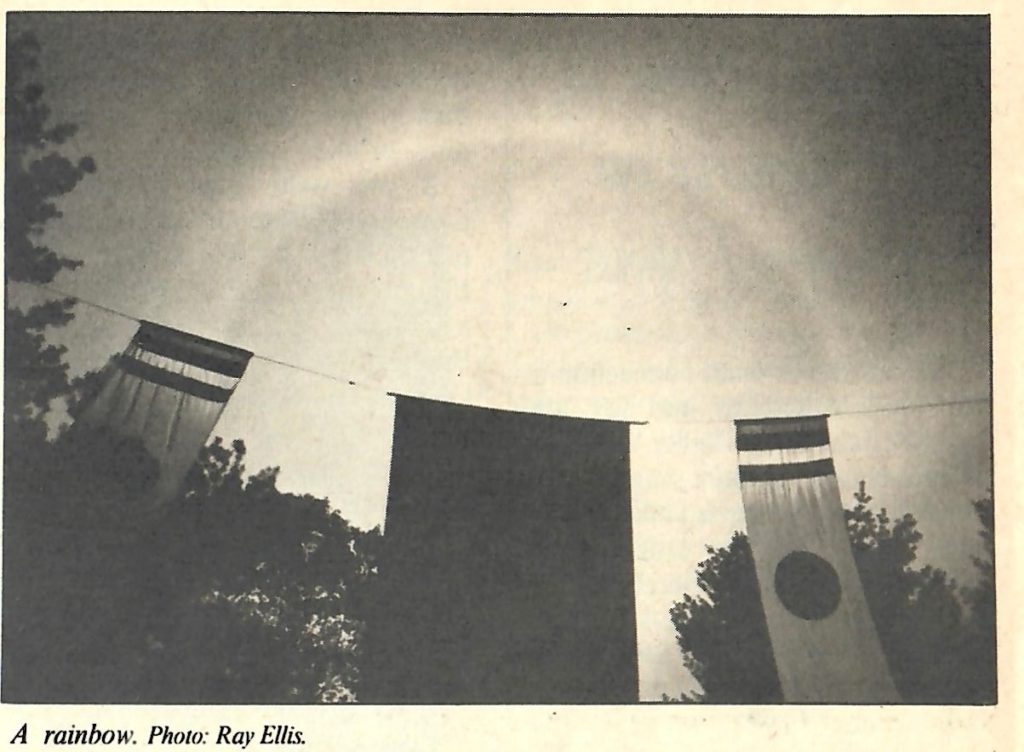

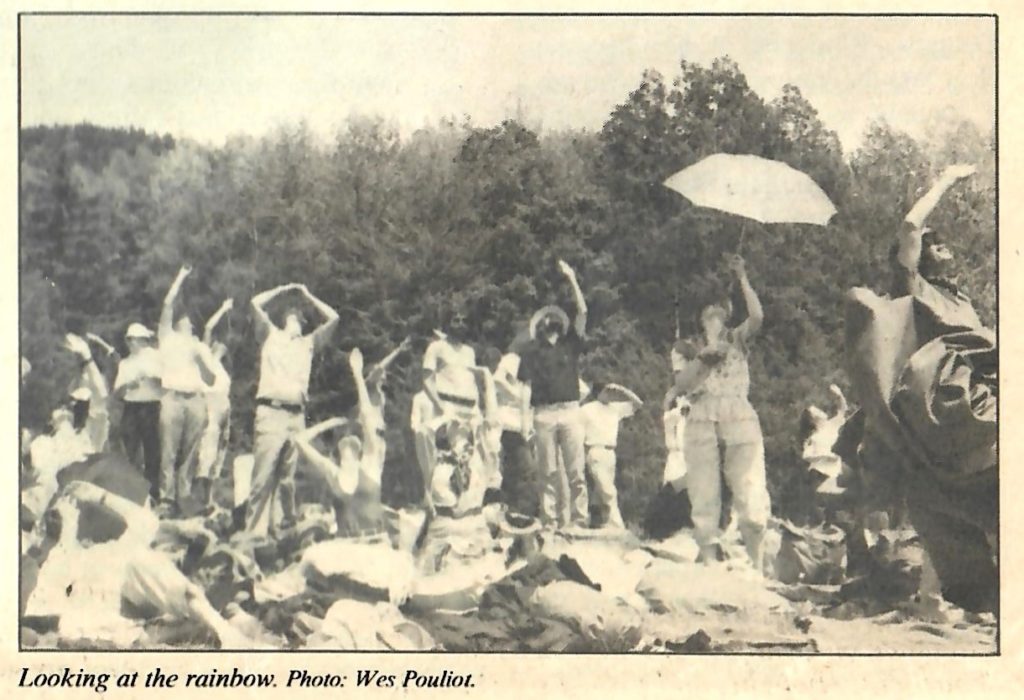

Practice continued. “And as the fire died down, a dramatic succession of rainbows colored the sky.” as the Burlington (Vt.) Free Press reported. In particular, a perfectly round rainbow circled the sun. A white cloud in the shape of an Ashe appeared, and three hawks circled and circled.

Ven. Tulku Pema Wangyal Rinpoche and Ven. Rabjam Rinpoche, later noted the auspicious signs associated with the cremation—first, the fog in the morning, which was neither too high nor too low, and which hung like a protective parasol over the area; then the rainbows; then the clouds shaped like khatas; and finally the three hawks, dakinis, who had taken the form of birds, welcoming the Vidyadhara.

When the pujas were finished, there was one announcement, the only announcement heard during the entire day. “Ladies and gentlemen, the Shambhala Anthem.”

And then, finally, the warrior’s cry that held, for that moment, all that he gave us: “KI KI SO SO ASHE LA GYEL LO TAK SENG KHYUNG DRUK DI YAR KYE!”

Also see: