‘I have a message to the West as Buddha had a message to the East.”

Swami Vivekananda

“Swami, brooding alone and in silence on that point of rock off the tip of India, the vision came; there flashed before his mind the new continent of America, a land of optimism, great wealth, and unstinted generosity. He saw America as a country of unlimited opportunities, where people’s minds were free from the encumbrance of

castes or classes. He would give the receptive Americans the ancient wisdom of India

and bring back to his motherland, in exchange, the knowledge of science and

technology. If he succeeded in his mission to America, he would not only enhance

India’s prestige in the Occident, but create a new confidence among his own people. He

recalled the earnest requests of his friends to represent India in the forthcoming

Parliament of Religions in Chicago. And in particular, he remembered the words of the

friends in Kathiawar who had been the first to encourage him to go to the West: ‘Go

and take it by storm, and then return!'” – Swami Vivekananda – A Biography by Swami Nikhilananda

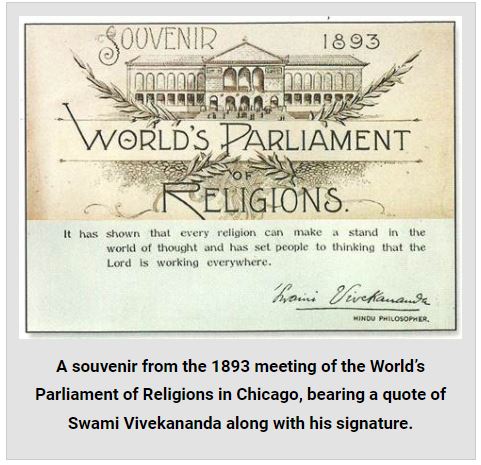

Swami Vivekananda had first heard about the Parliament of Religions towards the end of 1891 or 1892 while traveling through India. His friends and followers urged him to attend it and to represent Hinduism, offering to raise money for his fare and expenses.

Maharaja Ajit Singh Bahadur, the ruler of the Shekhawat dynasty of the princely state of Khetri in Rajputana and Narendra Dutta (Vivekananda), a monk who went by the name of Swami Bibidishanand. Narendra, a bhakt of Sri Ramakrishna) become a close friend and a staunch disciple, Ajit Singh was also the person to whom Narendra turned for help whenever the need arose. Letters written by Swami Vivekanand mention his plans and difficulties, clearly showing his dependence and faith in his friend. In a letter to Ajit Singh dated November 22, 1898, Vivekananda writes, “I have not the least shame in opening my mind to you and that I consider you as my only friend in this life”.

Maharaja Ajit Singh Bahadur, the ruler of the Shekhawat dynasty of the princely state of Khetri in Rajputana and Narendra Dutta (Vivekananda), a monk who went by the name of Swami Bibidishanand. Narendra, a bhakt of Sri Ramakrishna) become a close friend and a staunch disciple, Ajit Singh was also the person to whom Narendra turned for help whenever the need arose. Letters written by Swami Vivekanand mention his plans and difficulties, clearly showing his dependence and faith in his friend. In a letter to Ajit Singh dated November 22, 1898, Vivekananda writes, “I have not the least shame in opening my mind to you and that I consider you as my only friend in this life”.

Ajit Singh persuaded and provided financial help so that his friend Narendra could attend and participate in the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago in 1893. Narendra left Bombay for Chicago on May 31, 1893, with a new name suggested by his friend. Henceforth, he would be known as “Vivekananda”! It was indeed a perfect name for Narendra — Vivekananda meant “the bliss of discerning wisdom” — in Sanskrit it is a combination of viveka (wisdom) and ananda (bliss).

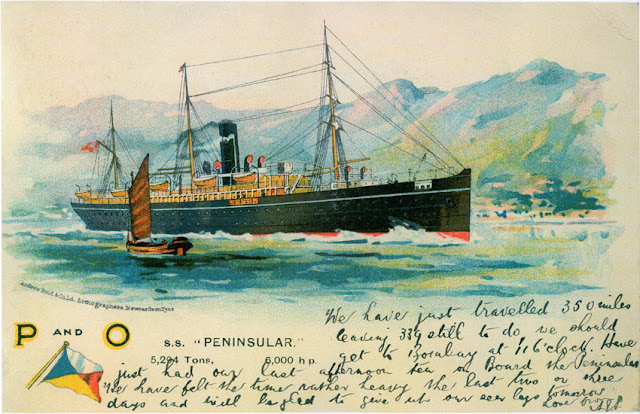

His final decision to undertake the trip, however, was not made until April of 1893 when, having prayed for guidance, he received, as he later told, “a Divine Command.” On May 31, 1893, he set sail from Bombay for America aboard the SS. Peninsular.

Setting sail, May 1893

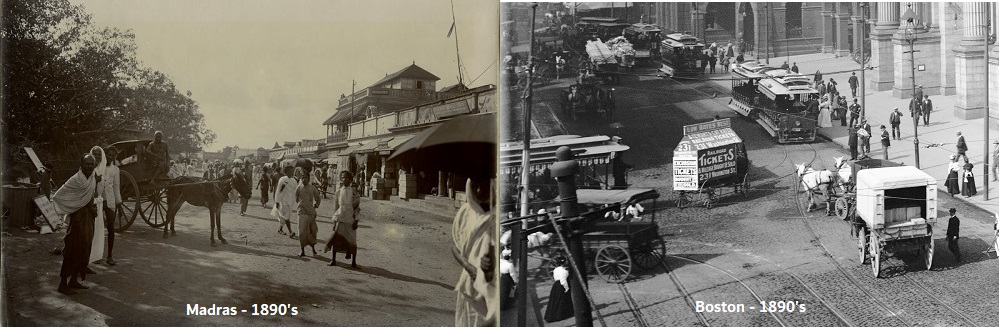

The transmission of ideas across the British Empire wasn’t all one way. By the end of the century, there was increasing interest in Eastern spiritual ideas in the West.

Vivekananda got a call to go to America when he heard that there a World’s Parliament of Religions was being held in Chicago. When he was asked why he was going to America,

Swamiji expressed his pain and said:

”I have traveled all over India. But alas, it was agony to me, my brothers, to see with my own eyes the terrible poverty and misery of the masses, and I could not restrain my tears. It is now my firm conviction that it is futile to preach religion amongst them without first trying to remove their poverty and their suffering. It is for this reason – to find more means for the salvation of the poor in India – that I am now going to America.”

Vivekananda must have been aware of this when he resolved to travel to America in order to raise funds for his new social project: “As our country is poor in social virtues, so this country is lacking spirituality. I give them spirituality and they give me money,” he reasoned.

In May 1893 he boarded a steamship at the east coast port of Bombay, bound for North America. But instead of traveling West, he traveled East – first to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), then via Singapore to Hong Kong and China, and finally to Japan.

Along the way, he discovered Sanskrit manuscripts at Buddhist temples in China and Japan and was struck by the influence of Buddhist and Hindu spirituality across Asia. Perhaps these encounters confirmed his belief in the international appeal of Indian spirituality.

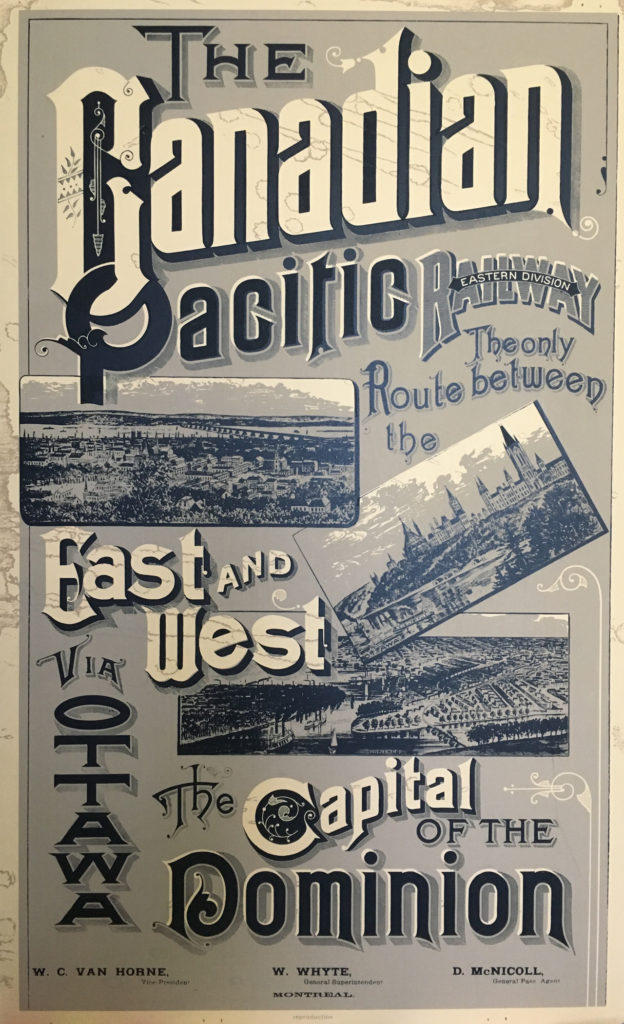

From Yokahama, he sailed across the Pacific to Vancouver and then took a train across Canada, arriving in Chicago at the end of July.

Traveling by train, The Canadian Pacific, to Chicago on his way to speak at the Parliament of Religions.

With funds collected by his Madras disciples, the kings of Mysore, Ramnad, Khetri, diwans and other followers, Narendra left Bombay for Chicago on 31 May 1893 with the name “Vivekananda” which was suggested by Ajit Singh of Khetri. The name “Vivekananda” meant “the bliss of discerning wisdom”.

Vivekananda began his journey to America from Bombay, India on 31 May 1893, on the ship named peninsula[4] His journey to America took him to China, Japan and Canada. At Canton (Guangzhou) he saw some Buddhist monasteries. Then he visited Japan. First he went to Nagasaki. He saw three more big cities and then reached Osaka, Kyoto and Tokyo, and then he reached Yokohama. He started his journey to Canada in a ship named RMS Empress of India from Yokohama.

In the journey from Yokohama to Canada on the ship Empress, Vivekananda accidentally met Jamsetji Tata who was also going to Chicago. Tata, a businessman who made his initial fortune in the opium trade with China and started one of the first textile mills in India, was going to Chicago to get new business ideas. In this accidental meeting on the Empress, Vivekananda inspired Tata to set up a research and educational institution in India. They also discussed a plan to start a steel factory in India.

He reached Vancouver on 25 July. From Vancouver (of Canada) he traveled to Chicago by train and arrived there on Sunday, 30 July 1893.

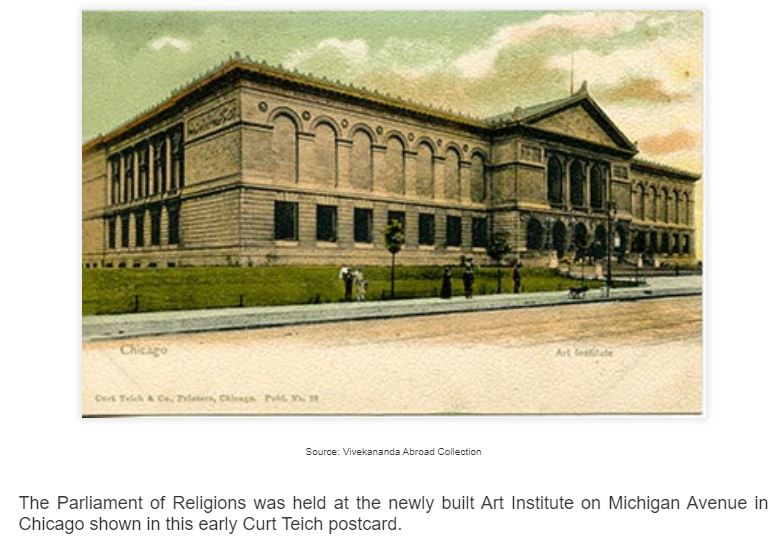

After reaching Chicago, Vivekananda learned no one could attend the Parliament as delegate without credential or bona fide. He did not have one at that moment and felt utterly disappointed. He also learned the Parliament would not open till first week of September.

He arrived in Vancouver on July 25. From there, he took the Canadian Pacific Railway train and arrived at Chicago on July 30th.

The World’s Columbian Exposition had been underway for three months when he arrived and to his shock found that the authorities of the Parliament of Religions required all delegates to produce credentials. Moreover, he was, he found, too late to register as a delegate even if he had had credentials. Thus his hope of speaking before the Parliament vanished almost at once and there remained no chance of his gaining a hearing in America until the late fall when the “lecture season” would begin. The cost of living in Chicago being exorbitant, he decided to go to Boston.

During the twelve days or so that Swamiji spent in Chicago, he visited the Fair almost every day, for it was a huge and spectacular exhibition of the modern wonders of steam and electricity, and, as he wrote, “one must take at least ten days to go through it.”. Thus it was in something like despair that he left Chicago for Boston, where, as he had been told, the cost of living was lower.

Going to Boston

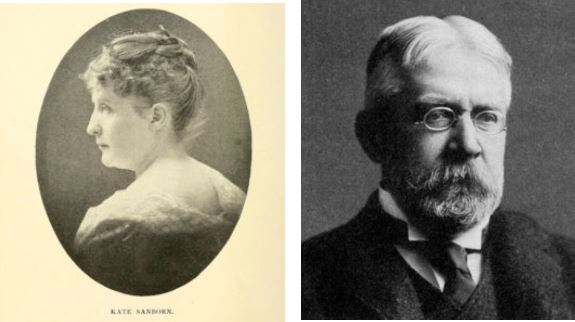

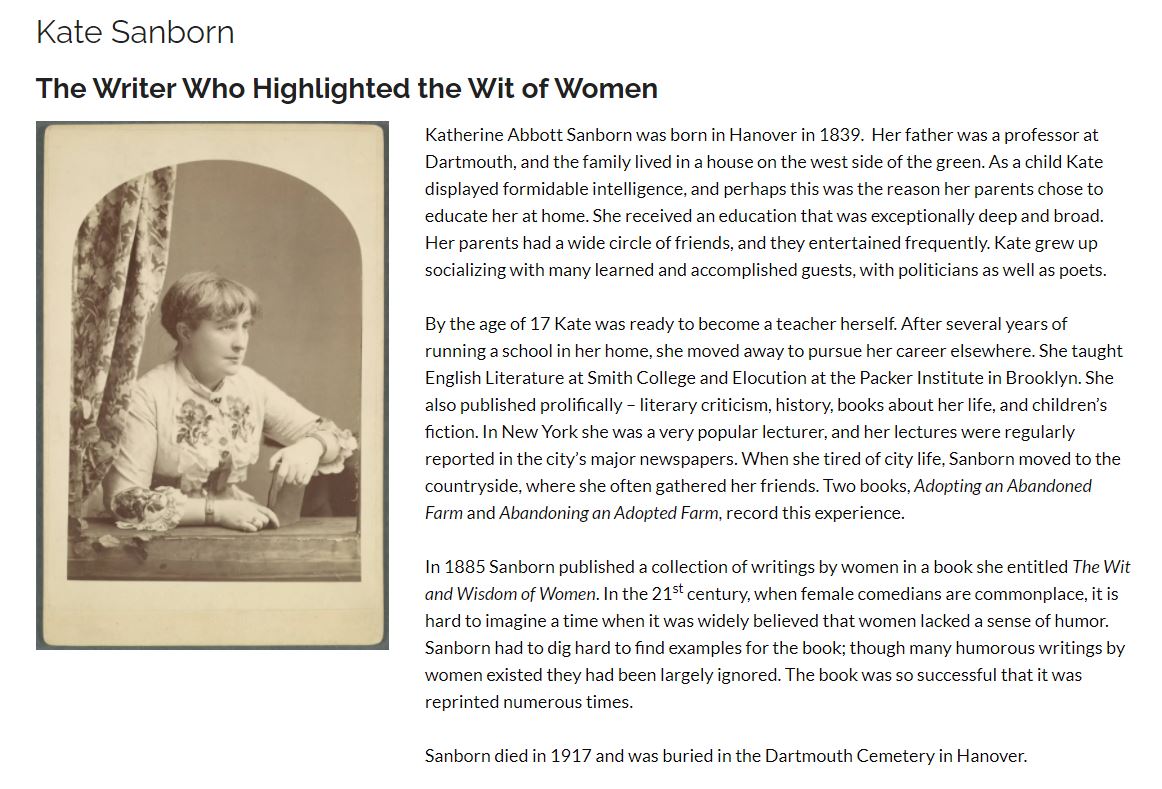

On the train, he met Miss Kate Sanborn, who invited him to be a guest at her home.

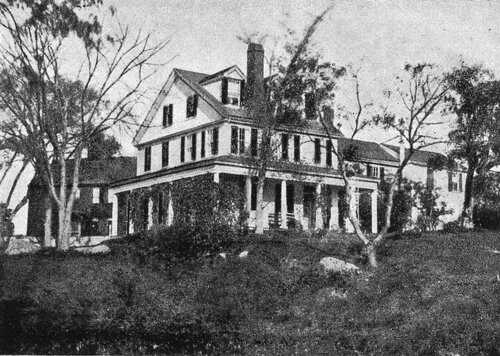

It was at her estate, In Framington, Massachusetts called Breezy Meadows, that Swami Vivekananda was introduced to a number of Bostonians, including Harvard Classics professor John Henry Wright.

Meeting with John Henry Wright

“To ask for your credentials is like asking the sun to state its right to shine in the heavens.”

At Boston, Vivekananda met Professor John Henry Wright of Harvard University. Professor Wright invited Vivekananda to give a lecture at the University. After being acquainted with Vivekananda’s knowledge, wisdom and excellence, Professor Wright insisted him to represent Hinduism at the Parliament of World’s Religions.[9] Vivekananda himself later wrote– “He urged upon me the necessity of going to the Parliament of Religions, which he thought would give an introduction to the nation”. When Wright learned that Vivekananda was not officially accredited and did not have any credential to join the Parliament, he told Vivekananda– “To ask for your credentials is like asking the sun to state its right to shine in the heavens.”

Professor Wright was at once appreciative of Swamiji’s genius and persuaded him of the importance of attending the Parliament of Religions. He gave him all the necessary assistance; he introduced him by letter to all the proper authorities as a superbly well-qualified delegate, one “who is more learned than all our learned professors put together” and who, as he said, was like the sun, with no need of credentials in order to shine; he brought his train ticket back to Chicago, gave him some money, and saw to it that his housing would be arranged for.

***

Brahmin Monk in Framingham

(Arizona Rebublican August 30, 1893)

SOUTH FRAMINGHAM, Aug. 20.1893

The Swami Vivekananda of India, a Brahmin monk who is on his way to the parliament of religions to be held at Chicago in September, was a guest today at the reformatory prison for women. Early this evening he addressed the inmates of the institution in the chapel upon the manners, customs, and mode of living in his country.

The gentleman, who is of rare intellectual ability and learning, was much interested

in the workings of the reformatory and expressed himself as highly pleased with what he saw.

He returned this evening to Metcalf, where he is the guest of Miss Kate Sanborn at her abandoned farm.

***

The most vivid and enduring literary portrait of Swami Vivekananda during his first days in North America was penned by writer Katherine Abbot Sanborn. They were passengers on the Canadian Pacific Railway heading east from Vancouver across the magnificent Canadian Rockies.

Miss Sanborn had been doing a lecture tour in California, promoting her latest book, ‘A Truthful Woman In Southern California’.

Kate Sanborn’s eyewitness account of Swami Vivekananda in the CPR observation car is really important to the story of his journey across North America. Kate Sanborn was building a national reputation as a witty writer. In 1891 she wrote a very popular book, Adopting an Abandoned Farm and its 1894 sequel Abandoning an Adopted Farm contained this portrait of Swamiji:

“I had met him in the the observation car of the Canadian Pacific where even the gigantically grand scenery of mountains, canyons, glaciers, and the Great Divide could not take my eyes entirely from the cosmopolitan travelers, all en route for Chicago. Parsees from India, Canton Merchant millionaires, New Zealanders, pretty women from Phillipine Isles married to Portuguese and Spanish traders, Japanese dignitaries with their cultivated wives and collegiate sons, high bred and well informed, etc.

I talked with all. They cordially invited me to visit them at their respective homes, and I, nothing abashed, spoke in rather glowing terms of my rural residence, and gave each my card, with “Metcalf, Mass.,” as permanent address. I alluded to the distinguished men and women in Boston and vicinity who were frequently my guests, and assured all of a hearty welcome at my farm.

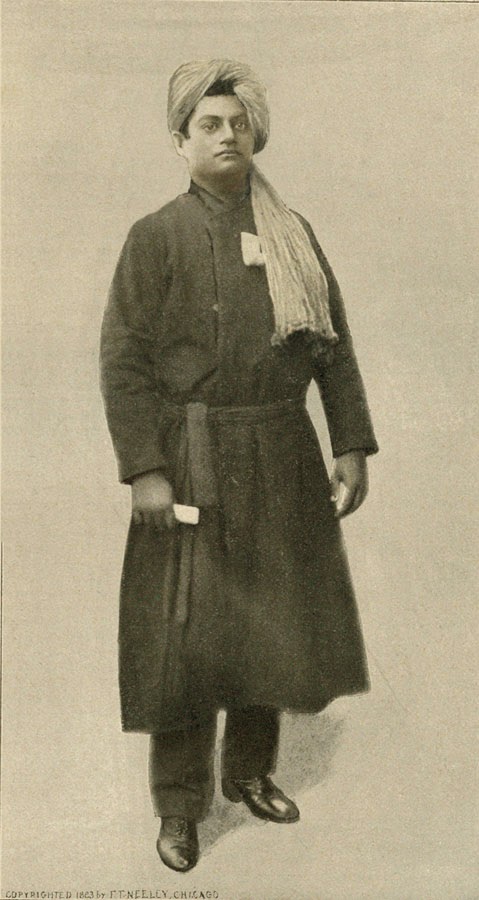

But most of all was I impressed by the monk, a magnificent specimen of manhood—six feet two, as handsome as Salvini at his best, with a lordly, imposing stride, as if he ruled the universe, and soft, dark eyes that could flash fire if roused or dance with merriment if the conversation amused him. He wore a bright yellow turban many yards in length, a red ochre robe, the badge of his calling; this was tied with a pink sash, broad and heavily be fringed. Snuff-brown trousers and russet shoes completed the outfit.

He spoke better English than I did, was conversant with ancient and modern literature, would quote easily and naturally from Shakespeare or Longfellow or Tennyson, Darwin, Miiller, Tyndall; could repeat pages of our Bible, was familiar with and tolerant of all creeds. He was an education, an illumination, a revelation! I told him, as we separated, I should be most pleased to present him to some men and women of learning and general culture, if by any chance he should come to Boston.”

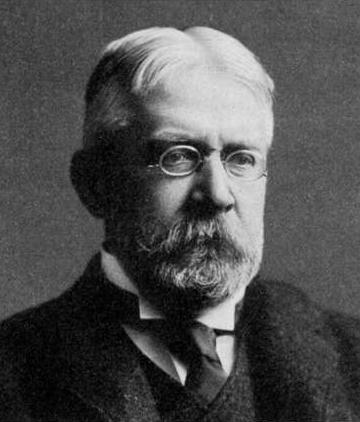

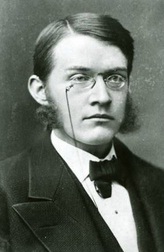

John Henry Wright, a Greek professor at Harvard

Swami Vivekananda spent several days in Holliston, as the guest of Kate Sanborn. Ms. Sanborn introduced him to many influential people including John Henry Wright, a professor at Harvard University. Prof. Wright was vacationing with his family in Annisquam at the time, and he invited the Swami to join them for the weekend.

Many also know of Prof Wright’s contribution in getting Swamiji an opportunity to attend and present his thoughts at the World Parliament of Religion but very few people know of Swami Vivekananda’s first public discourse in the United States of America.

John Henry Wright helped Vivekananda make the arrangements for his Parliament appearance; and then he stayed at the Annisquam residence of Alpheus Hyatt, whose marine biology station on Lobster Cove was the first iteration of the present-day Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute.

Professor John Henry Wright, anxious to meet the phenomenal Hindu monk, of whom he had no doubt heard a great deal from the Sanborns, was on his way to Boston from Annisquam, a small resort village on the Atlantic seaboard.

Swami Vivekananda and Annisquam

Professor Wright invited him to spend the weekend at Annisquam. It was during this weekend that the professor formed the opinion of his guest that was to have such far-reaching consequences.

A letter written by Mrs, Wright to her mother, which has recently come to light, tells of the occasion:

Annisquam, Mass. August 29,1893

My dear Mother:

We have been having a queer lime. Kate Sanborn had a Hindoo monk in tow as I believe I mentioned in my last letter. John went down to meet him in Boston and missing him, invited him up here. He came Friday! In a long safTron robe that caused universal amazement. He was a most gorgeous vision. He had a superb carriage of the head, was very handsome in an oriental way, about thirty years old in lime, ages in civilization. He stayed until Monday and was one of the most in-teresting people I have yet come across.

We talked all day all night and began again with interest the next morning. The town was in a fume to see him; the boarders at MroriLine’s in wild excitement. They were in and out of the Lodge constantly and little Mrs. Merrill’s eyes were blazing and her cheeks red with excitement. Chiefly we talked religion. It was a kind of revival, I have not felt so wrought up for a long time myself! Then on Sunday John had him invited to speak in the church and they took up a collection for a Heathen college to be carried on on strictly heathen principles – whereupon I retired to my corner and laughed until I cried.

He is an educated gentleman, knows as much as anybody. Has been a monk since he was eighteen. Their vows are very much our vows, or rather the vows of a Christian monk. Only Poverty with them means poverty. They have no monastery, no property, they cannot even beg; but they sit and wait until alms are given them. Then they sit and teach people. For days they talk and dispute. He is wonderfully clever and clear in putting his arguments and laying his trains [of thoughts] to a conclusion. You can’t trip him up, nor get ahead of him.

I have a lot of notes I made as stuff for a possible story – at any rate as something very interesting for future reference. We may see hundreds of Hindoo monks in our lives – and we may not.

It was August 25th, 1893 and many professors, artists, clergymen, and writers from Boston and other cities including Chicago had come to a quiet village called Annisquam on the Massachusetts coast.

They were assembling in one of the village’s largest boarding houses called Miss Lane’s Boarding House which had many spacious rooms and a large dining room. People here were coming at the invitation of Professor John Henry Wright of Harvard University.

“It was in this quiet village, Annisquam, from where ships had sailed to China and India before revolutionary times that another revolution was so quietly begun.”

The talk given by Swami Vivekananda at the Parliament of Religions in Chicago in September 1893 is now part of history.

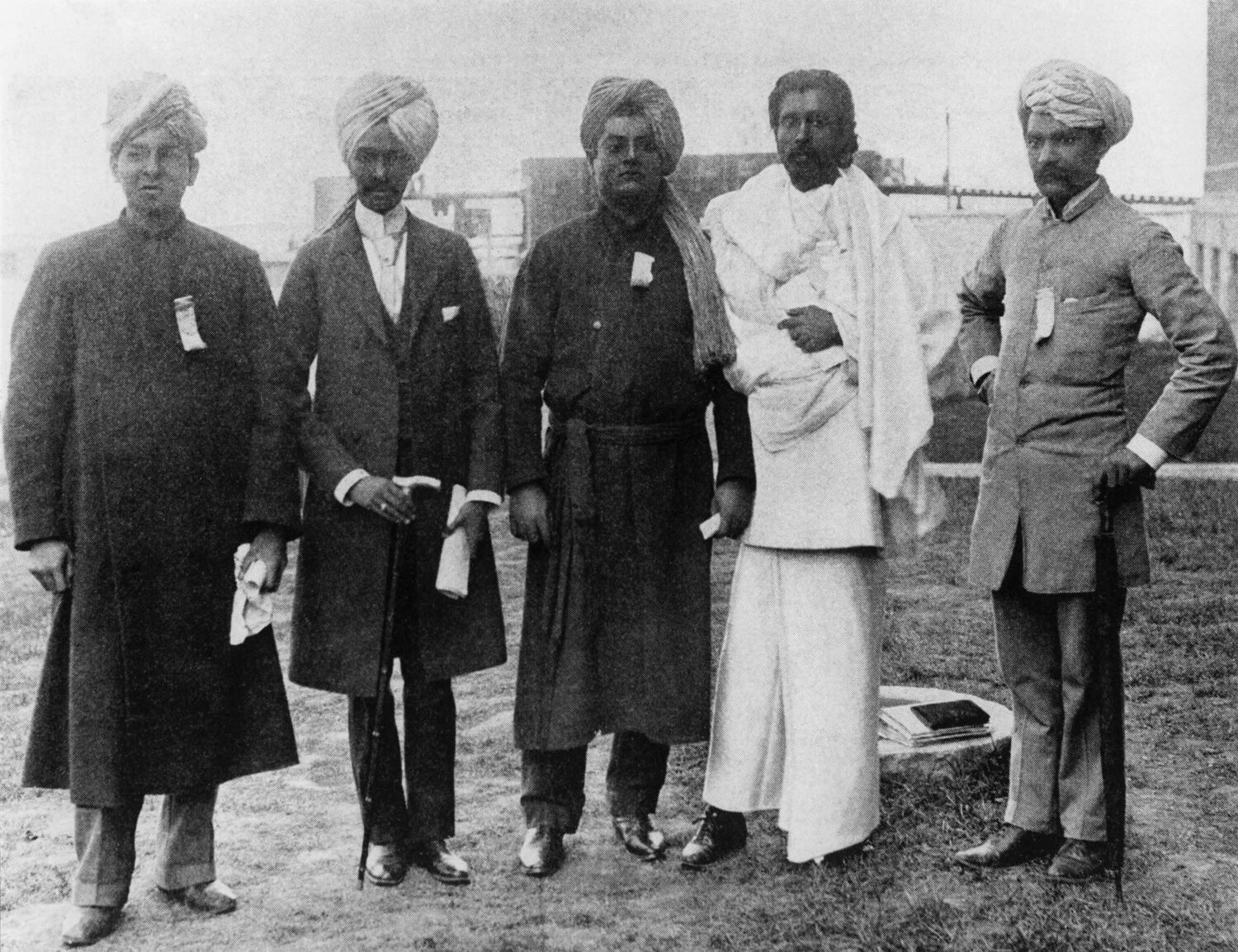

The “East Indian Group” at the Parliament of the World’s Religions. From left to right are Narasima Charya, Lakshmi Narain, Swami Vivekananda, Hewivitarne Dharmapala, and Virachand Raghav Gandhi.

Most Indians relate Swamiji to this talk and historians agree that it was possibly a key milestone in introducing Swami Vivekananda to the world stage. Many also know of Prof Wright’s contribution in getting Swamiji an opportunity to attend and present his thoughts at this Parliament.

But very few people know of Swami Vivekananda’s first public discourse in the United States of America. It was August 25th, 1893 and many professors, artists, clergymen and writers from Boston and other cities including Chicago had come to a quite village called Annisquam on the Massachusetts coast.

They were assembling in one of the village’s largest boarding houses called Miss Lane’s Boarding House which had many spacious rooms and a large dining room. People here were coming at the invitation of Professor John Henry Wright of Harvard University. Prof Wright had mentioned that he would be coming with a young Hindu monk whom he had recently met. He knew that he was in the presence of a force, the dimensions of which he could barely fathom but which had captivated him. The melodious voice, the leonine bearing, the spiritual glow in the great dark eyes of this young man of twenty-nine attracted all who approached him and when he spoke, there was a strange and compelling reverberation felt within all who heard him.

Mrs Wright recording this visit to Annisquam wrote, “He walked with a strange, shambling gait, and yet there was a commanding dignity and impressiveness in the carriage of his neck and bare head that caused everyone in sight to stop and look at him; he moved slowly with the swinging tread of one who has never hastened, and in his great dark eyes was the beauty of an alien civilization…”

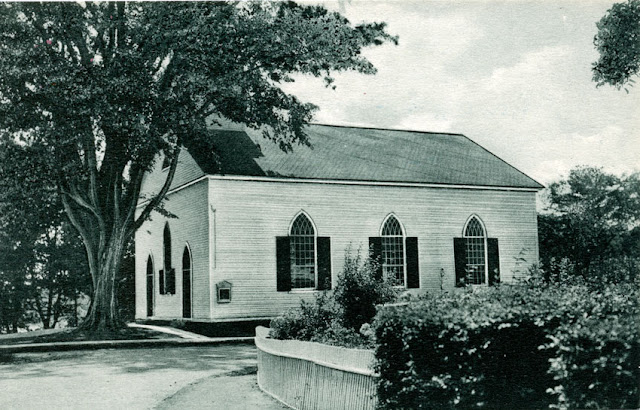

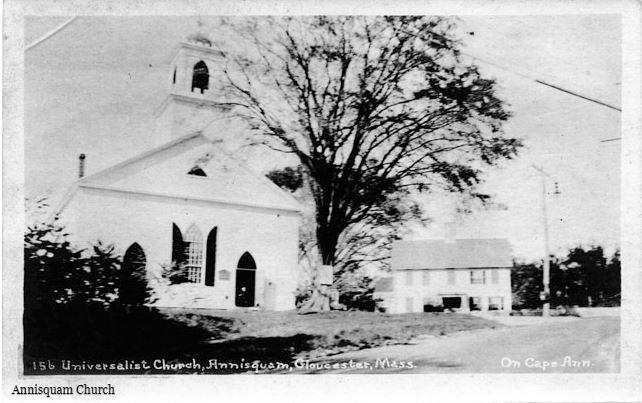

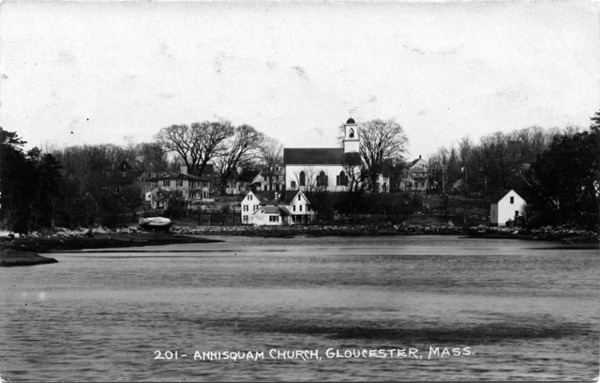

Annisquam Church

On that chilly Sunday, the Hindu monk was asked to speak at the Annisquam Universalist Church at the invitation of its pastor, Rev G W Penniman. Elva Nelson who researched this visit of Swami Vivekananda had this to say of his first public discourse in America. “It marked the beginning of his unprecedented work in the West. It was in this quiet village, Annisquam, from where ships had sailed to China and India before revolutionary times that another revolution was so quietly begun.”

This first talk given on that Sunday in a little church was to mark the beginning of Swami Vivekananda’s work in the West. This heralded the approach of a spiritual storm which spread across the entire country.

Prof Wright had mentioned that he would be coming with a young Hindu monk whom he had recently met.

He knew that he was in the presence of a force, the dimensions of which he could barely fathom but which had captivated him. The melodious voice, the leonine bearing, the spiritual glow in the great dark eyes of this young man of twenty-nine attracted all who approached him and when he spoke, there was a strange and compelling reverberation felt within all who heard him. Mrs Wright recording this visit to Annisquam wrote, “He walked with a strange, shambling gait, and yet there was a commanding dignity and impressiveness in the carriage of his neck and bare head that caused everyone in sight to stop and look at him; he moved slowly with the swinging tread of one who has never hastened, and in his great dark eyes was the beauty of an alien civilization…”

On that chilly Sunday, the Hindu monk was asked to speak at the Annisquam Universalist Church at the invitation of its pastor, Rev G W Penniman. Elva Nelson who researched this visit of Swami Vivekananda had this to say of his first public discourse in America. “It marked the beginning of his unprecedented work in the West. It was in this quiet village, Annisquam, from where ships had sailed to China and India before revolutionary times that another revolution was so quietly begun.” This first talk given on that Sunday in a little church was to mark the beginning of Swami Vivekananda’s work in the West.

Mary Tappan Letter about Swami Vivekananda

Mary Tappan Wright was the wife of Harvard Professor of Greek, John Henry Wright and a novelist in 1900’s wrote a letter to her mother about Swami Vivekananda.

“It is not an exaggeration to say Swami Vivekananda conquered the United States spiritually. He taught spiritual things to the Foreigners while back home he wanted young males to stop reading sacred texts and sacrifice for the country by doing work. He is one of the best role models for the youth, even today.”

In a letter to her mother, she writes:

August 29, 1893

Annisquam, Mass.

My dear Mother:

We have been having a queer time. Kate Sanborn had a Hindoo monk in tow, as I believe I mentioned in my last letter. John went down to meet him in Boston and missing him, invited him up here. He came Friday in a long saffron robe that caused universal amazement. He was a most gorgeous vision. He had a superb carriage of the head, was very handsome in an oriental way, about thirty years old in time, ages in civilization. He stayed until Monday and was one of the most interesting people I have yet come across. We talked all day all night and began again with interest the next morning. The town was in a fume to see him; the boarders at Miss Lane’s in wild excitement. They were in and out of the Lodge (the Wright’s cottage] constantly and little Mrs. Merrill’s eyes were blazing and her cheeks red with excitement. Chiefly we talked religion. It was a kind of revival; I have not felt so wrought up for a long time myself! Then on Sunday John had him invited to speak in the church and they took up a collection for a Heathen college to be carried on strictly heathen principles-whereupon I retired to my corner and laughed until I cried.

He is an educated gentleman, knows as much as anybody. Has been a monk since he was eighteen. Their vows are very much our vows, or rather the vows of a Christian monk. Only Poverty with them means poverty. They have no monastery, no property, they cannot even beg; but they sit and wait until alms are given them. Then they sit and teach people. For days they talk and dispute. He is wonderfully clever and clear in putting his arguments and laying his trains (of thought) to a conclusion. You can’t trip him up, nor get ahead of him. I have a lot of notes I made as stuff for a possible story -at any rate as something very interesting for future reference. We may see hundreds of Hindoo monks in our lives-and we may not.

Annisquam

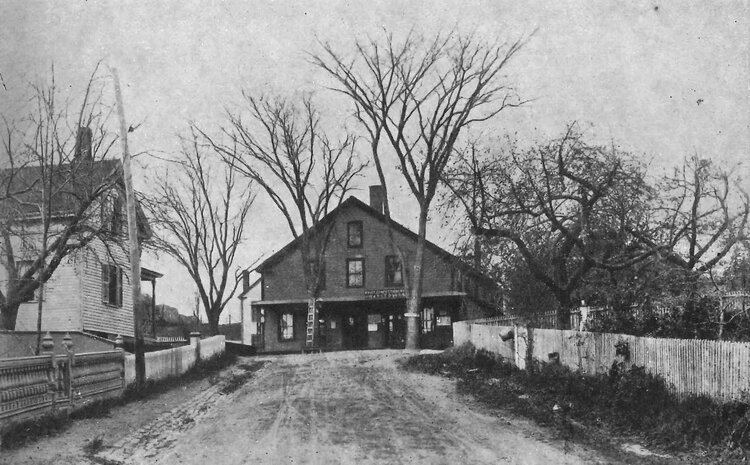

MISS LANE’S BOARDING HOUSE (8 ARLINGTON ST)

August 25–28, 1893

Prof. Wright rented a room for Swami Vivekananda at Miss Lane’s Boarding House near his small summer cottage, called The Lodge, adjacent to Miss Lane’s. (The boarding house is now a private residence.) The boarders at Miss Lane’s were all excited to see this exotic visitor from a far off land. The meeting with Swamiji and Prof. Wright turned out to be extremely significant, since Prof. Wright was so impressed with Swamiji that he wrote a letter of recommendation for him to the Parliament of Religions, commenting that Swamiji was “more learned than all our learned professors put together.”

Most of Swamiji’s weekend was spent informally with the Wright family. On 25th evening Swamiji gave an informal talk at the home of Prof. Wambaugh of Harvard University Law School, who was staying only two houses from Miss Lane’s. The following evening, on 26th, Swamiji visited the home of Prof. Alpheus Hyatt, who was a zoologist. When Swamiji returned to Annisquam the following summer, he stayed at Prof. Hyatt’s house.

Much of what is known about his 1893 visit to Annisquam comes from Prof. Wright’s wife’s diary. She wrote in her diary that Swamiji played with her children, “twirling a stick between his fingers with laughing skill and glee at their inability to equal him.” He was, she wrote, “wonderfully unspoiled and simple.” She concluded an entry with this vignette of Swamiji’s parlor talks: “In quoting from the Upanishads his voice was most musical. He would quote a a verse in Sanskrit, with intonations, and then translate it into beautiful English, of which he had a wonderful command. And in his mystical religion he seemed perfectly and unquestionably happy.”

Swamiji’s first ever public lecture in the West was given here at the Universalist Church (now known as the Annisquam Village Church) on Sunday evening on “The Manners and Customs of India.” The stained glass window behind the altar had not been installed yet in Swamiji’s time. The existing building was built in 1810, but the church was founded over a century earlier.

On Monday, Aug 29, Swamiji left Annisquam for Salem, Massachusetts. He returned to Annisquam for another visit the following summer, in 1894.

On July 28, 2013, a plaque was installed inside the church to mark Swamiji’s visit there 130 years earlier. The event was celebrated with music, talks, a play presented by the village children, a tour of the village, and refreshments.

Swami Vivekananda stayed as Mrs. Frances Newbury Bagley’s guest in 1894 at The Hyatt House, a private residence in a section of Annisquam called Goose Cove. It is about a half mile walk from Annisquam Village via the footbridge over Lobster Cove. Or one can stop to see it from the causeway on Washington Street while driving from Annisquam to Magnolia.

The house is on the waterfront and rather secluded. During his stay, Swamiji joined in swimming and boating excursions, and learned about Victorian era American culture.

Mrs. Bagley of Detroit had rented the house of Prof. Alpheus Hyatt for the summer. Mrs. Bagley was one of the organizers of the Chicago World’s Fair, and had met Swamiji while he was there for the Parliament of Religions. She was the widow of Mr. John Judson Bagley, a businessman who made his fortune in tobacco and also served as the governor of Michigan from 1873-77. Mrs. Bagley hosted Swamiji during his visits to Detroit in February and March of 1894.

MECHANICS HALL (36 LEONARD ST)

September 4, 1894

View fullsizeMechanics Hall (Archival)

Mechanics Hall (Archival)

View fullsize(2009)

(2009)

Before departing, Swamiji delivered a lecture: “Life and Religion in India” on September 4 in Mechanics Hall, a small hall in the center of Annisquam village. It occupied the second floor of the Annisquam Village Hall. Centrally located, it was the place in the village for almost all functions. On that spot today are businesses and a small library. The Annisquam Historical Society is next door.

When Swamiji spoke at the Mechanics Hall, the hall was full. He was introduced to the audience by Prof. Wright, who was staying at Miss Lane’s that summer with his family. Swamiji’s visit was covered by both the Cape Ann Breeze as well as the Gloucester Daily Times.

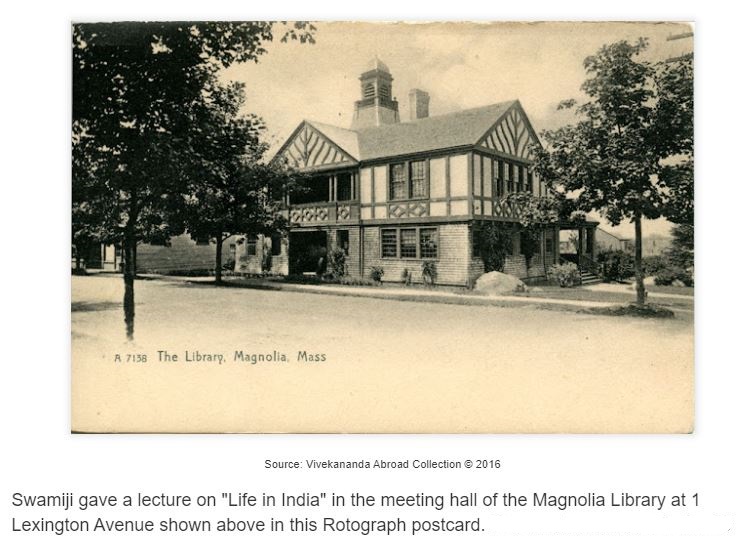

Magnolia (Aug 24-26, 1894)

During his 1894 visit to Annisquam, Swamiji made a side trip to Magnolia, another district of Gloucester. He was invited there by a lady from Chicago and her daughter, Mrs. Smith and Mrs. Sawyer. They also arranged a lecture for him at the Magnolia Library (CW, 9. 35).

MAGNOLIA LIBRARY (1 LEXINGTON AVE)

August 24, 1894

Swamiji spoke in the Library Hall on “Life in India” on Friday the 24th. The hall is on the second floor of the Magnolia Library.

MAGNOLIA BEACH

Swamiji went swimming at the beach here, as we learn from a letter he wrote from Magnolia to Mrs. Hale of Chicago. In his letter Swamiji wrote, “Magnolia is one of the most fashionable and beautiful seaside resorts of this part. I think the scenery is better than that of Annisquam. The rocks there are very beautiful, and the forests run down to the very edge of the water. There is a very beautiful pine forest.” Swamiji also said that Magnolia was a good bathing place and that he had “two baths in the sea.” (CW 9. 36)

Vivekananda’s Return to Chicago

When he got back to Chicago, to his horror Vivekananda found he’d lost the addresses of his contacts. Alone, ignored and not knowing where to go, he spent the night in a boxcar and the next morning, forgetting he wasn’t in India any more, ventured out to knock on doors and beg for breakfast. Just imagine the reaction of the average Chicagoan, circa 1893, who opened the front door to a dark-skinned, unshaven stranger wearing a rumpled orange bathrobe and yellow towel wrapped around his head. After being repeatedly turned away, hungry and tired, Vivekananda decided to take the only reasonable course of action: he sat down on the street curb and resigned himself to God’s will. Within minutes God responded in the person of a Mrs George Hale–Kate Sanborn’s fairy godmother successor–whose upscale home was just across the street from Vivekananda’s curb. Chancing to look out a window, Mrs Hale perspicaciously surmised, based on his out-of-the-ordinary attire, that he was a Parliament delegate. She thereupon offered her help and in a trice, Vivekananda was cleaned up, fed, and introduced to the Hales’ good friend, Presbyterian minister John Barrows, who was the chairman of, yes, the World’s Parliament of Religion.

And so through a seemingly miraculous chain of events, self-proclaimed Swami Vivekananda had his ticket to the Parliament.

“He is a blazing, roaring fire consuming all impurities to ashes.”

Ramakrishna speaking of Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda in America – New Discoveries

by Marie Louise Burke

I have a message to the West as Buddha had a message to the East

Swami Vivekananda

1958

1958

As far as is known, it was in the early part of 1892 that the Swami first heard of the Parliament of Religions, which was to be held in Chicago the following year. His friends and followers urged him to attend it and to represent Hinduism, offering to raise money for his fare and expenses. The Swami himself felt a deep urge to go to America, not so much to represent Hinduism as to obtain financial help and thus put his plan into operation. His final decision to undertake the trip, however, was not made until April of 1893 when, having prayed for guidance, he received, as he later told, “a Divine Command.” Thus assured that the proposed journey was sanctioned by God, Swami Vivekananda, of whom Sri Ramakrishna had once said: “The time will come when he will shake the world to its foundations through the strength of his intellectual and spiritual powers,” left behind all that was dear and familiar to him and, on May 31, 1893, set sail from Bombay for America. After stopping in China and Japan, he re-embarked at Yokohama. As far as can be learned, he crossed the Pacific on the SS. Empress of India, a 6,000-ton ship of the Canadian Pacific Line, which left Yokohama.

On July 14 and landed in Vancouver on the evening of Tuesday, July 25. From Vancouver he went by train to Winnipeg, Canada —the customary route in those days—and from there to Chicago, where, if he made no stopovers on the way, he very likely arrived on the evening of July 30

CHAPTER ONE

BEFORE THE PARLIAMENT

I

Until now, the information we have had regarding the weeks between the midsummer of 1893, when Swami Vivekananda arrived in America, and the opening of the Parliament of Religions in September of the same year, has been scanty and derived largely from one or two letters which he wrote to India. In “The Life of Swami Vivekananda” it is told that when he arrived in Chicago in late July to represent Hinduism at the Parliament of Religions he was not only totally unknown in America and unequipped with any kind of credential, but too late to register as a delegate to the Parliament even if he had credentials. The Parliament of Religions, moreover, was not scheduled to open until September 11. Thus, even to attend it as a spectator Swamiji had several weeks to wait in a strange land where, as he writes in a letter to India, “The expense … is awful.” In order to lessen this expense, he left Chicago for Boston where he had been told the cost of living was lower. “Mysterious,” write his biographers, “are the ways of the Lord! ” ; for it was on the train from Chicago to Boston that Swamiji met “an old lady” who invited him to live at her farm, called “Breezy Meadows,” in Massachusetts. It was through this providential woman, of whom we shall hear more later, that he met Professor John Henry Wright of Harvard. Professor Wright, at once appreciative of Swamiji’s genius, persuaded him, despite his reluctance to return to Chicago because of his meager funds, of the importance of attending the Parliament of Religions. Dr. Wright made all the necessary- arrangements and introduced him as a superbly well-qualified delegate—one who, like the sun, had no need of credentials in order to shine. Indeed, had it not been for Dr. Wright’s insistence and help, it is doubtful that Swamiji would have attended the Parliament.

The little more that has been known regarding the preParliament period of Swamiji’s life has been pieced together from the letter quoted above and dated August 20, 1893. We have known, for instance, that during his stay at “Breezy Meadows” his hostess showed him off as “a curio from India,” that he was gaped at for his “quaint dress,” that he was on this account going to buy Western clothes in Boston, that he was to speak at “a big ladies’ club . . . which is helping Ramabai,” and that he visited and was deeply impressed by a women’s reformatory. To these facts more now can be added, particularly in regard to the period between August 20 and September 8, which until now has been virtually a blank.

Wherever Swamiji went he made news, and in my attempt to fill in the gaps in his life’s story I assumed that New England was no exception to this rule and that the papers of those towns which he visited in the pre-Parliament days would contain some mention of him. The nearest town to the farm “Breezy Meadows” is Metcalf, but upon making inquiries I found that Metcalf was too small to possess a newspaper. The town next in size is Holliston, still not large enough to support a paper of its own, and the next large is Framingham, a full-sized town, complete with newspaper office. It was to Framingham, therefore, that I went. In those days, the Framingham Tribune, which covered the noteworthy events of the surrounding country, was a weekly, coming out on Fridays. There being but few papers to look through, it was not difficult to find the following item which, small as it was and in spite of its quaintness, or perhaps because of it, had the impact of reality:

Friday, August 25, 1893.

Holliston: Miss Kate Sanborn, who has recently returned from the west, last week entertained the Indian Rajah, Swami Vivikananda. Behind a pair of horses furnished by liveryman F. W. Phipps, Miss Sanborn and the Rajah drove through town on Friday en route for Hunnewell’s.

What a sight that must have been! And who could help mistaking the young monk for a rajah as, in robe and turban, he was regally driven through the quiet New England village behind a pair of trotting horses, the mistress of “Breezy Meadows” at his side? This took place on Friday, August 18. On the following Sunday, Swamiji writes to India that he is going to Boston to buy Western clothes. “People gather by hundreds in the streets to see me. So what I want is to dress myself in a long black coat, and keep a red robe and turban to. wear when I lecture.”

From the above news item we learn for the first time that the name of Swamiji’s hostess was Miss Kate Sanborn. Miss Sanborn was, no doubt, taking her “curio from India” on a social call to Hunnewell’s, an estate some ten miles from “Breezy Meadows.” But, as Swamiji writes resignedly, “… all this must be borne.” Indeed, it was through the sociability of Kate Sanborn and her pardonable delight in showing off her “Rajah” that Swamiji met Dr. Wright and subsequently the whole of America. Amiable, prominent and gregarious, Miss Sanborn was precisely the person to act as hostess to Swamiji in those early days, for she not only introduced him to Dr. Wright but was instrumental in providing him with a well-rounded preview of the American scene.

Further research regarding Miss Sanborn revealed that, aside from being an enthusiastic hostess, she was a lecturer and author, taking for her topics all the numerous facets of her active life— people, incidents, places. Although Swamiji referred to her as “an old lady,” she was, by American standards, not old when he first knew her. She was fifty-four and very energetic. She was possessed of a lively humor and a warm feeling for the human show, was keenly observant and widely known for her repartee. Even in her correspondence her wit was bubbling and irrepressible. It was her practice to include in her letters short and apt verses scribbled on cards. One of these, sent to a group of young women, advises: “Though you’re bright/And though you’re pretty/They’ll not love you/If you’re witty.” A more serious and thoughtful side of her nature is revealed by another card which reads: “Down with the fallacy enshrined in Senator Ingalls’ sonnet on the one opportunity. She comes, not alone in the gospel of the ‘second opportunity,’ but she is with you everv day and hour waiting for recognition.”

Originally from New Hampshire, Kate Sanborn had bought one of the old abandoned farms of Massachusetts and had proceeded to restore it into “Breezy Meadows.” Two of her books are devoted to her life on the farm, and it is from these that one learns of the scene that greeted Swamiji. She writes lovingly of the pines and silver birches, the huge elms growing near the house, the natural pond of waterlilies, and the two brooks where forget-me-nots grew along the shaded banks. The house itself was a rambling farmhouse with a vine growing over half the roof. There is a picture of it in one of her books: a friendly, comfortable house. There is also a picture of Kate Sanborn herself (older than when Swamiji knew her) standing in her front doorway offering a welcome to one and all. Today “Breezy Meadows” has changed ; part of the property is occupied by a seminary for Xavierian Fathers, and another part has been given over to a summer camp for Negro children. On this latter part of the farm the house where Swamiji made his first home in America still stands, not much altered, I have been told, by the passage of time.

II

In the letter that Swamiji wrote to India at this time, he mentions, as has already been noted, that he is to speak before a women’s club which was helping Ramabai. Ramabai, of whom we shall hear more in a later chapter, was a Hindu woman who had been converted to Christianity. In 1887-1889 she had been active in forming clubs in America for the purpose of raising funds for Indian child widows, whose plight she had graphically misrepresented. Unfortunately I could find no report in the Boston papers of Swamiji’s talk before the Boston Ramabai Circle. Nor was the 1893 Annual Report of that club more informative. But despite the meagerness of our information, we can at least be sure, in the light of subsequent developments in the Brooklyn Ramabai Circle which will be reported in a later chapter, that Swamiji gave the women of the Boston Ramabai Circle a true picture of India and of child widows and that it was a picture which they did not relish.

The first direct mention of Swamiji in the Boston papers is and philanthropist, extremely active in organizing and promoting works of benevolence. He served as secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Charities—the first of its kind in America— and helped in founding many charitable institutions. He also founded the Concord Summer School of Philosophy and wrote biographies of his friends, Alcott, Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne and others. As will be seen later,’Mr. Sanborn invited Swamiji to speak at a convention of the American Social Science Association in Saratoga Springs, New York—the fashionable resort of the era.

But prior to going to Saratoga Springs, Swamiji passed a busy week and a half in Massachusetts. While he was spending Thursday, August 24, with Mr. Sanborn in Boston, Professor John Henry Wright, anxious to meet the phenomenal Hindu monk, of whom he had no doubt heard a great deal from the Sanborns, was on his way to Boston from Annisquam, a small resort village on the Atlantic seaboard. Through some misadventure, this meeting did not take place. Yet perhaps this was no misadventure at all, but the hand of Providence, for, not to be deprived of meeting Swamiji, Professor Wright invited him to spend the week-end at Annisquam. It was during this week-end that the professor formed the opinion of his guest that was to have such far-reaching consequences. A letter written by Mrs. Wright to her mother, which has recently come to light, tells of the occasion:

Annisquam, Mass.

August 29, 1893

My dear Mother:

We have been having a queer time. Kate Sanborn had a Hindoo monk in tow as I believe I mentioned in my last letter. John went down to meet him in Boston and missing him, invited him up here. He came Friday! In a long saffron robe that caused universal amazement. He was a most gorgeous vision. He had a superb carriage of the head, was very handsome in an oriental way, about thirty years old in time, ages in civilization. He stayed until Monday and was one of the most interesting people I have yet come across. We talked all day all night and began again with interest the next morning. The town was in a fume to see him; the boarders at Miss Lane’s in wild excitement. They were in and out of the Lodge constantly and little Mrs. Merrill’s eyes were blazing and her cheeks red with excitement. Chiefly we talked religion. It was a kind of revival, I have not felt so wrought up for a long time myself! Then on Sunday John had him invited to speak in the church and they took up a collection for a Heathen college to be carried on on strictly heathen principles—whereupon I retired to my corner and laughed until I cried.

He is an educated gentleman, knows as much as anybody. Has been a monk since he was eighteen. Their vows are very much our vows, or rather the vows of a Christian monk. Only Poverty with them means poverty. They have no monastery, no property, they cannot even beg; but they sit and wait until alms are given them. Then they sit and teach people. For days they talk and dispute. He is wonderfully clever and clear in putting his arguments and laying his trains [of thoughts] to a conclusion. You can’t trip him up, nor get ahead of him.

I have a lot of notes I made as stuff for a possible story—at any rate as something very interesting for future reference. We may see hundreds of Hindoo monks in our lives—and we may not.

Aside from its importance in opening Swamiji’s way to the Parliament of Religions, this week-end lastingly enriched the Wright family—as well it might have, for none fortunate enough to have Swamiji as a guest soon forgot him. The memory of this and later meetings—of which there will be more in a following chapter—became a part of the Wright family tradition, and Mr. John Wright, the son of Professor and Mrs. Wright, through whose kindness his mother’s letters and journals have been made available, today still speaks in the family idiom of “Our Swami,” though he was but a child of two when Swamiji first came to Annisquam.

Mrs. Wright did indeed compose a story from her notes, a story which has been found among her papers. In regard to it, Mr. Wright tells us that “sometime in or after 1897, she prepared the account from the original notes, which have disappeared. She either typed it herself or had it typed by a stenographer and then thoroughly revised it in ink.” Mr. Wright’s deduction regarding the date of the manuscript is based on the fact that the typewriter on which it was written did not come into the family until 1897.

When we first received a copy of this manuscript, it seemed both familiar and new, and on comparing it with material in “The Life,” we found, to be sure, that some portions of it had already been published. On pages 416-419 of the fourth edition, readers will find an article which is said to have come from a newspaper and which is a very much abridged version of the same story. Mr. Wright was not aware that his mother had contributed her article to a newspaper, and it is not known where or when it first appeared; but inasmuch as we are now in possession of the complete manuscript, this is of little importance. The unpublished portions comprise a good half of the original article and are, I believe, of absorbing interest, for they give an intimate picture of Swamiji from the pen of one who well understood that her subject was no ordinary person. But perhaps it is a picture that might also prove shocking. Mrs. Wright has caught Swamiji in one of his bursts of fire, hard for some to reconcile with his calm, all-compassionate, all-loving nature. Fire and compassion, however, are not disparate—indeed they often are as inseparable as the two sides of one coin. Swamiji’s heart, one never can forget, was full of unhappiness for the suffering of his motherland, and correspondingly his mind was full of anger against all that contributed to her degradation. In the early days he ascribed a great deal of that degradation to the imperialism of the British, and it was only natural that he would lash out against a people who had ruthlessly crushed those whom he loved. It is well known that when Swamiji later met the English people on their home ground he became an ardent admirer of their many noble characteristics, but nonetheless he never changed his opinion of British imperialism nor, for that matter, of any oppression of one people by another. Swamiji was a thorough student of the jrld’s history, and whenever in the story of man’s life he found justice and inhumanity he never hesitated to point them out :i no uncertain terms.

However, here are the unpublished portions of Mrs. Wright’s article. For the sake of clarity and continuity I have here and there retained portions which have already been quoted in The Life,” and, for the same reason, I have omitted a word or phrase here and there and made a few minor corrections.

According to Mrs. Wright’s story, the Annisquam villagers and the boarders at the Lodge first caught sight of Swamiji as, in company with Professor Wright, he crossed the lawn between the boarding-house and the professor’s cottage. So astonishing a sight did Swamiji present in this quiet little New England village that speculations set in at once as to who this majestic and colorful figure might be. From where had he come? What was his nationality? And so forth. The article continues as follows:

. . . Finally they decided that he was a Brahmin, and the theory was rudely shattered when that night, at supper, they saw him partake, wonderingly, but evidently with relish, of hash.

It was something that needed explanation and they unanimously repaired to the cottage after supper, to hear this strange new being discourse. . . .

“It was the other day,” he said, in his musical voice, “only just the other day—not more than four hundred years ago.” And then followed tales of cruelty and oppression, of a patient race and a suffering people, and of a judgment to come! “Ah, the English,” he said, “only just a little while ago they were savages, . . . the vermin crawled on the ladies’ bodices, . . . and they scented themselves to disguise the abominable odor of their persons. . . . Most hor-r-ible! Even now, they are barely emerging from barbarism.”

“Nonsense,” said one of his scandalized hearers, “that was at least five hundred years ago.”

“And did I not say ‘a little while ago’? What are a few hundred years when you look at the antiquity of the human soul?” Then with a turn of tone, quite reasonable and gentle, “They are quite savage,” he said. “The frightful cold, the want and privation of their northern climate,” going on more quickly and warmly, “has made them wild. They only think to kill. . . . Where is their rel-igion? They take the name of that Holy One, they claim to love their fellowmen, they civilize—by Christianity!—No! It is their hunger that has civilized them, not their God. The love of man is on their lips, in their hearts there is nothing but evil and every violence. ‘I love you my brother, I love you! ’ . . . and all the while they cut his throat I Their hands are red with blood.” . . . Then, going on more slowly, his beautiful voice deepening till it sounded like a bell, “But the judgment of God will fall upon them. ‘Vengeance is mine ; I will repay, saith the Lord,’ and destruction is coming. What are your Christians? Not one third of the world. Look at those Chinese, millions of them. They are the vengeance of God that will light upon you. There will be another invasion of the Huns,” adding, with a little chuckle, “they will sweep over Europe, they will not leave one stone standing upon another. Men, women, children, all will go and the dark ages will come again.” His voice was indescribably sad and pitiful; then suddenly and flippantly, dropping the seer, “Me,— I don’t care! The world will rise up better from it, but it is coming. The vengeance of God, it is coming soon.”

“Soon?” they all asked.

“It will not be a thousand years until it is done.” They drew a breath of relief. It did not seem imminent.

“And God will have vengeance,” he went on. “You may not see it in religion, you may not see it in politics, but you must see it in history, and as it has been ; it will come to pass. If you grind down the people, you will suffer. We in India are suffering the vengeance of God. Look upon these things. They ground down those poor people for their own wealth, they heard not the voice of distress, they ate from gold and silver when the people cried for bread, and the Mohammedans came upon them slaughtering and killing: slaughtering and killing they overran them. India has been conquered again and again for years, and last and worst of all came the Englishman. You look about India, what has the Hindoo left? Wonderful temples, everywhere. What has the Mohammedan left? Beautiful palaces. What has the Englishman left? Nothing but mounds of broken brandy bottles! And God has had no mercy upon my people because they had no mercy. By their cruelty they degraded the populace, and when they needed them the common people had no strength to give for their aid. If man cannot believe in the Vengeance of God, he certainly cannot deny the Vengeance of History. And it will come upon the English ; they have their heels on our necks, they have sucked the last drop of our blood for their own pleasures, they have carried away with them millions of our money, while our people have starved by villages and provinces. And now the Chinaman is the vengeance that will fall upon them ; if the Chinese rose today and swept the English into the sea, as they well deserve, it would be no more than justice.”

And then, having said his say, the Swami was silent. A babble of thin-voiced chatter rose about him, to which he listened, apparently unheeding. Occasionally he cast his eye up to the roof and repeated softly, “Shiva! Shiva! ” and the little company, shaken and disturbed by the current of powerful feelings and vindictive passion which seemed to be flowing like molten lava beneath the silent surface of this strange being, broke up, perturbed

He stayed days [actually it was only a long weekend]. . . . All through, his discourses abounded in picturesque illustrations and beautiful legends. . . .

One beautiful story he told was of a man whose wife reproached him with his troubles, reviled him because of the success of others, and recounted to him all his failures. “Is this what your God has done for you,’’ she said to him, “after you have served Him so many years?” Then the man answered, “Am I a trader in religion? Look at that mountain. What does it do for me, or what have I done for it? And yet I love it because I am so made that I love the beautiful. Thus I love God.” . . . There was another story he told of a king who offered a gift to a Rishi. The Rishi refused, but the king insisted and begged that he would come with him. When they came to the palace he heard the king praying, and the king begged for wealth, for power, for length of days from God. The Rishi listened, wondering, until at last he picked up his mat and started away. Then the king opened his eyes from his prayers and saw him. “Why are you going?” he said. “You have not asked for your gift.” “I,” said the Rishi, “ask from a beggar?”

When someone suggested to him that Christianity was a saving power, he opened his great dark eyes upon him and said, “If Christianity is a saving power in itself, why has it not saved the Ethiopians, the Abyssinians?” He also arraigned our own crimes, the horror of women on the stage, the frightful immorality in our streets, our drunkenness, our thieving, our political degeneracy, the murdering in our West, the lynching in our South, and we, remembering his own Thugs, were still too delicate to mention them. . . .

Often on Swamiji’s lips was the phrase, “They would not dare to do this to a monk.” … At times he even expressed a great longing that the English government would take him and shoot him. “It would be the first nail in their coffin,” he would say, with a little gleam of his white teeth, “and my death would run through the land like wild fire.” . . .

His great heroine was the dreadful [?] Ranee of the Indian mutiny, who led her troops in person. Most of the old mutineers, he said, had become monks in order to hide themselves, and this accounted very well for the dangerous quality of the monks’ opinions. There was one man of them who had lost four sons and could

u speak of them with composure, but whenever he mentioned the Ranee he would weep, with tears streaming down his face. “That woman was a goddess,” he said, “a devi. When overcome, she fell on her sword and died like a man.” It was strange to hear the other side of the Indian mutiny, when you would never believe that there was another side to it, and to be assured that a Hindoo could not possibly kill a woman. It was probably the Mohammedans that killed the women at Delhi and Cawnpore. These old mutineers would say to him, “Kill a woman! You know we could not do that” ; and so the Mohammedan was made responsible.

In quoting from the Upanishads his voice was most musical. He would quote a verse in Sanskrit, with intonations, and then translate it into beautiful English, of which he had a wonderful command. And in his mystical religion he seemed perfectly and unquestionably happy. . . .

It is interesting to compare the prophetic utterances Swamiji made in Annisquam with those reported by Sister Christine in her “Reminiscences”: “Sometimes he was in a prophetic mood, as on the day when he startled us by saying: ‘The next great upheaval which is to bring about a new epoch will come from Russia or China.’ ” And I have been reliably informed that at another time Swamiji made a statement to the effect that if and when the British should leave India there would be a great danger of India’s being conquered by the Chinese. I mention these statements of Swamiji just in passing, and the reader may accept them in whatever spirit he likes.

Although this memorable and, as it turned out, historymaking week-end caused such a stir among the populace in Annisquam, the Gloucester Daily Times, which covered the Annisquam news, ran on August 28 the following item, typical of New England’s verbal economy:

Annisquam.

Mr. Sivanei Yivcksnanda, a Hindoo monk, gave a fine lecture in the church last evening on the customs and life in India.

But although this was all the newspaper had to say about Swamiji’s lecture on August 27, there are even today people to whom its main burden is still fresh and to whom Swamiji is still vivid. One woman, a summer resident of the village, writes to me in regard to Swamiji’s week-end in Annisquam: “I consider it a great privilege to have known him. He was a striking-looking man in appearance and dress. He wore a turban around his head and a long orange robe of heavy woolen [?] cloth with a wide purple sash. He had a charming voice. He began his lecture in the Annisquam village church by saying that the Hindus were taught to have a great respect for other people’s religions.”

On Monday, August 28, Swamiji left Annisquam for Salem, where he was scheduled to speak before the Thought and Work Club. The only information we have hitherto had of this lecture engagement is a bare reference in Swamiji’s “Breezy Meadows” letter. But his stay in Salem was more extended and active than this brief reference indicates. Recently we have been fortunate enough to find out more about it. The steps leading to this discovery are perhaps of interest.

“He is a blazing, roaring fire consuming all impurities to ashes.”

Ramakrishna speaking of Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda in America – New Discoveries

I have a message to the West as Buddha had a message to the East

Swami Vivekananda

1958

1958