“He is a blazing, roaring fire consuming all impurities to ashes.”

Ramakrishna speaking of Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda in America – New Discoveries

I have a message to the West as Buddha had a message to the East

Swami Vivekananda

1958

1958

PROLOGUE

I

Swami Vivekananda was born in Calcutta on January 12, ’63. His family, the Dattas of the Kayastha (Kshatriya) caste, as a wealthy and aristocratic one, long known for its charity, learning and spirit of independence. The Swami’s father, Vishwanath Datta, was an attorney in the High Court of Calcutta a position which, together with his inherited fortune, made it possible for his family to live in luxury. Out of his ample means Vishwanath gave to all who asked, supporting many of his relatives

—worthy and unworthy alike. The Swami’s mother, Bhuvaneshwari Datta, was of an equally generous nature. She cheerfully managed the large household, composed hot only of her five children but of her husband’s relatives, and somehow in the midst of her duties found time for the study of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, from both of which she could recite long passages and both of which she taught to her children. Thus Narendra Nath Datta, as Swami Vivekananda was known in his youth, was blessed with noble parents, even as they were blessed with a son whose influence was to usher in a new age.

Narendra as a child was, to say the least, difficult to manage. Impelled by a brilliant and energetic mind, he had a capacity of action and mischief that knew no limit. At times he would become uncontrollably restless, as though Lord Shiva, the Great God, the Absolute, to whom confinement was an outrage, dwelt in his small body. It is said that his mother’s only remedy for his turbulent outbursts was to pour a pitcher of cold water over the child’s dark head, repeating loudly the while the name of Shiva. At once Naren would grow calm and thoughtful, the clouds would disperse and soon his ordinarily joyful disposition would come to the fore. After such emergencies, Bhuvaneshwari Datta would sigh: “I prayed to Shiva for a son, and He has sent me one of His demons!”

But tempestuous as he was, Naren from early childhood had a predilection for meditation. He would play at it, sitting in yoga posture, and often play-acting would pass into deep self-forgetfulness. The boy also had an innate fondness for wandering monks who would come to the house for alms, and to the despair of his parents he would regularly give them everything he could lay his hands on—bauble or heirloom. The device of locking Naren in his room whenever monks approached was of small avail, for from his window objects of all sorts would come showering down to the feet of the sadhus.

As a boy Narendra was the favorite of old and young alike and a leader among his contemporaries, who willingly deferred to his greater imagination and courage in the invention and execution of elaborate games and pranks. But as Naren grew older his unlimited energy began to turn more and more from wild and furious playing to the pursuit by day of intellectual activity and by night of serious meditation, which came to him naturally and which brought spiritual visions to him, even in his early youth.

In 1877, when Naren was fourteen, his father found it necessary to move the family for a period of two years to Raipur in the Madhya Pradesh. In Raipur, where there was no school, Naren had time to spend long hours with his father, whose scholarship and openmindedness had led him, along with other Hindus, into a suspicion of his own cultural heritage and had bred within him an agnosticism typical of the age. Vishwanath gave careful attention to his son, training his keen intellect and directing his attention to the study of Western culture and knowledge, which in that day was considered to be the very acme of learning.

When Narendra’s family returned to Calcutta in 1879, he entered the Presidency College and, later, the General Assembly’s Institution, founded by the Scottish General Missionary Board. Never content with the offered curriculum, he read independently an untold number of books. His powers of reading and of retention were little short of miraculous. Able to consume and digest a weighty tome in a short time, he never again forgot a detail of it, and as a result there were many branches of Western learning, as well as of Eastern, in which he became well versed. Indeed, he acquired during his college life a thorough knowledge Western philosophy, history, art, literature, and a more than general

knowledge of science and medicine.

But Naren’s concern was not with accumulating a fund of knowledge, but rather with discovering ultimate truth. A more shallow mind would have remained content with, or been frustrated by, the agnosticism to which Western philosophy and science pointed. His thirst for a direct knowledge of reality, however, was profound and not to be put off by the well-acknowledged fact that it could not be acquired through the intellect or the senses. On the one hand, his spirit rebelled against the degrading philosophy of “I can’t know,” and on the other hand, it was impossible for him to accept on mere faith a doctrine that logic or his own experience could not verify. The result was mental torment and continual search.

During this period Narendra became a member of the Brahmo Samaj, a society which was at the time the spearhead of a reform movement among the Hindus. Its position was both modern and orthodox. While it advocated many social reforms and protested the old tenets of orthodox Hinduism, such as polytheism, image worship, the doctrine of Divine Incarnations and the need of a guru or spiritual teacher, it decried at the same time modern atheism and taught a belief in and worship of a monotheistic God, a formless God with attributes. In the doctrines of the Brahmo Samaj and also in one of its leaders, Keshab Chandra Sen, young Bengal saw hope for a modernized Hinduism. With characteristic energy and enthusiasm, Naren identified himself with a branch of the Samaj led by Siva Nath Sastri and Vijay Krishna Goswami and heartily concurred in its attempts to sweep away the incrustations of the ages. He accepted the doctrine of a formless God with attributes, but unlike other Samajists, desired to see Him, as it were, face to face, for to him religion was of as little use as was intellectual learning if it did not bring him into direct contact with the very heart of reality.

Naren was now eighteen, well built, of startling attractiveness, strong and independent intellect and sparkling wit. He was an accomplished singer and a fascinating conversationalist whose moods could vary from the profound to the playful. Always guided by a highly developed moral sense, he observed the utmost purity in his life—an effortless, innate purity which was never dampening. Indeed, wherever Naren went he was the center of interest and gaiety and was loved and respected by all. It would have been a simple matter for him to reach the heights of worldly power and fame. Yet so restless was his spirit for an intimate knowledge of God that had he thought it necessary to renounce the world to attain it, he would gladly have done so. But how to know God? Was it possible to know Him? “Sir,” he asked Devendra Nath Tagore, who was looked upon as one of the best spiritual teachers of the time, “have you seen God?” Instead of answering, Devendra Nath blessed him and said: “My boy, you have the yogi’s eyes.” Again and again Naren asked the question, putting it to the leaders of various religious sects in Calcutta, to pundits, to preachers who spoke of God, of salvation, of holiness. The answer, given truthfully, for the young questioner was so sincere, was always, in effect, “No.”

It was during this period of restless search for God that Naren, in November of 1881, first met Sri Ramakrishna in a house of one of the latter’s devotees, Surendra Nath Mitra. The Master, at once attracted to the young man, whose eyes seemed not on this world, and deeply moved by his singing, invited him to visit Dakshineswar.

PROLOGUE

II

The story of Swami Vivekananda’s life cannot be complete without the story of the life of Sri Ramakrishna, for the two lives formed, as it were, one whole. Yet, in this short account, only a little can be told about him. Sri Ramakrishna, born in 1836, is today held by thousands or, more accurately, millions to have been an Incarnation of God who harmonized within himself all the spiritual thought and experience of the world’s past. Living quietly on the bank of the Ganga at the Dakshineswar temple, Sri Ramakrishna remained in an almost continuous state of God-consciousness, sometimes losing himself utterly in the Absolute Brahman, sometimes, in a slightly lower state, communing with the Personal God in one or another of His, or Her, infinite forms, sometimes, again, perceiving this world of multiplicity shot through and through with the unifying substance of Divinity. His power was that which only the Incarnations of God possess—the power of bestowing, by a touch or a glance, the vision of God and of removing by a wish the accumulated burden of karma from the souls of those who approach them. This power of forgiveness and of granting salvation, to speak in Christian terms, was part and parcel of Sri Ramakrishna’s nature. Childlike in the utter purity of his heart, he eagerly gave Godvision to pundit and illiterate peasant alike, granting his tremendous and liberating grace to all who came to him and were ready to receive it. To those who were not ready-—for the sudden inflowing of God’s grace can shatter a small or flawed vessel—he gave the power of self-preparation and the assurance that it would in short time lead to spiritual fruition. The teachings of Sri Ramakrishna, who combined in himself a vast intellect and an unbounded compassion, who was, in fact, cosmic in mind and heart, were unique both in their all-inclusiveness and in their insistence upon the ability of man to know God directly and in this life.

The first part of Sri Ramakrishna’s life was spent in undergoing extreme austerities and engaging in a multiplicity of spiritual practices. There was no religious path which he did not quickly follow to its promised destination and none which he found invalid. Thus he became a living verification of the fact—new to the world—that all religions, if practiced earnestly, lead to the Godhead. He became also an unerring guide, for he was intimately acquainted with the landmarks and pitfalls of each spiritual road, and knowing at a glance the heart and mind of everyone who came to him, he was able to mold and quicken the life of each along the line best suited to his nature.

The last years of Sri Ramakrishna’s life, from the latter part of 1879 to August of 1886, were spent in giving intensive training to a group of close disciples, who were later to become men of extraordinary spirituality and purity, apostles fit to transmit the teachings and power of their Master to the world.

It was around the end of 1881 that Narendra, in company with friends, first visited Dakshineswar and again met the Master. It was a momentous meeting and one that dumbfounded the young seeker of truth, for Sri Ramakrishna, instantly recognizing Naren’s inherent spiritual greatness, spoke to him in ecstatic, reverential terms, as though greeting a beloved, long absent god. Taking him aside, he poured forth his welcome: “Ah! you have come so late! How unkind of you to keep me waiting so long! My ears are almost seared listening to the cheap talk of worldly people. Oh, how I have been yearning to unburden my mind to one who would understand my inmost feelings!” Telling of the incident at a later time, Naren said: “And so he went on raving and weeping. The next moment he stood before me with folded palms and showing me the regard due to a god, said, ‘I know. Lord, you are that ancient Rishi Narayana in the form of Nara [Man] ; you have again incarnated yourself in order to remove the distress of mankind.’

Speechless, Naren regarded Sri Ramakrishna as stark mad. Yet after the Master had extorted from him a promise to return in a few days and had led him back to the group of devotees, there remained no trace of madness in his behavior. He spoke and acted normally; indeed, he radiated a sense of profound peace and spiritual joy. It was then that Naren asked his usual question: “Sir, have you seen God?” The answer was given at once: “Yes, I see Him just as I see you here, only in a much intenser sense. God can be realized ; one can see and talk to Him as I am doing with you.” Naren, deeply impressed, felt that these extraordinary words came from the depths of an inner experience. They were not the words of a madman, nor were they the words of a mere preacher; they were words that rang true and could not be doubted. He saw, moreover, that the holy man’s life of utter renunciation was in perfect consonance with his teachings, that he was truly a great saint to be revered. Yet how to reconcile this with the strange and extravagant greeting he had received? In a state of bafflement and confusion, Naren returned to Calcutta.

He could not erase from his mind, however, the feeling of blessedness that had come over him as he had sat near the Master. Yet, busy with one thing and another, he did not return to Dakshineswar for nearly a month. During his second visit he had an even stranger experience. After greeting him in his room and bidding him sit beside him, Sri Ramakrishna drew near him in an ecstatic mood and placed his right foot on his body. At this touch Naren saw, with eyes open, the walls, the room, the temple garden, the whole world and even himself disappearing into a void. He felt that he was facing death and cried in consternation, “What are you doing to me? I have my parents!”

The Master laughed and touched Naren’s chest, restoring him to his normal mood. “All right, let it rest now,” he said. “Everything will come in time.”

Versed in Western learning and by nature averse to the mysterious, Naren was convinced that Sri Ramakrishna had exerted a hypnotic influence over him. Yet the question remained how a madman could hypnotize so strong a mind as was his. Deeply perplexed, yet deeply attracted, he soon returned for a third visit, determined to hold his own. But this time he fared no better. By a mere touch the Master again caused him to lose all outward consciousness. Referring to this incident, Sri Ramakrishna later said: “I put several questions to him while he was in that state. I asked him about his antecedents and where he lived, his mission in this world and the duration of his mortal life. He dived deep into himself and gave fitting answers to my questions. They only confirmed what I had seen and inferred about him. Those things shall be a secret, but I came to know that he was a sage who had attained perfection, a past master in meditation, and that the day he knew who he really was, he would give up the body, by an act of will, through yoga.”

From first to last, Sri Ramakrishna could not praise Naren highly enough. He had not been speaking rhetorically when he had called him “Lord—the incarnation of Narayana.” His feeling for his young disciple bordered on reverence, so deeply aware was he of Naren’s godlike nature. Again and again he spoke of him in ecstatic terms: “Behold! Here is Naren. See! See! Oh, what power of insight he has! It is like the shoreless sea of radiance! The Mother, Mahamaya, Herself, cannot approach within ten feet of him! ” At another time he said: “He has eighteen extraordinary powers, one or two of which are sufficient to make a man famous in the world.” Again, “He is a blazing, roaring fire consuming all impurities to ashes.”

Through all this, Naren remained dubious, thinking the Master to be blinded by the intensity of his love. His intellect, moreover, and the religious training he had received in the Brahmo Samaj forbade him to accept Sri Ramakrishna’s doctrines —the doctrine, for instance, of monism, which claimed that all was really Brahman, or God. From the point of view of the Brahmo Samaj this was blasphemy. Sri Ramakrishna’s belief in the living existence of innumerable forms of God and in their manifestation in images was equally blasphemous, if not downright superstitious. Even the Master’s visions and superconscious experiences were looked upon by Naren with the eye of the skeptic—not the shallow skeptic who disbelieves merely because he does not understand, but one who insists that truth be known with his whole being before he will accept it as valid. Naren could never abrogate his reason for the sake of finding comfort in an easy faith. Thus for more than four years he fought his Master, torn between the obvious genuineness of Sri Ramakrishna’s sainthood and his own refusal to accept as true anything that his experience did not verify.

Throughout those years Naren visited Dakshineswar often, drawn by his love for his guru. Those days spent at the feet of the Master in company with other disciples were golden ones. Sri Ramakrishna trained his boys with a light though unerringly sure touch. In times of laughter and play, in serious discussion, in moods of spiritual ecstasy, even in the everyday routine of eating and sleeping, he transformed life into a festival. The commonplace became extraordinary, and the slightest happening, a spiritual lesson. In so brief a sketch as this, little justice can be done to Narendra’s discipleship at Dakshineswar, and to the reader who is unfamiliar with the story one can only recommend that he turn to the biographies of Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda, particularly to Sri Ramakrishna the Great Master by Swami Saradananda and the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna by M, for in those books he will find a new and luminous dimension to this world—indeed he will find a new world altogether.

Gradually Narendra’s doubts disappeared. Engaging in arduous spiritual exercises under the careful eye of his guru, he proved by his own experience the truth of many of Sri Ramakrishna’s claims. At the same time his intellect expanded into what might be called, for lack of a better word, “superintellect,” in the light of which many contradictions that had plagued him were resolved and many apparent fallacies were seen as higher truths.

But before Narendra surrendered completely to Sri Ramakrishna he was to undergo a bitter experience. In the early part of 1884 he passed his Bachelor of Arts examinations. Shortly thereafter, while he was spending the evening at the home of a friend, news came of the sudden death of his father from a heart attack. The shock was a severe one, for Naren had been deeply devoted to his father. But the full extent of the loss did not become apparent until several days later, when it was discovered that Vishwanath Datta, who all his life had freely given of his wealth to all who asked, had left his family not only penniless but burdened with debt.

The following months were a nightmare. Naren, whose life had always been one of physical comfort, now found himself without funds and the sole support of his mother, two elder sisters, two younger brothers and sundry relatives. Creditors knocked at the door ; there was seldom enough to eat; clothes became threadbare, and, on top of all, a branch of the Datta family claimed part of the old mansion—the best part—as rightfully theirs. The claim was unfounded, but the case was brought to the law courts, where it dragged on and on. Although it was finally decided in favor of Naren’s family, it created in its course much unpleasantness, publicity and suspense.

In the meantime Naren sought everywhere for work. “Even before the period of mourning was over,” he later told, “I had to knock about in search of a job. Starving and barefooted, I wandered from office to office under the scorching noonday sun with an application in hand, . . . everywhere the door was slammed in my face.” Those who had previously toadied to members of the Datta family now scorned them. As for Narendra’s true friends, few knew the state to which he had been reduced, for out of self-respect he said nothing. At first his faith in God’s mercy remained firm, but soon in the face of the misery of his own family, which made vivid to him the sufferings of helpless millions of his countrymen, his faith turned to doubt.

One evening toward the end of the summer, after the rains had begun, Naren was returning home from a day of fruitless job-hunting. Weak with hunger and unable to take a step farther, he sank down by the roadside. Perhaps he slept for a time; perhaps he only lapsed into a semiconscious state, but suddenly a change began to take place within him. Deep below the surface of his mind he felt that the veils of uncertainty and confusion were being removed one after the other. Theological problems, which were always more to him than mere intellectual puzzles, became automatically solved, and the meaning of the ways of God with man was clearly revealed. He knew also, with a sure knowledge that sprang from the depths of his being, that he must renounce the world.

Sri Ramakrishna, however, aware of all that had taken place within his disciple, asked him not to take up the life of a wandering monk for as long as he himself might live. It was not to be long. But during the year that remained of the life of the Master, Naren, after having provided for his family with the help of a fellow disciple, underwent innumerable spiritual practices. He quickly attained height after height of spiritual experience and reached at last the final goal of all spiritual endeavor: the complete identification of the individual soul with the Absolute Brahman. But he was not destined to remain immersed in that state.

“Now then,” the Master said to him after his attainment of monistic experience, “the Mother has shown you everything. Just as a treasure is locked up in a box, so will this realization you have just had be locked up, and the key shall remain with me. You have work to do. When you will have finished my work, the treasure-box will be unlocked again.”

In the last few days of Sri Ramakrishna’s life he entrusted the care and training of his other disciples—themselves all boys of profound spirituality—to Naren’s hands and imparted to him his final instructions. Then, aware that he was to enter into Mahasamadhi—the last merging into the Absolute from which there is no return to the physical body—and that his days of teaching were over, he transmitted to this greatest of his apostles all the spiritual powers that he had acquired through years of austerity and experience. On August 16, 1886, Sri Ramakrishna passed away.

PROLOGUE

III

The grief of the young disciples, together with the pressure their families exerted upon them to return to their homes and live a “normal” life, might have disbanded them, had it not been for Narendra’s burning enthusiasm and determination to hold them together. Before long, one of Sri Ramakrishna’s householder devotees arranged to support the boys in a place of their own choosing. They chose a dilapidated and reputedly haunted two-story house in Baranagore, midway between Calcutta and Dakshineswar. The young apostles, informally initiated by Sri Ramakrishna into sannyasa, now took formal vows in the presence of one another, and the Sri Ramakrishna Order came into being. The story of Baranagore is the story of fifteen or so young men of total renunciation caught up in a fervor of spiritual longing. In dire poverty but caring nothing for sleep, food or proper clothing, the boys, led by Naren, spent hour upon hour in meditation, worship, study and devotional singing. The spirit of Sri Ramakrishna flowed through them as a constant and sustaining power, and through Naren they seemed again to hear his words and receive his guidance and inspiration.

The traditional ideal of monasticism in India is that of the wandering monk who lives homeless and in complete reliance upon God. The monks of the Baranagore Math were torn between a desire for this life of utter freedom and a desire to hold together as the sons of Sri Ramakrishna. Now and then, one or another would leave the monastery for a month or two. Even Naren, restless for complete independence, made several solitary pilgrimages, only to return, drawn back by his sense of responsibility to his brothers. But in 1888 he decided to break away from Baranagore, not only that his own strength and fearlessness might grow but that his brothers might also learn to stand alone.

The story of the next four years is that of Naren’s solitary wanderings throughout India. Several chapters of the Life of Swami Vivekananda by his Eastern and Western Disciples are devoted to his experiences during that time ; but even so, the story is somewhat disconnected and incomplete, for the Swami rarely spoke in any detail either of his inward spiritual experiences or of his outward trials and triumphs. Suffice it to say that, sometimes living in complete isolation and want, sometimes sharing the meals of humble villagers, sometimes being entertained by rajas and pundits, he strode over the length and breadth of his country, plumbing the life of the people to its depths. At the end of four years he was able to say to his brother monk, Swami Turiyananda, whom he met at Mount Abu, “I don’t know what I have attained spiritually, nor do I care. I know only that my heart has expanded greatly, and I feel that if I could relieve the suffering of one soul by going to hell a hundred times, I would do it.”

At the southernmost tip of India, Cape Comorin, the Swami’s pilgrimage throughout his motherland culminated in a long and deep meditation, during the course of which, according to one of his brother monks to whom he confided the story, he had a profound and revealing spiritual experience. The actual content of this experience we do not know, but the Swami himself has told of his thoughts as he sat on a rock that jutted out into the ocean. He saw, as it were, the whole of India—her past, present and future, her centuries of greatness and also her centuries of degradation. He saw that it was not religion that was the cause of India’s downfall but, on the contrary, the fact that her true religion, the very life and breath of her individuality, was scarcely to be found, and he knew that her only hope was a restatement of the lost spiritual culture of the ancient rishis. His mind encompassing both the roots and the ramifications of India’s problem, and his heart suffering for his country’s downtrodden, poverty-stricken masses, he “hit,” as he later wrote, “upon a plan.”

“We are so many sannyasins wandering about and teaching the people metaphysics—it is all madness. Did not our Gurudeva use to say, ‘An empty stomach is no good for religion’? That those poor people are leading the life of brutes is simply due to ignorance. We have for all ages been sucking their blood and trampling them under foot.

“ . . . Suppose some disinterested sannyasins, bent on doing good to others, go from village to village, disseminating education, and seeking in various ways to better the condition of all down to the Chandala, through oral teaching, and by means of maps, cameras, globes and such other accessories—can’t that bring- forth good in time? All these plans I cannot write out in this short letter. The long and short of it is—if the mountain does not come to Mohammed, Mohammed must go to the mountain. The poor are too poor to come to schools, . . . and they will gain nothing by reading poetry and all that sort of thing. We as a nation have lost our individuality, and that is the cause of all mischief in India. We have to give back to the nation its lost individuality and raise the masses. The Hindu, the Mohammedan, the Christian, all have trampled them under foot. Again the force to raise them must come from inside, that is, from the orthodox Hindus. In every country the evils exist not with, but against religion. Religion therefore is not to blame, but men.

“To effect this, the first thing we need is men, and the next is funds . . . . ”

This was, of course, a revolutionary idea of the function of a sannyasin in India and was to bring about the new type of monasticism that has since been established by the Ramakrishna Math and Mission,

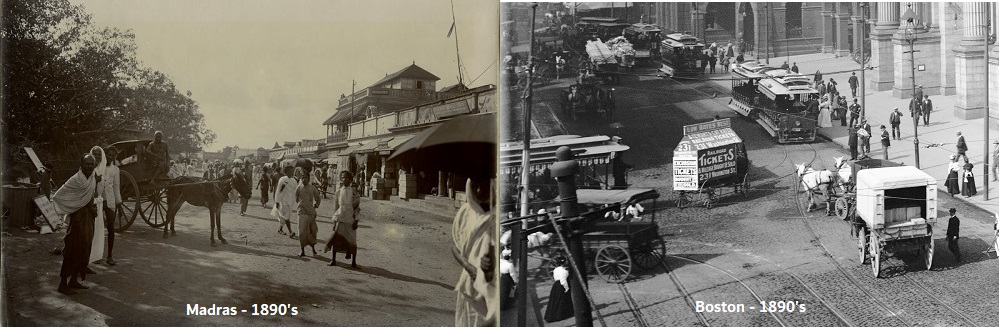

As far as is known, it was in the early part of 1892 that the Swami first heard of the Parliament of Religions, which was to be held in Chicago the following year. His friends and followers urged him to attend it and to represent Hinduism, offering to raise money for his fare and expenses. The Swami himself felt a deep urge to go to America, not so much to represent Hinduism as to obtain financial help and thus put his plan into operation. His final decision to undertake the trip, however, was not made until April of 1893 when, having prayed for guidance, he received, as he later told, “a Divine Command.” Thus assured that the proposed journey was sanctioned by God, Swami Vivekananda, of whom Sri Ramakrishna had once said: “The time will come when he will shake the world to its foundations through the strength of his intellectual and spiritual powers,” left behind all that was dear and familiar to him and, on May 31, 1893, set sail from Bombay for America. After stopping in China and Japan, he re-embarked at Yokohama. As far as can be learned, he crossed the Pacific on the SS. Empress of India, a 6,000-ton ship of the Canadian Pacific Line, which left Yokohama.

On July 14 and landed in Vancouver on the evening of Tuesday, July 25. From Vancouver he went by train to Winnipeg, Canada —the customary route in those days—and from there to Chicago, where, if he made no stopovers on the way, he very likely arrived on the evening of July 30

CHAPTER ONE

BEFORE THE PARLIAMENT

I

Until now, the information we have had regarding the weeks between the midsummer of 1893, when Swami Vivekananda arrived in America, and the opening of the Parliament of Religions in September of the same year, has been scanty and derived largely from one or two letters which he wrote to India. In “The Life of Swami Vivekananda” it is told that when he arrived in Chicago in late July to represent Hinduism at the Parliament of Religions he was not only totally unknown in America and unequipped with any kind of credential, but too late to register as a delegate to the Parliament even if he had credentials. The Parliament of Religions, moreover, was not scheduled to open until September 11. Thus, even to attend it as a spectator Swamiji had several weeks to wait in a strange land where, as he writes in a letter to India, “The expense … is awful.” In order to lessen this expense, he left Chicago for Boston where he had been told the cost of living was lower. “Mysterious,” write his biographers, “are the ways of the Lord! ” ; for it was on the train from Chicago to Boston that Swamiji met “an old lady” who invited him to live at her farm, called “Breezy Meadows,” in Massachusetts. It was through this providential woman, of whom we shall hear more later, that he met Professor John Henry Wright of Harvard. Professor Wright, at once appreciative of Swamiji’s genius, persuaded him, despite his reluctance to return to Chicago because of his meager funds, of the importance of attending the Parliament of Religions. Dr. Wright made all the necessary- arrangements and introduced him as a superbly well-qualified delegate—one who, like the sun, had no need of credentials in order to shine. Indeed, had it not been for Dr. Wright’s insistence and help, it is doubtful that Swamiji would have attended the Parliament.

The little more that has been known regarding the preParliament period of Swamiji’s life has been pieced together from the letter quoted above and dated August 20, 1893. We have known, for instance, that during his stay at “Breezy Meadows” his hostess showed him off as “a curio from India,” that he was gaped at for his “quaint dress,” that he was on this account going to buy Western clothes in Boston, that he was to speak at “a big ladies’ club . . . which is helping Ramabai,” and that he visited and was deeply impressed by a women’s reformatory. To these facts more now can be added, particularly in regard to the period between August 20 and September 8, which until now has been virtually a blank.

Wherever Swamiji went he made news, and in my attempt to fill in the gaps in his life’s story I assumed that New England was no exception to this rule and that the papers of those towns which he visited in the pre-Parliament days would contain some mention of him. The nearest town to the farm “Breezy Meadows” is Metcalf, but upon making inquiries I found that Metcalf was too small to possess a newspaper. The town next in size is Holliston, still not large enough to support a paper of its own, and the next large is Framingham, a full-sized town, complete with newspaper office. It was to Framingham, therefore, that I went. In those days, the Framingham Tribune, which covered the noteworthy events of the surrounding country, was a weekly, coming out on Fridays. There being but few papers to look through, it was not difficult to find the following item which, small as it was and in spite of its quaintness, or perhaps because of it, had the impact of reality:

Friday, August 25, 1893.

Holliston: Miss Kate Sanborn, who has recently returned from the west, last week entertained the Indian Rajah, Swami Vivikananda. Behind a pair of horses furnished by liveryman F. W. Phipps, Miss Sanborn and the Rajah drove through town on Friday en route for Hunnewell’s.

What a sight that must have been! And who could help mistaking the young monk for a rajah as, in robe and turban, he was regally driven through the quiet New England village behind a pair of trotting horses, the mistress of “Breezy Meadows” at his side? This took place on Friday, August 18. On the following Sunday, Swamiji writes to India that he is going to Boston to buy Western clothes. “People gather by hundreds in the streets to see me. So what I want is to dress myself in a long black coat, and keep a red robe and turban to. wear when I lecture.”

From the above news item we learn for the first time that the name of Swamiji’s hostess was Miss Kate Sanborn. Miss Sanborn was, no doubt, taking her “curio from India” on a social call to Hunnewell’s, an estate some ten miles from “Breezy Meadows.” But, as Swamiji writes resignedly, “… all this must be borne.” Indeed, it was through the sociability of Kate Sanborn and her pardonable delight in showing off her “Rajah” that Swamiji met Dr. Wright and subsequently the whole of America. Amiable, prominent and gregarious, Miss Sanborn was precisely the person to act as hostess to Swamiji in those early days, for she not only introduced him to Dr. Wright but was instrumental in providing him with a well-rounded preview of the American scene.

Further research regarding Miss Sanborn revealed that, aside from being an enthusiastic hostess, she was a lecturer and author, taking for her topics all the numerous facets of her active life— people, incidents, places. Although Swamiji referred to her as “an old lady,” she was, by American standards, not old when he first knew her. She was fifty-four and very energetic. She was possessed of a lively humor and a warm feeling for the human show, was keenly observant and widely known for her repartee. Even in her correspondence her wit was bubbling and irrepressible. It was her practice to include in her letters short and apt verses scribbled on cards. One of these, sent to a group of young women, advises: “Though you’re bright/And though you’re pretty/They’ll not love you/If you’re witty.” A more serious and thoughtful side of her nature is revealed by another card which reads: “Down with the fallacy enshrined in Senator Ingalls’ sonnet on the one opportunity. She comes, not alone in the gospel of the ‘second opportunity,’ but she is with you everv day and hour waiting for recognition.”

Originally from New Hampshire, Kate Sanborn had bought one of the old abandoned farms of Massachusetts and had proceeded to restore it into “Breezy Meadows.” Two of her books are devoted to her life on the farm, and it is from these that one learns of the scene that greeted Swamiji. She writes lovingly of the pines and silver birches, the huge elms growing near the house, the natural pond of waterlilies, and the two brooks where forget-me-nots grew along the shaded banks. The house itself was a rambling farmhouse with a vine growing over half the roof. There is a picture of it in one of her books: a friendly, comfortable house. There is also a picture of Kate Sanborn herself (older than when Swamiji knew her) standing in her front doorway offering a welcome to one and all. Today “Breezy Meadows” has changed ; part of the property is occupied by a seminary for Xavierian Fathers, and another part has been given over to a summer camp for Negro children. On this latter part of the farm the house where Swamiji made his first home in America still stands, not much altered, I have been told, by the passage of time.

II

In the letter that Swamiji wrote to India at this time, he mentions, as has already been noted, that he is to speak before a women’s club which was helping Ramabai. Ramabai, of whom we shall hear more in a later chapter, was a Hindu woman who had been converted to Christianity. In 1887-1889 she had been active in forming clubs in America for the purpose of raising funds for Indian child widows, whose plight she had graphically misrepresented. Unfortunately I could find no report in the Boston papers of Swamiji’s talk before the Boston Ramabai Circle. Nor was the 1893 Annual Report of that club more informative. But despite the meagerness of our information, we can at least be sure, in the light of subsequent developments in the Brooklyn Ramabai Circle which will be reported in a later chapter, that Swamiji gave the women of the Boston Ramabai Circle a true picture of India and of child widows and that it was a picture which they did not relish.

The first direct mention of Swamiji in the Boston papers is and philanthropist, extremely active in organizing and promoting works of benevolence. He served as secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Charities—the first of its kind in America— and helped in founding many charitable institutions. He also founded the Concord Summer School of Philosophy and wrote biographies of his friends, Alcott, Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne and others. As will be seen later,’Mr. Sanborn invited Swamiji to speak at a convention of the American Social Science Association in Saratoga Springs, New York—the fashionable resort of the era.

But prior to going to Saratoga Springs, Swamiji passed a busy week and a half in Massachusetts. While he was spending Thursday, August 24, with Mr. Sanborn in Boston, Professor John Henry Wright, anxious to meet the phenomenal Hindu monk, of whom he had no doubt heard a great deal from the Sanborns, was on his way to Boston from Annisquam, a small resort village on the Atlantic seaboard. Through some misadventure, this meeting did not take place. Yet perhaps this was no misadventure at all, but the hand of Providence, for, not to be deprived of meeting Swamiji, Professor Wright invited him to spend the week-end at Annisquam. It was during this week-end that the professor formed the opinion of his guest that was to have such far-reaching consequences. A letter written by Mrs. Wright to her mother, which has recently come to light, tells of the occasion:

Annisquam, Mass.

August 29, 1893

My dear Mother:

We have been having a queer time. Kate Sanborn had a Hindoo monk in tow as I believe I mentioned in my last letter. John went down to meet him in Boston and missing him, invited him up here. He came Friday! In a long saffron robe that caused universal amazement. He was a most gorgeous vision. He had a superb carriage of the head, was very handsome in an oriental way, about thirty years old in time, ages in civilization. He stayed until Monday and was one of the most interesting people I have yet come across. We talked all day all night and began again with interest the next morning. The town was in a fume to see him; the boarders at Miss Lane’s in wild excitement. They were in and out of the Lodge constantly and little Mrs. Merrill’s eyes were blazing and her cheeks red with excitement. Chiefly we talked religion. It was a kind of revival, I have not felt so wrought up for a long time myself! Then on Sunday John had him invited to speak in the church and they took up a collection for a Heathen college to be carried on on strictly heathen principles—whereupon I retired to my corner and laughed until I cried.

He is an educated gentleman, knows as much as anybody. Has been a monk since he was eighteen. Their vows are very much our vows, or rather the vows of a Christian monk. Only Poverty with them means poverty. They have no monastery, no property, they cannot even beg; but they sit and wait until alms are given them. Then they sit and teach people. For days they talk and dispute. He is wonderfully clever and clear in putting his arguments and laying his trains [of thoughts] to a conclusion. You can’t trip him up, nor get ahead of him.

I have a lot of notes I made as stuff for a possible story—at any rate as something very interesting for future reference. We may see hundreds of Hindoo monks in our lives—and we may not.

Aside from its importance in opening Swamiji’s way to the Parliament of Religions, this week-end lastingly enriched the Wright family—as well it might have, for none fortunate enough to have Swamiji as a guest soon forgot him. The memory of this and later meetings—of which there will be more in a following chapter—became a part of the Wright family tradition, and Mr. John Wright, the son of Professor and Mrs. Wright, through whose kindness his mother’s letters and journals have been made available, today still speaks in the family idiom of “Our Swami,” though he was but a child of two when Swamiji first came to Annisquam.

Mrs. Wright did indeed compose a story from her notes, a story which has been found among her papers. In regard to it, Mr. Wright tells us that “sometime in or after 1897, she prepared the account from the original notes, which have disappeared. She either typed it herself or had it typed by a stenographer and then thoroughly revised it in ink.” Mr. Wright’s deduction regarding the date of the manuscript is based on the fact that the typewriter on which it was written did not come into the family until 1897.

When we first received a copy of this manuscript, it seemed both familiar and new, and on comparing it with material in “The Life,” we found, to be sure, that some portions of it had already been published. On pages 416-419 of the fourth edition, readers will find an article which is said to have come from a newspaper and which is a very much abridged version of the same story. Mr. Wright was not aware that his mother had contributed her article to a newspaper, and it is not known where or when it first appeared; but inasmuch as we are now in possession of the complete manuscript, this is of little importance. The unpublished portions comprise a good half of the original article and are, I believe, of absorbing interest, for they give an intimate picture of Swamiji from the pen of one who well understood that her subject was no ordinary person. But perhaps it is a picture that might also prove shocking. Mrs. Wright has caught Swamiji in one of his bursts of fire, hard for some to reconcile with his calm, all-compassionate, all-loving nature. Fire and compassion, however, are not disparate—indeed they often are as inseparable as the two sides of one coin. Swamiji’s heart, one never can forget, was full of unhappiness for the suffering of his motherland, and correspondingly his mind was full of anger against all that contributed to her degradation. In the early days he ascribed a great deal of that degradation to the imperialism of the British, and it was only natural that he would lash out against a people who had ruthlessly crushed those whom he loved. It is well known that when Swamiji later met the English people on their home ground he became an ardent admirer of their many noble characteristics, but nonetheless he never changed his opinion of British imperialism nor, for that matter, of any oppression of one people by another. Swamiji was a thorough student of the jrld’s history, and whenever in the story of man’s life he found justice and inhumanity he never hesitated to point them out :i no uncertain terms.

However, here are the unpublished portions of Mrs. Wright’s article. For the sake of clarity and continuity I have here and there retained portions which have already been quoted in The Life,” and, for the same reason, I have omitted a word or phrase here and there and made a few minor corrections.

According to Mrs. Wright’s story, the Annisquam villagers and the boarders at the Lodge first caught sight of Swamiji as, in company with Professor Wright, he crossed the lawn between the boarding-house and the professor’s cottage. So astonishing a sight did Swamiji present in this quiet little New England village that speculations set in at once as to who this majestic and colorful figure might be. From where had he come? What was his nationality? And so forth. The article continues as follows:

. . . Finally they decided that he was a Brahmin, and the theory was rudely shattered when that night, at supper, they saw him partake, wonderingly, but evidently with relish, of hash.

It was something that needed explanation and they unanimously repaired to the cottage after supper, to hear this strange new being discourse. . . .

“It was the other day,” he said, in his musical voice, “only just the other day—not more than four hundred years ago.” And then followed tales of cruelty and oppression, of a patient race and a suffering people, and of a judgment to come! “Ah, the English,” he said, “only just a little while ago they were savages, . . . the vermin crawled on the ladies’ bodices, . . . and they scented themselves to disguise the abominable odor of their persons. . . . Most hor-r-ible! Even now, they are barely emerging from barbarism.”

“Nonsense,” said one of his scandalized hearers, “that was at least five hundred years ago.”

“And did I not say ‘a little while ago’? What are a few hundred years when you look at the antiquity of the human soul?” Then with a turn of tone, quite reasonable and gentle, “They are quite savage,” he said. “The frightful cold, the want and privation of their northern climate,” going on more quickly and warmly, “has made them wild. They only think to kill. . . . Where is their rel-igion? They take the name of that Holy One, they claim to love their fellowmen, they civilize—by Christianity!—No! It is their hunger that has civilized them, not their God. The love of man is on their lips, in their hearts there is nothing but evil and every violence. ‘I love you my brother, I love you! ’ . . . and all the while they cut his throat I Their hands are red with blood.” . . . Then, going on more slowly, his beautiful voice deepening till it sounded like a bell, “But the judgment of God will fall upon them. ‘Vengeance is mine ; I will repay, saith the Lord,’ and destruction is coming. What are your Christians? Not one third of the world. Look at those Chinese, millions of them. They are the vengeance of God that will light upon you. There will be another invasion of the Huns,” adding, with a little chuckle, “they will sweep over Europe, they will not leave one stone standing upon another. Men, women, children, all will go and the dark ages will come again.” His voice was indescribably sad and pitiful; then suddenly and flippantly, dropping the seer, “Me,— I don’t care! The world will rise up better from it, but it is coming. The vengeance of God, it is coming soon.”

“Soon?” they all asked.

“It will not be a thousand years until it is done.” They drew a breath of relief. It did not seem imminent.

“And God will have vengeance,” he went on. “You may not see it in religion, you may not see it in politics, but you must see it in history, and as it has been ; it will come to pass. If you grind down the people, you will suffer. We in India are suffering the vengeance of God. Look upon these things. They ground down those poor people for their own wealth, they heard not the voice of distress, they ate from gold and silver when the people cried for bread, and the Mohammedans came upon them slaughtering and killing: slaughtering and killing they overran them. India has been conquered again and again for years, and last and worst of all came the Englishman. You look about India, what has the Hindoo left? Wonderful temples, everywhere. What has the Mohammedan left? Beautiful palaces. What has the Englishman left? Nothing but mounds of broken brandy bottles! And God has had no mercy upon my people because they had no mercy. By their cruelty they degraded the populace, and when they needed them the common people had no strength to give for their aid. If man cannot believe in the Vengeance of God, he certainly cannot deny the Vengeance of History. And it will come upon the English ; they have their heels on our necks, they have sucked the last drop of our blood for their own pleasures, they have carried away with them millions of our money, while our people have starved by villages and provinces. And now the Chinaman is the vengeance that will fall upon them ; if the Chinese rose today and swept the English into the sea, as they well deserve, it would be no more than justice.”

And then, having said his say, the Swami was silent. A babble of thin-voiced chatter rose about him, to which he listened, apparently unheeding. Occasionally he cast his eye up to the roof and repeated softly, “Shiva! Shiva! ” and the little company, shaken and disturbed by the current of powerful feelings and vindictive passion which seemed to be flowing like molten lava beneath the silent surface of this strange being, broke up, perturbed

He stayed days [actually it was only a long weekend]. . . . All through, his discourses abounded in picturesque illustrations and beautiful legends. . . .

One beautiful story he told was of a man whose wife reproached him with his troubles, reviled him because of the success of others, and recounted to him all his failures. “Is this what your God has done for you,’’ she said to him, “after you have served Him so many years?” Then the man answered, “Am I a trader in religion? Look at that mountain. What does it do for me, or what have I done for it? And yet I love it because I am so made that I love the beautiful. Thus I love God.” . . . There was another story he told of a king who offered a gift to a Rishi. The Rishi refused, but the king insisted and begged that he would come with him. When they came to the palace he heard the king praying, and the king begged for wealth, for power, for length of days from God. The Rishi listened, wondering, until at last he picked up his mat and started away. Then the king opened his eyes from his prayers and saw him. “Why are you going?” he said. “You have not asked for your gift.” “I,” said the Rishi, “ask from a beggar?”

When someone suggested to him that Christianity was a saving power, he opened his great dark eyes upon him and said, “If Christianity is a saving power in itself, why has it not saved the Ethiopians, the Abyssinians?” He also arraigned our own crimes, the horror of women on the stage, the frightful immorality in our streets, our drunkenness, our thieving, our political degeneracy, the murdering in our West, the lynching in our South, and we, remembering his own Thugs, were still too delicate to mention them. . . .

Often on Swamiji’s lips was the phrase, “They would not dare to do this to a monk.” … At times he even expressed a great longing that the English government would take him and shoot him. “It would be the first nail in their coffin,” he would say, with a little gleam of his white teeth, “and my death would run through the land like wild fire.” . . .

His great heroine was the dreadful [?] Ranee of the Indian mutiny, who led her troops in person. Most of the old mutineers, he said, had become monks in order to hide themselves, and this accounted very well for the dangerous quality of the monks’ opinions. There was one man of them who had lost four sons and could

u speak of them with composure, but whenever he mentioned the Ranee he would weep, with tears streaming down his face. “That woman was a goddess,” he said, “a devi. When overcome, she fell on her sword and died like a man.” It was strange to hear the other side of the Indian mutiny, when you would never believe that there was another side to it, and to be assured that a Hindoo could not possibly kill a woman. It was probably the Mohammedans that killed the women at Delhi and Cawnpore. These old mutineers would say to him, “Kill a woman! You know we could not do that” ; and so the Mohammedan was made responsible.

In quoting from the Upanishads his voice was most musical. He would quote a verse in Sanskrit, with intonations, and then translate it into beautiful English, of which he had a wonderful command. And in his mystical religion he seemed perfectly and unquestionably happy. . . .

It is interesting to compare the prophetic utterances Swamiji made in Annisquam with those reported by Sister Christine in her “Reminiscences”: “Sometimes he was in a prophetic mood, as on the day when he startled us by saying: ‘The next great upheaval which is to bring about a new epoch will come from Russia or China.’ ” And I have been reliably informed that at another time Swamiji made a statement to the effect that if and when the British should leave India there would be a great danger of India’s being conquered by the Chinese. I mention these statements of Swamiji just in passing, and the reader may accept them in whatever spirit he likes.

Although this memorable and, as it turned out, historymaking week-end caused such a stir among the populace in Annisquam, the Gloucester Daily Times, which covered the Annisquam news, ran on August 28 the following item, typical of New England’s verbal economy:

Annisquam.

Mr. Sivanei Yivcksnanda, a Hindoo monk, gave a fine lecture in the church last evening on the customs and life in India.

But although this was all the newspaper had to say about Swamiji’s lecture on August 27, there are even today people to whom its main burden is still fresh and to whom Swamiji is still vivid. One woman, a summer resident of the village, writes to me in regard to Swamiji’s week-end in Annisquam: “I consider it a great privilege to have known him. He was a striking-looking man in appearance and dress. He wore a turban around his head and a long orange robe of heavy woolen [?] cloth with a wide purple sash. He had a charming voice. He began his lecture in the Annisquam village church by saying that the Hindus were taught to have a great respect for other people’s religions.”

On Monday, August 28, Swamiji left Annisquam for Salem, where he was scheduled to speak before the Thought and Work Club. The only information we have hitherto had of this lecture engagement is a bare reference in Swamiji’s “Breezy Meadows” letter. But his stay in Salem was more extended and active than this brief reference indicates. Recently we have been fortunate enough to find out more about it. The steps leading to this discovery are perhaps of interest.

More:

‘I have a message to the West as Buddha had a message to the East.”

Swami Vivekananda

“Swami, brooding alone and in silence on that point of rock off the tip of India, the vision came; there flashed before his mind the new continent of America, a land of optimism, great wealth, and unstinted generosity. He saw America as a country of unlimited opportunities, where people’s minds were free from the encumbrance of

castes or classes. He would give the receptive Americans the ancient wisdom of India

and bring back to his motherland, in exchange, the knowledge of science and

technology. If he succeeded in his mission to America, he would not only enhance

India’s prestige in the Occident, but create a new confidence among his own people. He

recalled the earnest requests of his friends to represent India in the forthcoming

Parliament of Religions in Chicago. And in particular, he remembered the words of the

friends in Kathiawar who had been the first to encourage him to go to the West: ‘Go

and take it by storm, and then return!'” – Swami Vivekananda – A Biography by Swami Nikhilananda

Swami Vivekananda had first heard about the Parliament of Religions towards the end of 1891 or 1892 while traveling through India. His friends and followers urged him to attend it and to represent Hinduism, offering to raise money for his fare and expenses.