“We may venture to affirm, that, on attentive inquiry, we shall find in the Puranas, and other fabulous writings of the Hindus, almost the whole mythology of the Greeks and Romans. Some particulars may be modified, and heroes in both of the latter countires may be found, who have been transmored into demi-gods;

but all the principal features of the system may be traced.” – Edinburg Review, No. 29.

Philostratus (179-250 AD – “The Athenian” Greek sophist) makes Pythagoras (570 – 495 BC) say to Thespesion,

when reproaching him for his partiality to the Egyptians: “Admirer as you are of the philosophy which the Indians

invented, why do you not attribute it to tis real parents, rather than to those who are only so by adoption”

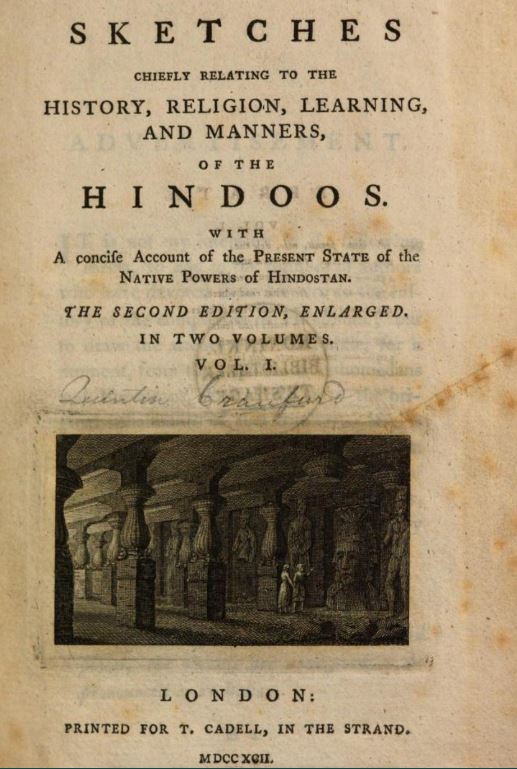

Sketch – Chapter X –

Learning and Philosophy of the Brahmans – p. 252

Q. Craufurd

p. 254

Strabo informs us (Strabo, 15. Porphyr.) , that they (Indian philosophers) cultivated natural philosophy and astronomy.

They were held in so high repute for their maxims of morality and for their knowledge in science and philosophy, that, besides Pythagoras, many went from Greece and other more eastern countries, purposely to be instructed by them.

Such were:

Democrites the Abderian

Pyrrhon

Bardesanes of Bablyon, who lived in the time of Alexander Serverus, is said to have converted with the Brachmanes (Brahmans) whom he represented as chiefly occupied with the adoration of God, and the duties of morality.

===========

Philostratus’ Life of Apollonius:

Chapter 6

Next day a discussion is held with the gymnosophists, who are lead by Thespesion (6.10-14). The latter defends the unpretentious philosophy and life-style of the gymnosophists; Apollonius replies with a speech justifying his choice of Pythagoreanism and emphasizing the priority and superiority of Indian wisdom in relation to that of the gymnosophists.

Iarchus, the Hindu philosopher, likewise says to Apollonius of Tyana (Charismatic teacher and miracle worker 1Cent CE – Journey to India – stayed with Indian philosopher King Phraotes who tells Apollonius about the place where the Indian sages live) , who asked his opinion concerning the soul” We think of it what Pythagoras taught you, and what we taught the Egyptians.”

Lucian, when making Philosophy complain to Jupiter, of some who had dishonored by her by their conduct, supposes the Indians to have been the first who received her amongst them: “I went amongst the Indians, and made them come down from their elephants and converse with me. From them I went to the Ethiopians and then came to the Egyptians.”

p. 171

The four Yugs, or ages of the Hindus, bear so marked an affinity to those of the Greeks and Romans, as we conceive leaves but little doubt of their origin.

p. 171-172

AND

On Egypt and other Countries

by Lieutenant Francis Wiford

From the Ancient books of the Hindus

on page 296

The Mythology of the Hindus is often inconsistent and contradictory; and the same tale is related in many different ways: Their Physiology, Astronomy, and History are involved in allegories and enigmas, which cannot but see extravagant….

So striking, in my appreciation, is the similarity between several Hindu legends, and numerous passages in Greek authors concerning the Nile and the countries on its borders, that, in order to evince their identity, or at lease their affinity, little more is requisite than barely to exhibit a comparative view of them. The Hindus have no ancient civil history; no had the Egyptians any work purely historical’ but there is abundant reason to believe that the Hindus have preserved the religious fables of Egypt, though we cannot yet positively say, by what means the Brahmens acquired a knowledge of them: it appears, indeed, that a free communication formerly subsisted between Egypt and India; since Ptolemy acknowledges himself indebted for much information to many learned Indians, whom he had seen at Alexandria; and Lucian informs us, that pilgrims from India reported to Hierapolis in Syria; which place is called in the Puranas, at least as it appears to me, Mahabhaga, or the station of the goddess Devi with that epithet; even to this day the Hindus occasionally visit, as I am assured, the two Jwala-muchis, or Springs of Naphtha in Cush-dwipa within, the first of which, dedicated to the same goddess with the epithet Anayasa, is not far from the Tigris; and Strabo mentions a temple, on that very spot, inscribed to the goddess Anaias.

p. 297

……

on. 353 – From the Ancient books of the Hindus.

The emigration of the Cutila-cefas from Inida to Egypt is mentioned likewise by Philostratus in his life of Apollonius. When the singular man visited the Brahmens, who lived on the hills, to the north of Sri-nagara, at a place now called Triloci-narayana near the banks of the Cedara-ganga, the Chief Brahment, whom he calls IARCHAS, gave him the following relation concerning the origins of the Ethiopians: “They resided, said he, formerly in this country, under the dominion of a king, named Ganges; during whose reign the Gods took particular care of them….”

Researches Concerning the Laws, Theology, Learning, Commerce, Etc.

of Ancient and Modern India

by Q. Craufurd, Esq.

in Two Volumes

Vol I

London

1817

=

Philostratus’ Life of Apollonius:

Apollonius was a third-century biography of a charismatic teacher and miracle worker from the first century CE, who is often likened to Jesus of Nazareth.

Book 3 (Philostratus, Life of Apollonius)

Book 3 is almost entirely devoted to Apollonius’ journey to and stay with the Indian sages. The travelers pass a mountain where pepper trees grow, and reach the Ganges plain (3.5), where they witness a sensational snake hunt (3.6-8). Four days later they reach the castle of the sages (3.10). Apollonius is immediately invited to hold a discussion with the sages, while his fellow travelers are accommodated in a neighboring village (3.12). Chapters 13-15 deal with the castle and environs and with the life-style of the sages. During the first discussion (3.16-25), their leader Iarchas displays the prophetic gifts and explains that the sages regard themselves as gods because of their virtue (3.18). The conversation also ranges over reincarnation, Homeric and Indian heroes, justice, and the Indian cult of Tantalus. It is interrupted by the arrival of an Indian king (3.26f), who proves to be inferior to Phraotes because of his complete lack of interest in philosophy (3.28) and his antipathy to everything Greek (3.31). Apollonius manages to cure him of this antipathy, but refuses to accept an invitation from the king (3.32f).

In a second discussion involving Apollonius and the sages (3.34-37), to which Damis is also invited, they discuss views of the cosmos and other questions. The sages perform a number of acts of healing (3.38-40). Later private discussions between Iarchas and Apollonius concern astrology and cultic practices; Apollonius’ writings on these topics are supposed to be the result of these conversations (3.41). The wonders of nature in India also come up for discussion (3.45-49). After staying with the sages for four months, Apollonius and his companions begin the return journey (3.50). Book 3 concludes with their return via the Persian Gulf, Babylon and Antioch to Ionia (3.51-58).

More:

https://www.livius.org/sources/about/philostratus-life-of-apollonius/

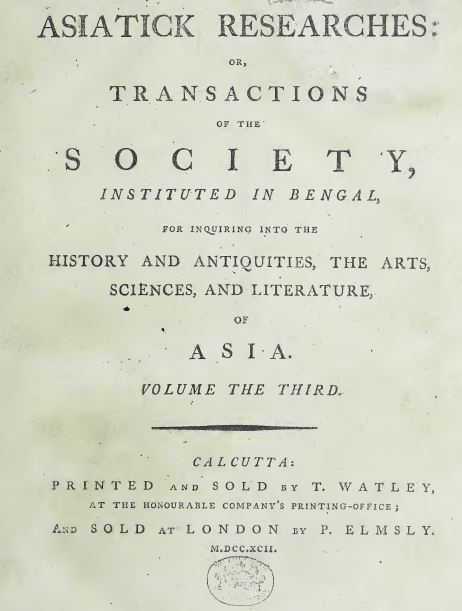

Asiatick Researches:

or,

Transactions

of the

Society,

Instituted in Bengal,

for inquiring into the

Hisotry and antiquities, The Arts,

Sciences, and Literature,

of

Asia

Volume The Third

M DCC XCII (1792)

XIII

On Egypt and other Countries

by Lieutenant Francis Wiford

From the Ancient books of the Hindus

p. 295-6

So striking, in my apprehension, is the familiarity between serval Hindu legends and numerous passages in Greek authors concerning the Nile and the countries on its borders that, in order to evince their identity or at least the affinity, little more is requisite than barely to exhibit a comparative view of them. The Hindus have not ancient civil history; nor had the Egyptians any work purely historical; but there is abundant reason to believe that the Hindus have preserved the religious fables of Egypt, though we cannot positively say by what means the Brahmins acquired a knowledge of them: it appears, indeed, that a free communication formerly subsisted between Egypt and India; since Ptolemy acknowledges himself indebted for much information to many learned Indians, whom he had seen in Alexandria; and Lucian informs us, that pilgrims from India resorted to Hierapolis in Syria; which place is call in the Puranas, at least as it appears to me, Mahabhaga, or the station of the goddess Devi with that epithet; even to this day the Hindus occasionally visit, as I am assured, the two Jwala0muchis, or Sprints of Naphtha in Cusha-dwipa within, the first of which, dedicated to the fame goddess with the epithet Anayasa, is not far from the Tigris,’ and Strabo mentions a temple, on the very spot, inscribed to the goddess Anaias.